In a nutshell

In all four countries, there are significant wealth gaps, especially across urban-rural and educated-uneducated divides, and between demographic groups.

There is evidence of increasing polarisation of wealth ownership in Egypt and Ethiopia, with the poorest 5% of households experiencing declining wealth.

Pre-existing wealth appears to play an important stand-alone role in households’ earnings, consumption and capacity for wealth accumulation.

Studies of the distribution of income and consumption expenditures have been finding modest degrees of inequality in the MENA region. But while the results are legitimate, their shortcoming is that income or consumption alone may not represent households’ living standards and economic inequality across households adequately.

- First, households derive benefits not only from new purchases, but also from their stock of possessions.

- Second, ownership of ‘productive assets’, such as means of transport and communication, affects households’ capabilities and incomes.

Wealth also influences households’ decisions over labour market participation and consumption smoothing over years – something that static evaluation of household incomes will not account for, and will be sensitive to. Since wealth is related positively to income, consumption and other capabilities, true economic inequality is likely to exceed inequality measured by income or consumption alone.

In a recent study (Hlasny and Al Azzawi, 2018), we re-examine economic inequality and mobility in three Middle East and North African countries (Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia) plus Ethiopia, by accounting explicitly for households’ stock of productive and non-productive assets, and relating them to their present and future earnings.

Our study relies on high-quality harmonised panel surveys to derive wealth indices based on productive and non-productive assets. To overcome the challenge of comparing wealth indices across countries and years, we benchmark the indices by applying the estimated asset prices in a base survey to other surveys. This allows us to infer differences in asset ownership across countries and years, and in Egypt and Ethiopia, it allows us to analyse changes in household wellbeing over time.

In all four countries, we find significant wealth gaps, especially across urban-rural and educated-uneducated divides. Wealth inequality across individual households also varies between demographic groups. Wealth is typically dispersed more unequally among rural households than among urban households, with the exception of Ethiopia and Tunisia, where the dispersion of wealth is higher in urban areas.

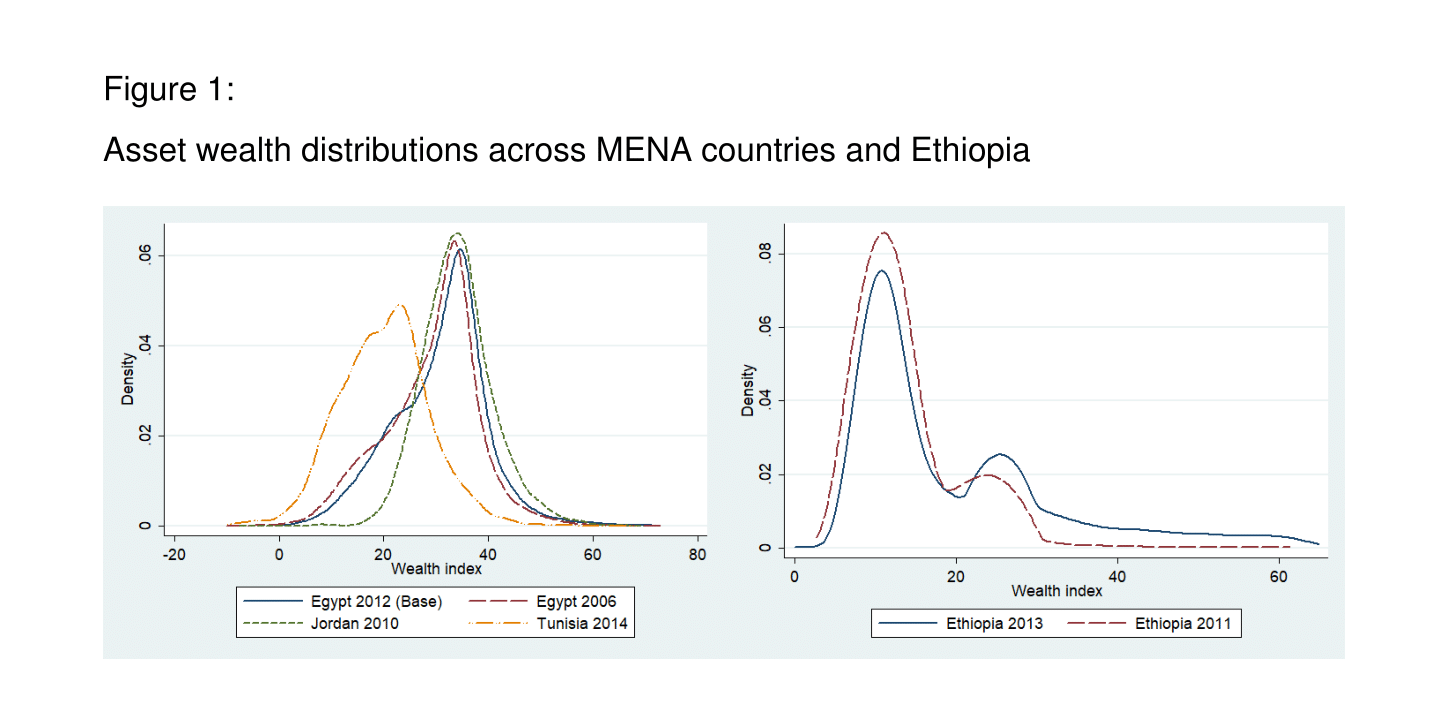

Wealth distributions also differ substantially across the four countries, both in their level and their shape (see Figure 1):

- In Egypt and Jordan, the distribution is fairly symmetric and bell-shaped without notable clusters of households in either tail.

- In Tunisia, the dispersion of wealth is wide around the centre and the distribution is bimodal, presumably because of polarisation between rural and urban households, but the tails are rather narrow.

- In Ethiopia, the distribution has a long right tail, suggesting that a small group of households have a substantially higher wealth than the vast bulk of the country’s population.

In Egypt and Ethiopia – for which we have multiple years of data – we find moderate improvements in asset ownership over time. Wealth rose for the majority of households in Egypt and Ethiopia, but the increases in wealth were modest. Few households changed their relative position over time.

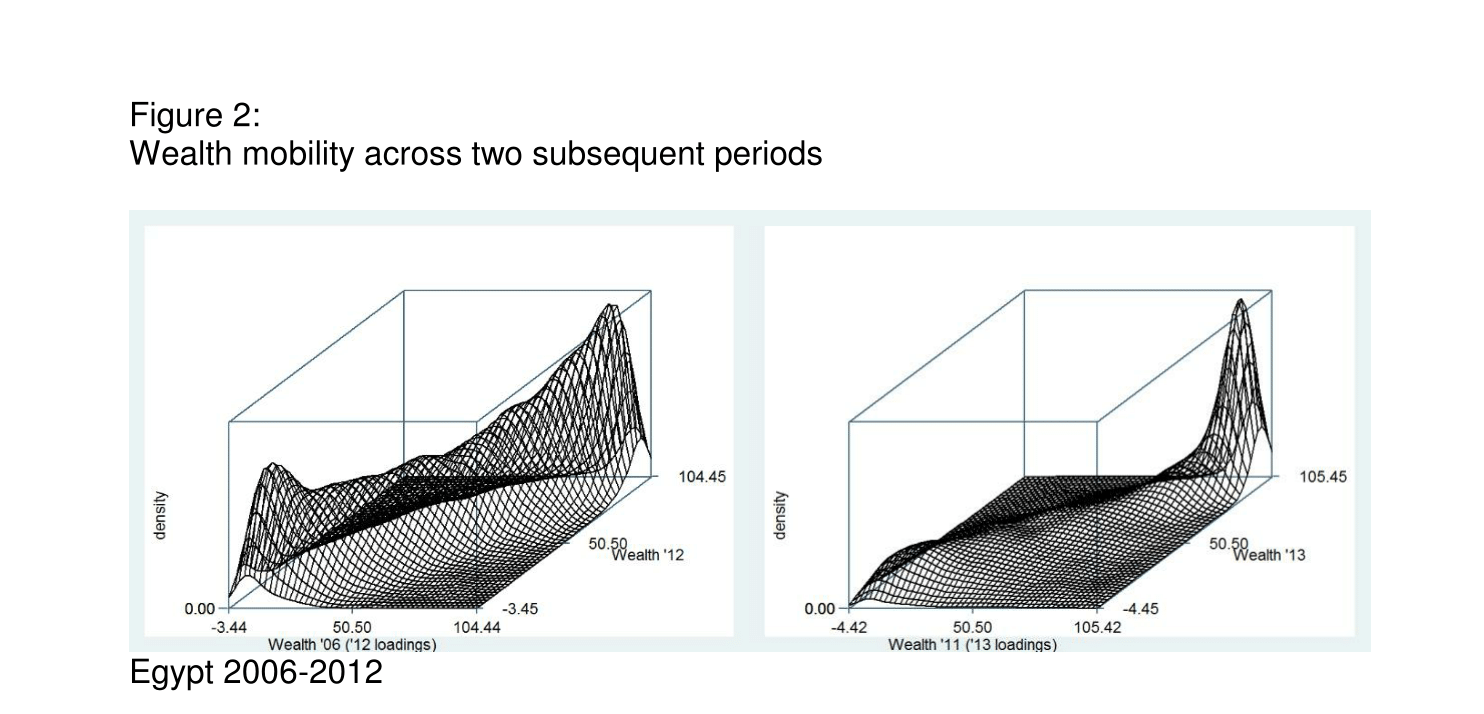

The association between past and current relative wealth was high in both countries, particularly among the wealthiest groups, indicating that middle-class households have a low prospect of rising to the top (see Figure 2).

More specifically, during the period from 1998 to 2012 in Egypt, growth in wealth favoured lower middle-class households, while in Ethiopia during the period from 2011 to 2013, growth was in favour of the richest 30% of households, whose wealth increased further in absolute terms.

In both countries, the poorest 5% of households have experienced declining wealth over the period we study. Combined with the trend among the wealthiest households, this provides some evidence of increasing polarisation of wealth ownership in the two countries.

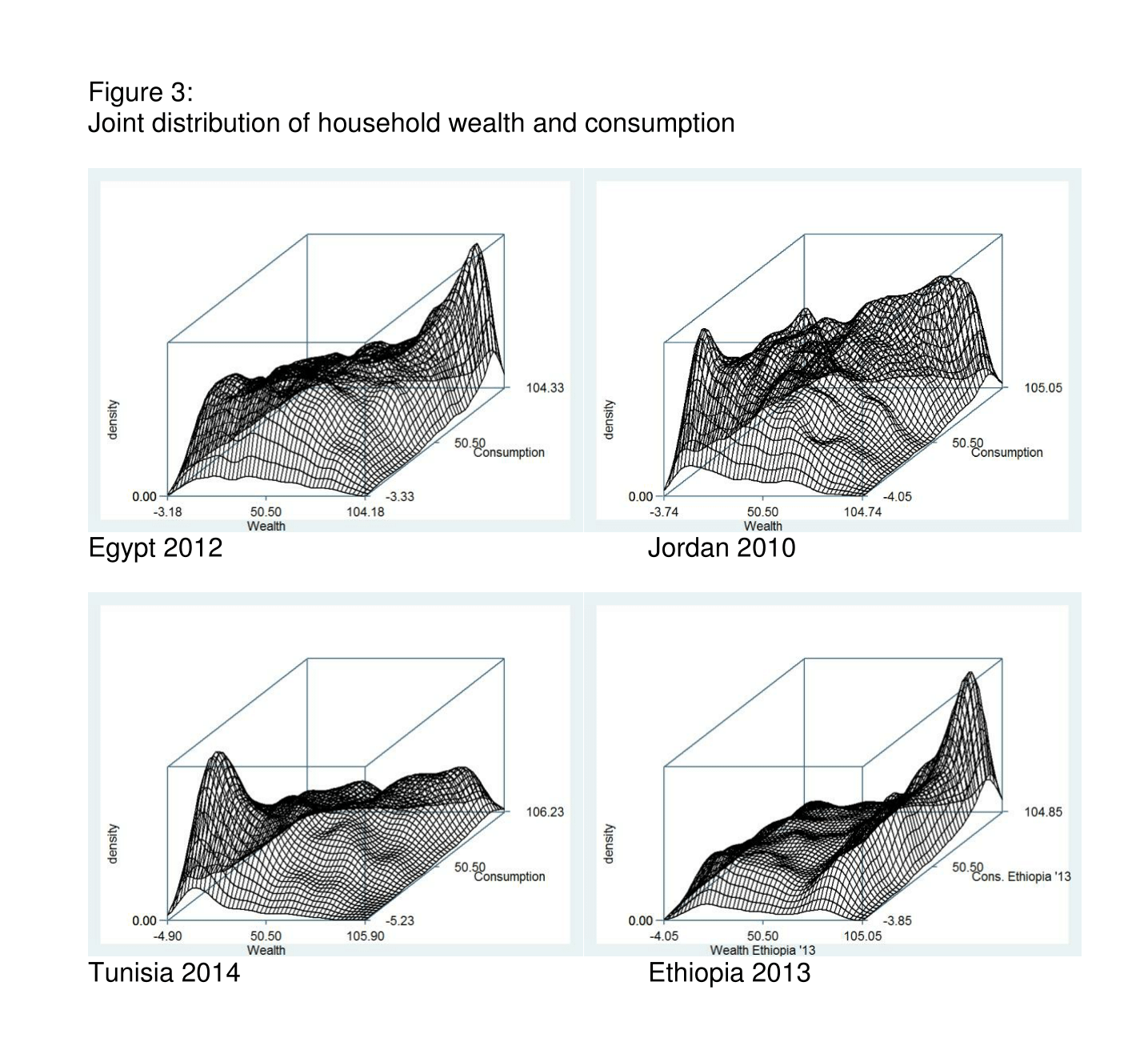

To understand the dynamics of wealth accumulation and mobility better, we juxtapose wealth distribution with the distribution of households’ earnings and consumption to gauge the degree of multidimensional inequality. We find that while households’ wealth and earnings are positively and highly correlated, they have different distributions and different trends over time. Their joint distributions also differ across the four countries (see Figure 3).

We also find that wealth accumulated in prior years is associated positively with households’ earnings, consumption and wealth retained in later years. Pre-existing wealth thus appears to play an important stand-alone role in households’ earnings, consumption and capacity for wealth accumulation.

Finally, juxtaposing households’ ownership of productive assets against that of non-productive assets, we find them to be substitutes bought by different households for different purposes, with different implications for households’ living standards and inequality across households. The relationship appears to be complex across low- and high-income households.

Productive assets appear to serve as essential resources supplementing low earnings in the MENA countries, but not as clearly in Ethiopia. In Ethiopia and Tunisia, moreover, higher-earnings households appear to invest substantially in productive assets. One possible interpretation is that in these latter countries, poorer households were financially restricted from obtaining adequate stocks of productive assets.

In sum, our study confirms that wealth plays an important role in the composite distribution of multidimensional wellbeing, households’ capabilities and inequality of opportunities. These results can help to inform policy options on how best, or whether at all, such inequality should be tackled. We hope that these initial results will inspire further investigation into the dynamic interplay of factors affecting multidimensional wellbeing and its distribution across households.

Further reading

Hlasny, Vladimir, and Shireen Al Azzawi (2018) ‘Asset Inequality in the MENA: The Missing Dimension?’, ERF Working Paper No. 1177.