In a nutshell

There is a good chance that low oil prices could stay with us for some time, if not indefinitely.

As oil revenues dry up, there will be a need to raise other forms of revenues, as well as to rationalise the non-oil economy by making it more productive and efficient.

A refocus on industrialisation and manufacturing is easier said than done, but one option is to invite in multinational companies.

Are the low oil prices that we’ve seen since 2014 likely to persist? If so, in the absence of massive oil revenues, how should the governments of oil-producing economies adjust their fiscal policies? And what new industries should be encouraged to generate income and wealth? These are critical issues with which the MENA region must grapple in the coming years and decades.

Is the low oil price permanent?

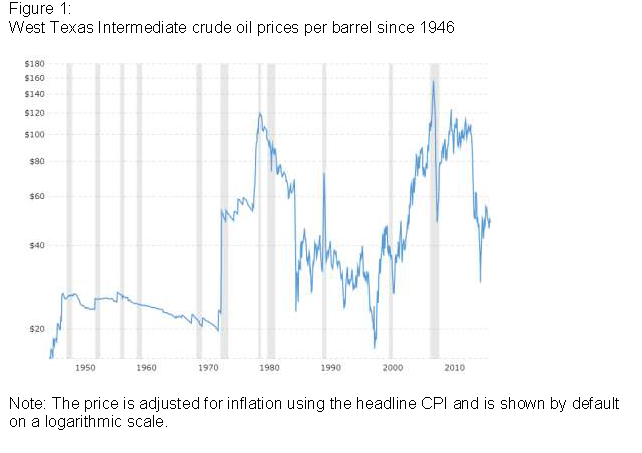

There is a good chance that low oil prices – in the range of $45 to $55 per barrel – could stay with us for some time, if not indefinitely. It is not that extended periods of low oil prices have not been seen before – for example, between June 1980 and April 1986 (see Figure 1). But that drop was caused primarily by a cyclical slack in demand, which was therefore reversible and which did in fact reverse when the recession ended.

This time may be different. The new extraction technology has allowed the Bakken oil fields in the United States to operate at far lower start-up costs than was the case in traditional oil fields. The new drilling technologies have been estimated to have increased the world’s petroleum supplies six-fold. As has always been true in the history of industrial revolutions, new technologies are often game changers.

Describing the new world of low oil prices, a recent column in the Harvard Business Review says that ‘The current low oil price environment is not an “oil bust” that will be followed by an “oil boom” in the near future. Instead, it looks as if we have entered a new normal of lower oil prices that will impact not just oil and gas producers but also every nation, company, and person depending on it.’ (Hartmann and Sam, 2016).

The breakeven point is about $50 for the new shale oil technology. Add to this the much more flexible supply response of new oil technology: one recent study finds that the output elasticity of unconventional new wells to price changes is three to four times that of conventional wells (Bjørnland et al, 2016). This combination produces a floor for oil prices from which it may be hard to escape.

How should oil-producing economies adjust?

Sovereign funds, where they exist, are falling fast. Saudi Arabia’s fund has dropped from over a trillion dollars a few years ago to only $514 billion today. Other Gulf states are in similar shape. These revenues may dry up soon and there will be a need to raise other forms of revenues, as well as to rationalise the non-oil economy by making it more productive and efficient.

As for the first task, raising more revenue, arguably the best vehicle may be to improve income tax collection:

- First, income tax is generally less regressive than value added tax, especially if it is designed to be progressive.

- Second, income tax does not distort production.

- Third, income tax has the indirect social benefit of making bureaucracies more transparent if governments must solicit more taxes from their citizens (Mohtadi et al, 2017). Some have argued that the government’s need for direct taxation was the source of greater political accountability in nineteenth century Europe (North, 1990; Hoffman and Norberg, 1994). In contemporary societies, this argument has been extended by Ross (2004), Brautigam et al (2008) and McGuirk (2013).

- Finally, citizens are likely to become more involved in their governance if they have to pay taxes. This line of reasoning has been used to argue that distributing oil revenues to the citizens and then taxing them creates a sense of ownership that makes them scrutinise their governments more closely (Devarajan et al, 2011).

Increasing the size of the non-oil pie

The second task is how to generate wealth by making the non-oil economy more productive and efficient. This brings us to industrial and trade policies. There is ample evidence that MENA oil producers lag in industrial performance compared with their resource-poor counterparts.

Referring to a United Nations report, one study shows that of the ‘six components of industrial performance: manufacturing valued added (MVA) per capita; manufactured exports per capita; share of MVA in GDP; share of medium/high technology production in MVA; share of medium/high technology exports in manufactured exports; and share of manufactured exports in total exports, MENA underperformed in first five indicators both Latin America and the Caribbean, and East Asia and the Pacific regions’ (Elbadawi and Gelb, 2010). As for the last indicator, the share of manufactured exports in total exports, the MENA underperformed all other developing regions.

But a refocus on industrialisation and manufacturing is easier said than done. It faces numerous challenges, ranging from competition from low labour cost producers to development of the necessary skills and supportive public policies (such as selective subsidies).

One option is to invite in multinational companies. This is a politically sensitive topic for many. But with proper regulation, including domestic content requirements, and a policy focus on technical skill development, improvements in financial and property rights institutions, and greater policy transparency, such policies are likely to bear fruit, as the Asian example suggests.

It is time to think about the next chapter in the MENA region’s development history – the post-oil chapter.

Further reading

Bjørnland, H, F Nordvik and M Rohrer (2016) ‘How Flexible is US Shale Oil Production? Evidence from North Dakota’, paper presented at USC Conference on Oil and Middle East Economies.

Brautigam, D, O Fjeldstad and M Moore (eds) (2008) Taxation and State-Building in Developing Countries: Capacity and Consent, Cambridge University Press.

Devarajan, S, H Ehrhart, Tuan Minh Le and Raballand (2011) ‘Direct Redistribution, Taxation, and Accountability in Oil-Rich Economies: A Proposal’, Center for Global Development Working Paper No. 281.

Elbadawi, I, and A Gelb (2010) ‘Oil, Economic Diversification and Development in the Arab World’, ERF Policy Research Report 35.

Hartmann, B, and S Sam (2016) ‘What Low Oil Prices Really Mean’, Harvard Business Review, 28 March.

Hoffman, PT, and K Norberg (eds) (1994) Fiscal Crises, Liberty, and Representative Government 1450-1789, Stanford University Press.

McGuirk, E (2013) ‘The Illusory Leader: Natural Resources, Taxation, and Accountability’, Public Choice.

Mohtadi, H, M Ross, S Ruediger and U Jarrett (2017) ‘Does Oil Hinder Transparency?’ UCLA and University of Wisconsin Working Papers.

North, D (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press.

Ross, M (2004) ‘Does Taxation Lead to Representation?’, British Journal of Political Science.