In a nutshell

As of 2016, 75% of Syrian refugees in Jordan did not have health insurance.

Syrians have high rates of food insecurity, particularly in refugee camps.

Policy-makers need to take action to improve access to health insurance and food security for this vulnerable population; without action, Syrians will be at increased risk of suffering, illness and shortened lifespans.

Among the 1.3 million Syrian refugees in Jordan, struggles with health and hunger may endanger an already vulnerable population. The latest evidence indicates that their health and wellbeing are at risk and need additional support.

We know that food insecurity not only harms human health but also hinders economic growth (Barrett, 2002). Likewise, access to healthcare is not only critical for human development but it is a fundamental human right. When refugees lack health insurance or struggle with food security, this puts an already vulnerable population further at risk and limits their potential and development.

Policies in Jordan for refugees’ healthcare and food security

Before receiving most health and food services, Syrian refugees in Jordan must register officially with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (Salemi et al, 2018). Once they have registered with the UNHCR, they can apply for a Ministry of Interior (MOI) service card.

This service card allows refugees to access Jordanian public health facilities. Initially, care was free for refugees, then at a subsidised cost, paying the same rate as uninsured Jordanians, but as of January 2018, that subsidy has ended (Amnesty International 2016; Dupire 2018). This cost is likely to be a barrier for refugees (Doocy et al, 2016). Refugees without an MOI card face difficulty accessing care (Amnesty International, 2016; Norwegian Refugee Council, 2016).

Likewise, it is only after registration and with an MOI card that refugees can potentially receive food aid from most sources, including the World Food Programme (WFP).

The WFP also screens refugees for eligibility, based on need, before they can receive food support (World Food Programme, 2015, 2016). For example, to be eligible, a family’s per capita expenditure per month needs to be under 68 Jordanian dinars, or they must have other ‘vulnerable characteristics’, such as being in a camp or a household that is at least two thirds children.

Few Syrian refugees have health insurance

Health insurance is not readily accessible for Syrian refugees in Jordan. Lack of health insurance may be a barrier to receiving care as well as increasing the financial challenges of paying for care.

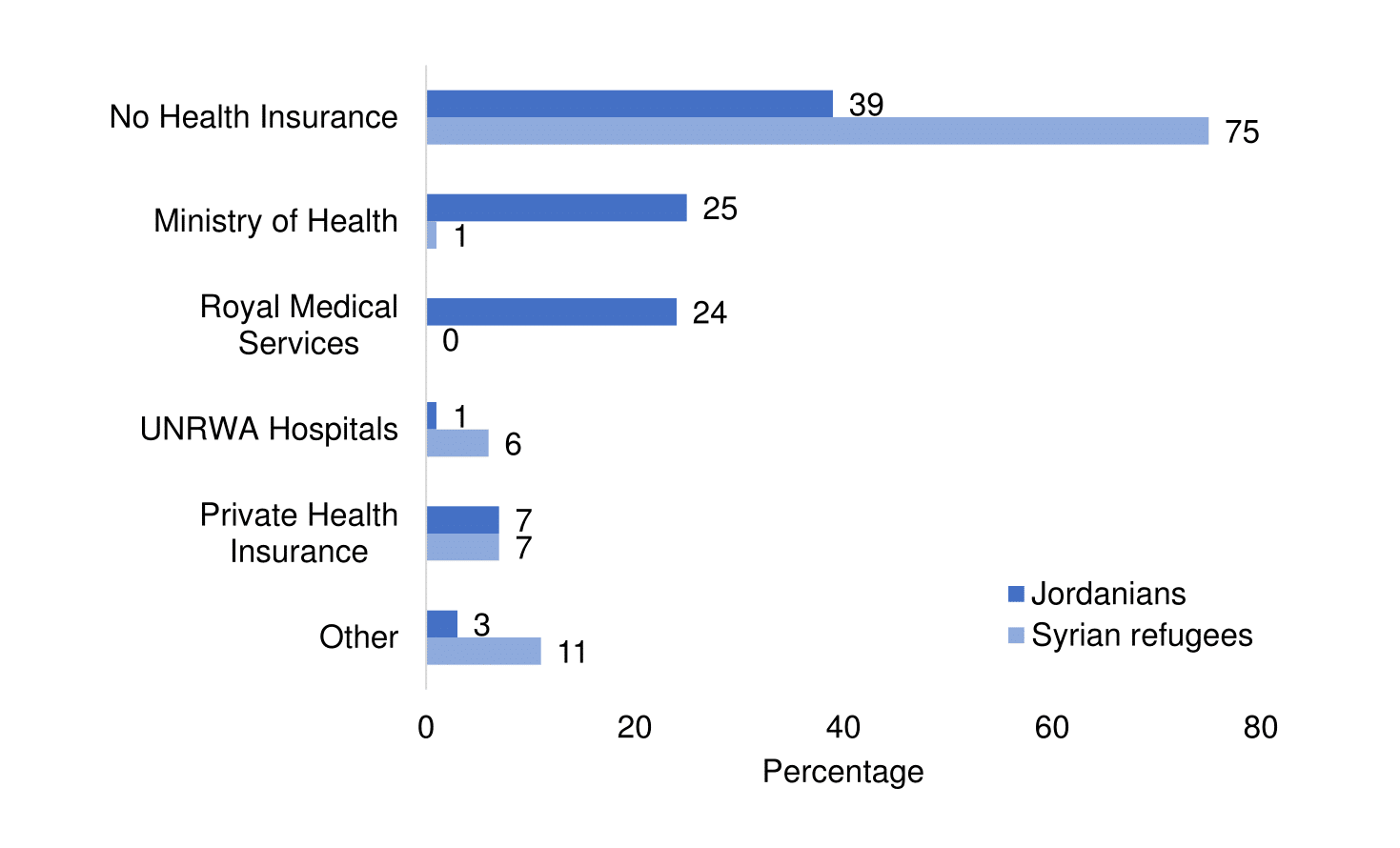

The majority (75%) of Syrian refugees in Jordan do not have any form of health insurance coverage (Figure 1), according to the 2016 Jordan Labor Market Panel Survey (JLMPS). In contrast, the majority of Jordanian citizens have insurance and only a low percentage (39%) of Jordanians are not insured. Among Syrian refugees, cost is a major barrier to seeking care (Doocy et al, 2016), and those without insurance will face higher out of pocket costs.

Figure 1:

Health insurance (percentage), Jordanians and Syrian refugees aged 6+, 2016

Source: Krafft et al, 2018

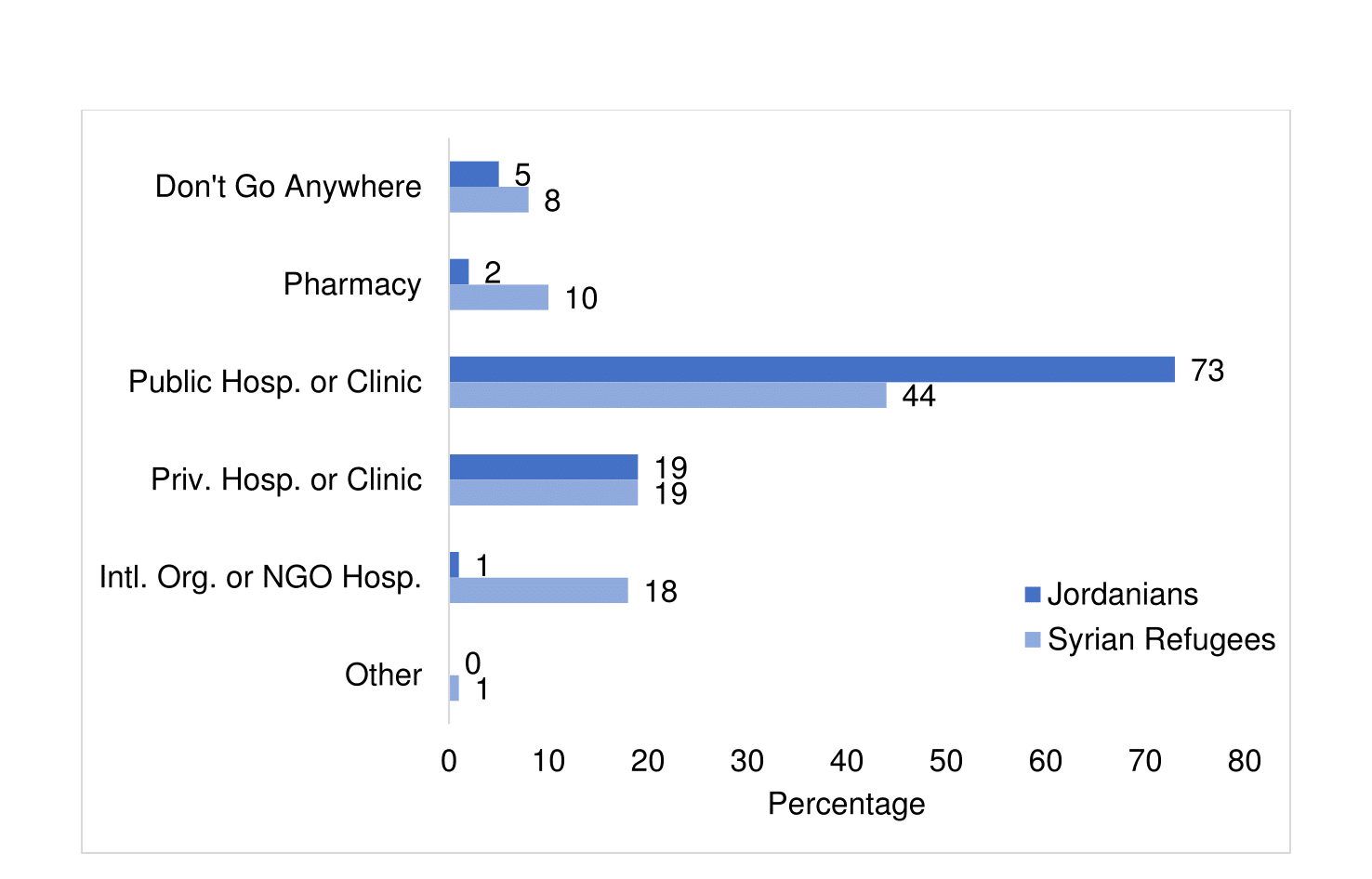

As a result of low insurance coverage and cost barriers in public facilities, Syrians rely more on charity care, pharmacies or forgoing care when ill. While, as of 2016, 73% of Jordanians report that they go to public hospitals or clinics when they need care, only 44% of Syrians do so. Refugees use private hospitals and clinics at a similar rate as Jordanians (19%) and are likely to pay high costs of care as a result (Doocy et al, 2016).

There are more Syrians who report not going anywhere when sick (8%) than Jordanians (5%). Syrian refugees are more likely to use pharmacies (10%) than Jordanians (2%), which are likely to offer a more limited range of services than clinical facilities. Another key source of care for Syrian refugees are international organisations and NGO facilities (18%).

Figure 2:

Healthcare source (percentage), Jordanians and Syrian refugees aged 6+, 2016

Source: Krafft et al, 2018

Syrian refugees struggle with food security

Although the WFP and other organisations assist Syrian refugees, many still struggle with food insecurity. While some refugees are registered with ration cards and receive food vouchers, others may not receive food assistance.

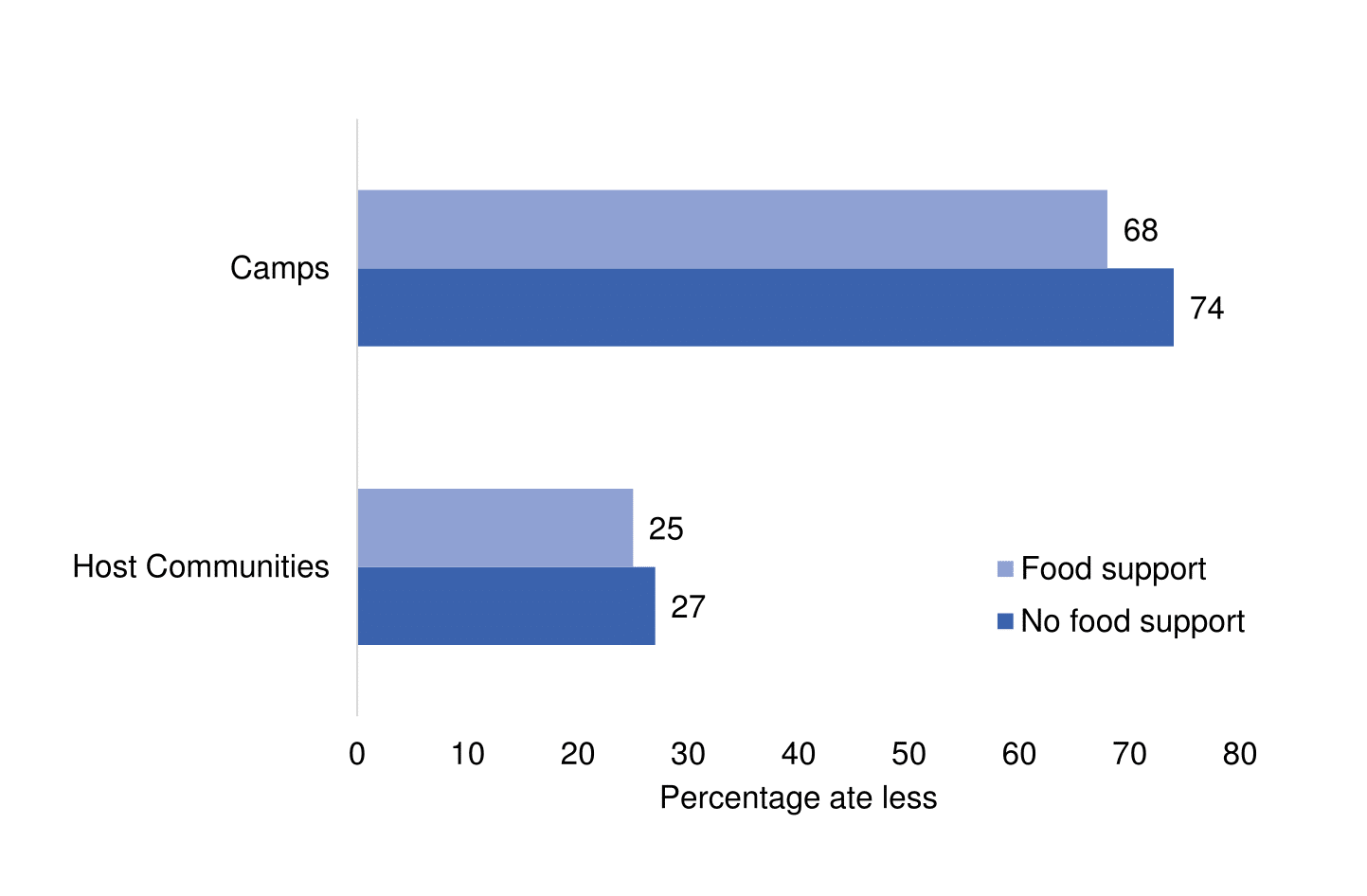

We consider Syrian refugees who report eating less in the last 12 months due to scarcity of food to be food insecure (See Krafft et al, 2018, for a detailed investigation of different measures of food security). Even when they have food support, there is substantial food insecurity among Syrians.

Food insecurity is high in host communities and especially refugee camps. Figure 3 shows the percentage of Syrian refugees aged 15-59 who ate less by whether they received food support (food vouchers or ration cards). The refugees that are the most food insecure (74%) are the Syrians with no food support in camps.

Among Syrians with food support, Syrians in the camps have the highest rate of food insecurity (68%). In host communities, rates of food insecurity are lower (25% with food support, 27% without), but still concerning. While food support is reducing food insecurity, it is not preventing food insecurity. The additional purchasing and livelihoods opportunities outside the camps appear to be important in reducing food insecurity.

Figure 3:

Food insecurity: ate less (percentage) by receipt of food support, Syrian refugees aged 15-59 in host communities versus camps, 2016

Source: Krafft et al, 2018

Reducing food insecurity and increasing health insurance coverage of refugees

Since the WFP is the primary programme battling hunger among the Syrians in Jordan, the funding of the WFP is critical for ensuring food security among refugees. Unfortunately, the WFP faces funding shortfalls, which has led to cuts in food support at times (Bellamy et al, 2017). As a result, even Syrian refugees who qualify for assistance are not receiving the support they need.

In addition, unlike other programmes that receive consistent funding, the WFP is funded by governments, companies and individuals on an entirely voluntary basis (World Food Programme, 2018). Finding more consistent and reliable funding for the WFP will help reduce hunger within the refugee population. The financing of food programmes, like the WFP, needs to be made a priority because food is a basic need for survival and critical for human development.

Improving Syrians’ access to healthcare in Jordan is important to protect refugees’ human rights and wellbeing. Syrians who have access to public health facilities may face unaffordable costs. These barriers limit Syrian refugees’ access to medical assistance.

Policy-makers must address the fact that the vast majority (75%) of the Syrian refugee population has no form of health insurance in Jordan and pays out of pocket for health services. Not having health insurance leaves a vulnerable population at high financial and health risk from health shocks.

Further reading

Amnesty International (2016) ‘Living on the Margins: Syrian Refugees in Jordan Struggle to Access Health Care’.

Barrett, Christopher (2002) ‘Food Security and Food Assistance Programs’, in Handbook of Agricultural Economics, edited by Bruce L. Gardner and Gordon C. Rausser.

Bellamy, Catherine, Simone Haysom, Cailtlin Wake and Veronique Barbelet (2017) ‘The Lives and Livelihoods of Syrian Refugees in Turkey and Jordan: A Study of Refugee Perspectives and their Institutional Environment in Turkey and Jordan’, Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute.

Doocy, Shannon, Emily Lyles, Laila Akhu-Zaheya, Ann Burton and Gilbert Burnham (2016) ‘Health Service Access and Utilization among Syrian Refugees in Jordan’, International Journal for Equity in Health 15(108): 1-15.

Dupire, Camille (2018) ‘Regularisation Campaign for Syrian Refugees Raises Healthcare Access Concerns’, The Jordan Times (April 2).

Krafft, Caroline, Maia Sieverding, Colette Salemi and Caitlyn Keo (2018) ‘Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Demographics, Livelihoods, Education, and Health’, ERF Working Paper No. 1184.

Norwegian Refugee Council (2016) ‘Securing Status: Syrian Refugees and the Documentation of Legal Status, Identity, and Family Relationships in Jordan’, Norwegian Refugee Council.

Salemi, Colette, Jay Bowman and Jennifer Compton (2018) ‘Services for Syrian Refugee Children and Youth in Jordan: Forced Displacement, Foreign Aid, and Vulnerability’, ERF Working Paper No. 1188.

World Food Programme (2015) ‘World Food Programme Beneficiary Targeting for Syrian Refugees in the Community,’ Al-Jubaiha, Rasheed District.

World Food Programme (2016) ‘WFP Jordan Situation Report # 13’.

World Food Programme (2018) ‘Funding and Donors‘.