In a nutshell

Technical and vocational education in Egypt is often associated with academic failure, rather than being an alternative path to productive and decent work.

Despite widespread unemployment among college graduates, tertiary education is still perceived as the ticket to some form of full-time employment opportunity.

It is essential to map the demand for and supply of skills in different economic sectors, including cognitive, technical and non-technical (social and behavioural) skills.

Egypt has a grand plan for the development of its system of technical education and a strong industrial sector that can compete globally. In June 2018, the Minister of Education and Technical Education signed a cooperation protocol with private firms to implement the ‘Egypt Makers’ initiative, under the slogan ‘Learn… Improve… Work’. The objective is to raise students’ production skills in general, and to advance TVE, which refers to all technical and vocational education and training at secondary level, generally comprising three-year programmes.

Starting in 2018-19, a new standard of evaluating students’ transition from high school to tertiary education will replace the existing traditional approach. The new system, more challenging and demanding for students, will use a ‘grade point average’ (GPA) system, which determines the final grade according to the average of a student’s grades throughout the three years of secondary education.

The facts

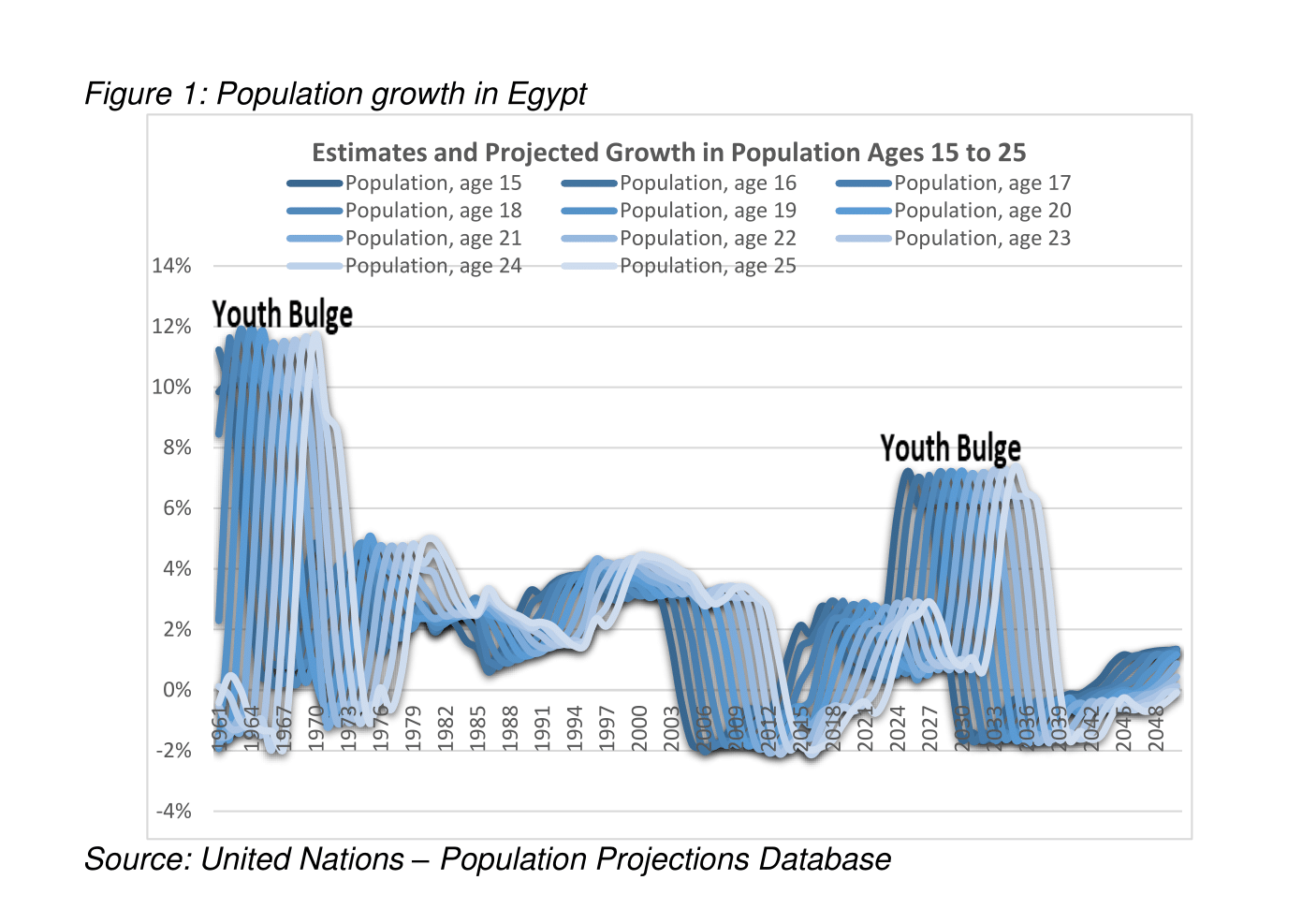

1- Egypt is facing another youth bulge soon. By 2030, Egypt’s working age population will have increased by 20%, putting the labour force at 80 million people (see Figure 1).

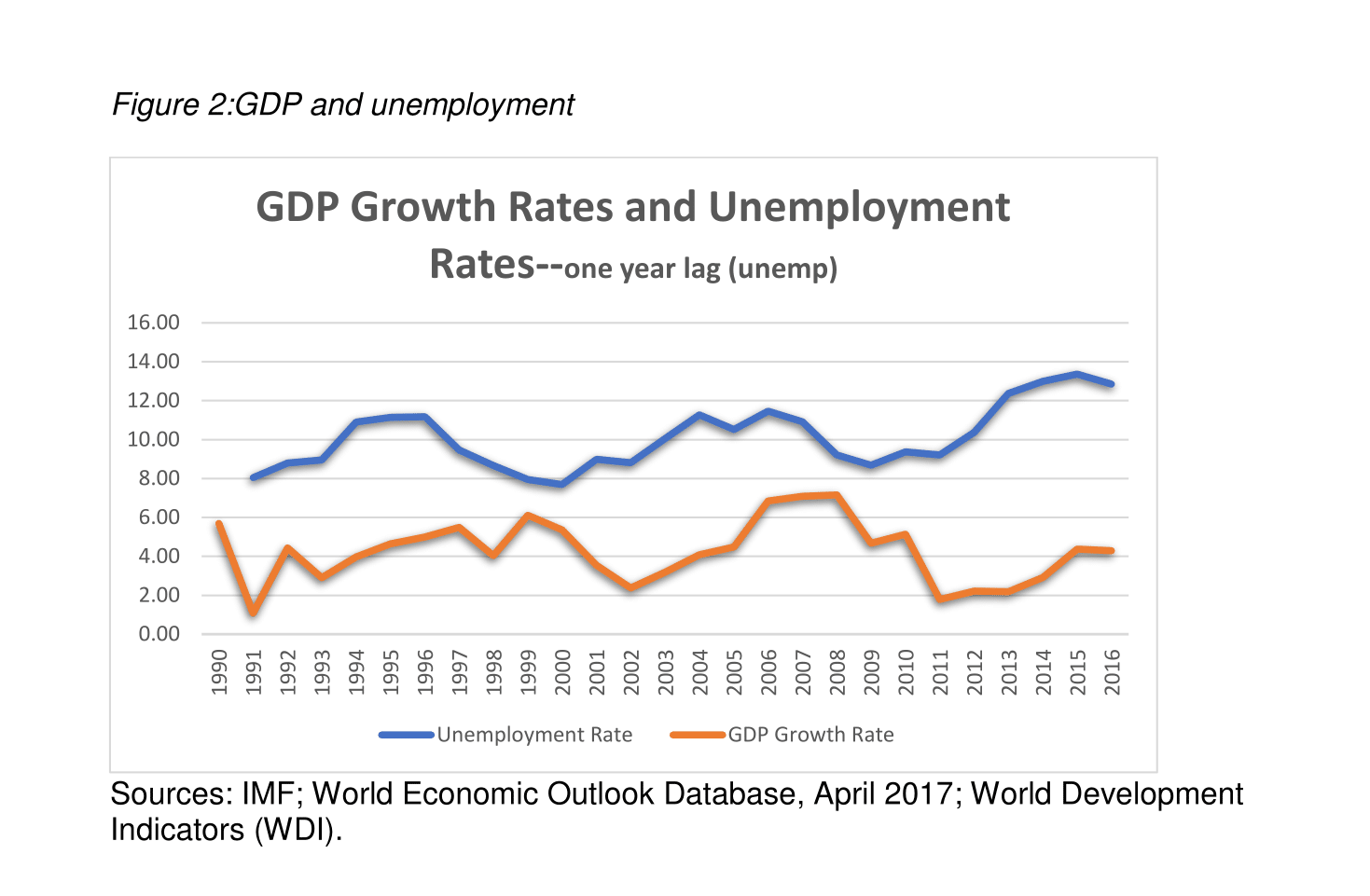

Despite reasonably good economic growth in the last few years, the unemployment rate in Egypt has been at record levels since 1990 (see Figure 2).

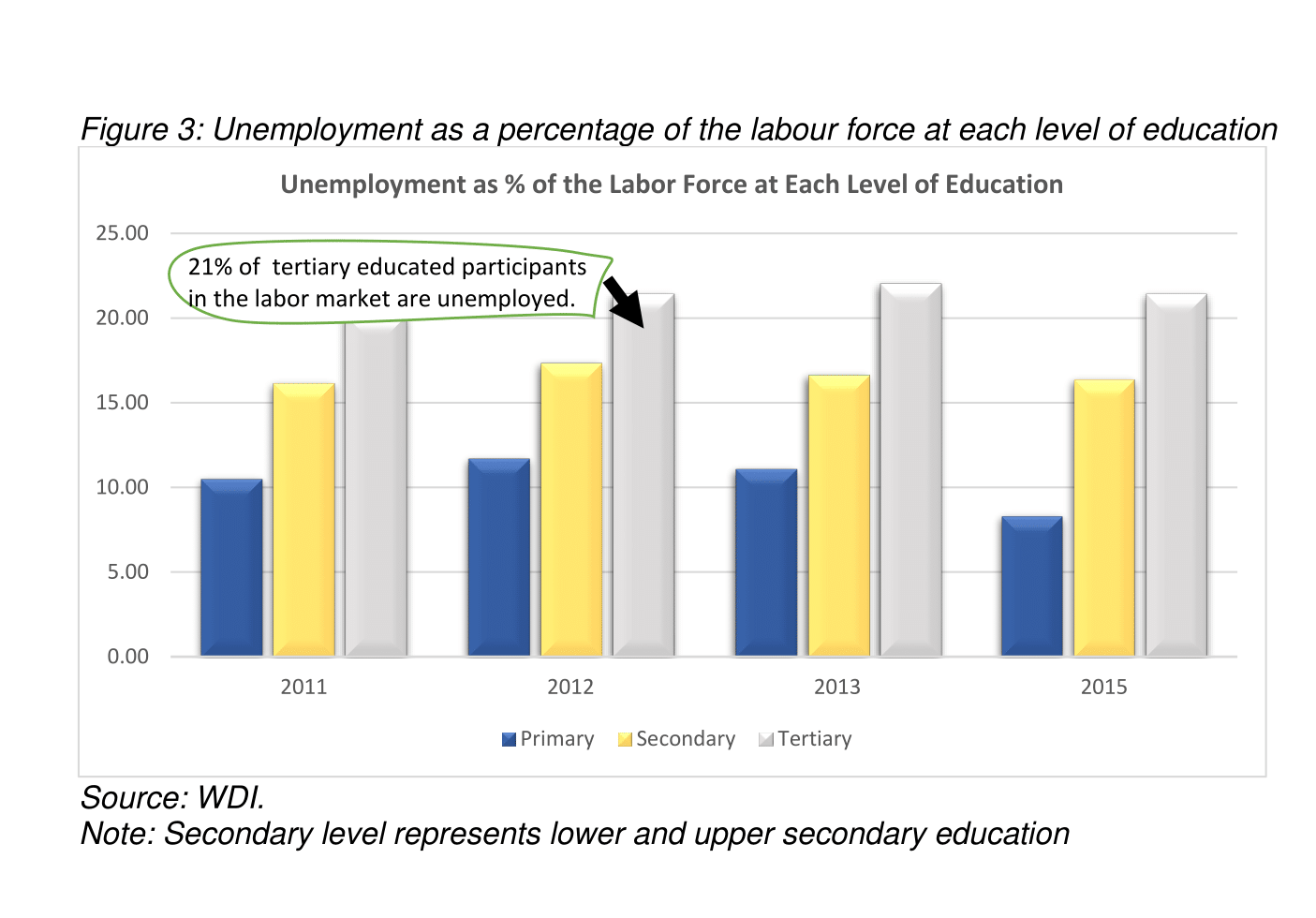

A closer look at unemployment rates shows a persistently negative relationship between unemployment rates and educational attainment. College graduates record the highest share of unemployment (see Figure 3).

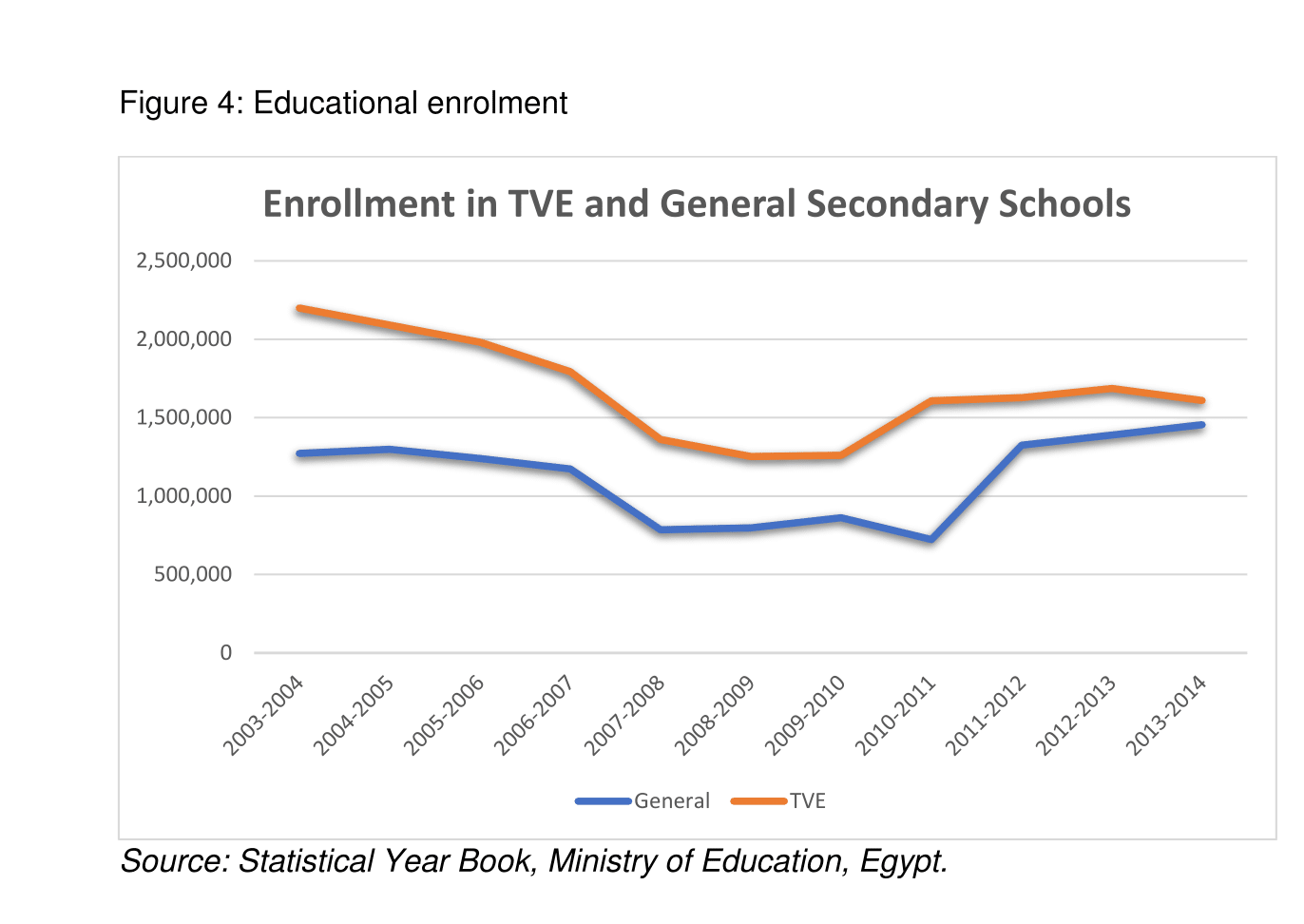

Yet enrolment in secondary general education, a pre-requisite for college admission, has been rising and is expected to rise in the future (see Figure 4).

2- In July 2017, Egypt’s Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics announced a rise in the number of foreign workers in Egypt by 1.1% from the previous year. These workers are mostly coming from Asia, in particular India and Bangladesh (36%).

3- A random search on the internet for ‘jobs in Egypt’ shows that 76% of the advertised vacancies are for candidates with technical experience.

4- The Global Talent Competitiveness Index ranks Egypt 104th out of 119 countries. In measures of the relevance of the education system to the economy, skills matching with secondary education, and skills matching with tertiary education, Egypt ranks 117th, 118th and 118th respectively.

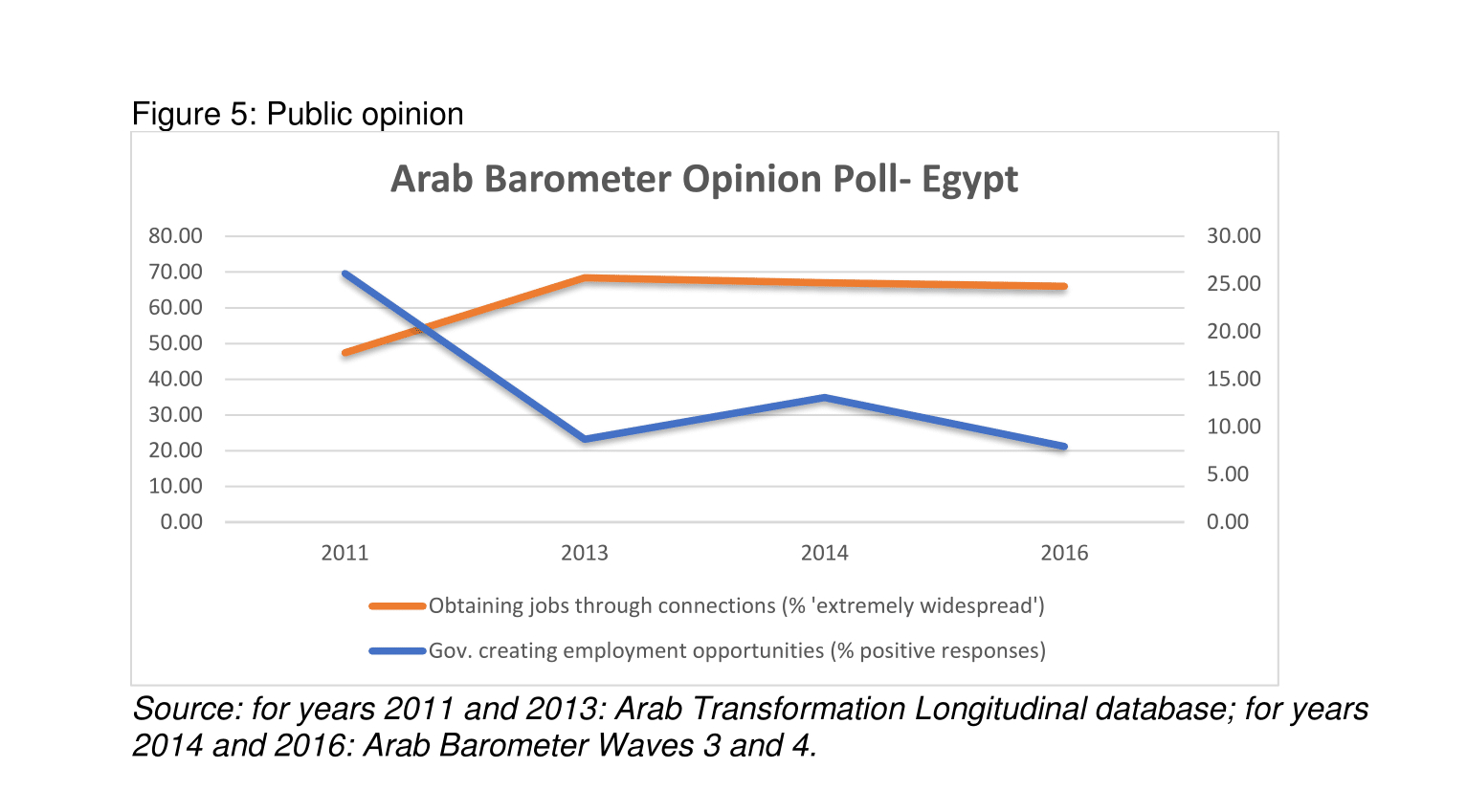

5- In addition to the pervasiveness of corruption, the public does not trust the government to be ‘doing a good job in creating jobs’, and the level of trust is in decline (see Figure 5).

The missing link

1- TVE is often associated with academic failure, rather than being an alternative path to productive and decent work. It is perceived as a ‘residual’, a last resort for academically low-performing students who are denied access to the general education that is a pre-requisite for college admission. This hierarchical structure is reflected in a ‘negative perception’ in cultural and social attitudes towards TVE.

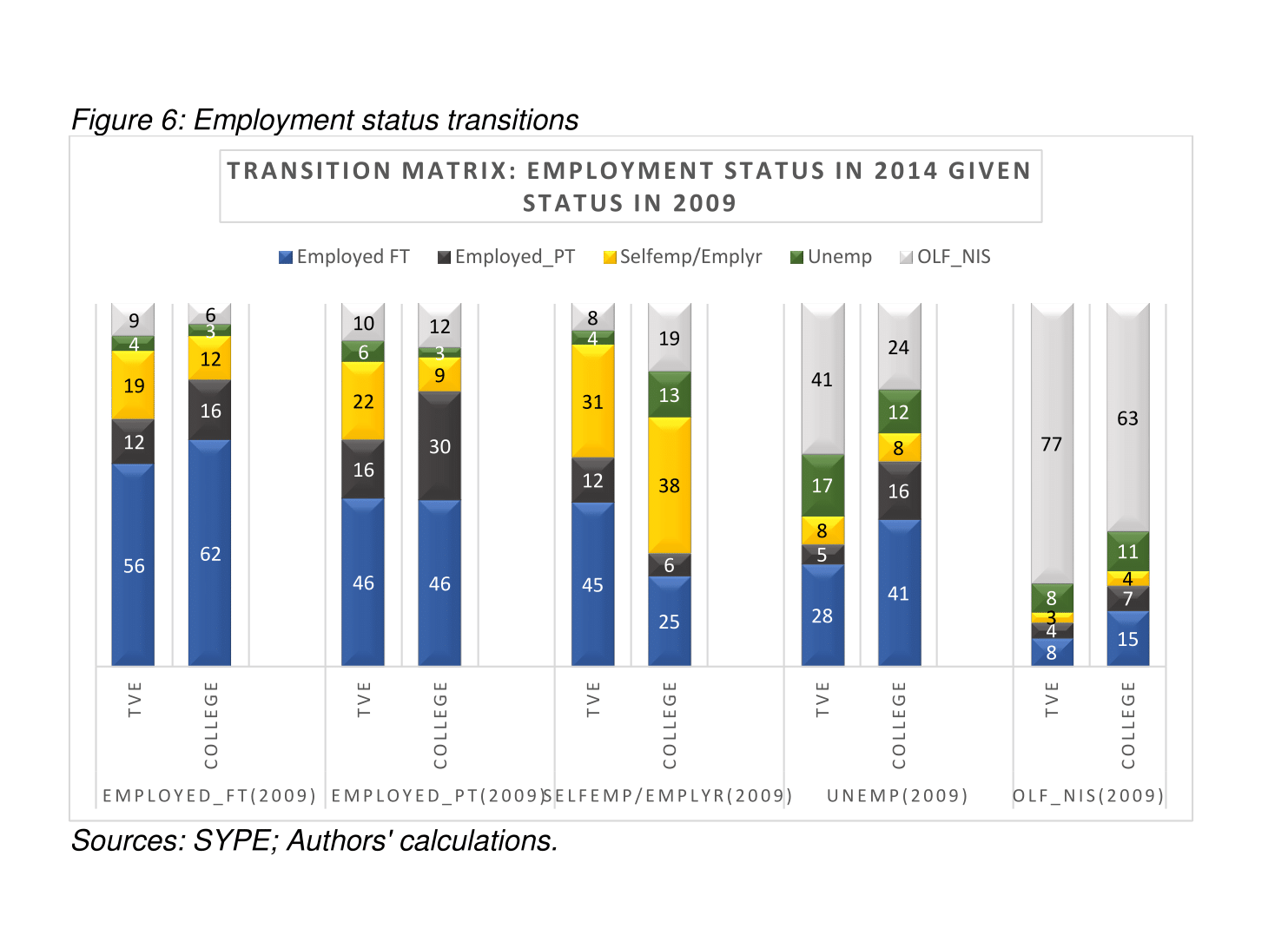

2- Despite widespread unemployment among college graduates (see Figure 3 above), tertiary education is still perceived as the ticket to some form of full-time employment opportunity. This is confirmed by analysis of data from the Survey of Young People in Egypt (SYPE), conducted in 2009 and 2014. Longitudinal panel analysis of labour market surveys confirms that college graduates are crowding out TVE graduates who are more likely to exit the labour force altogether (see Figure 6):

a. Each column in Figure 6 reflects the distribution of employment status in 2014 given the status in 2009. For example, unemployed college graduates in 2009 are twice as likely to move to full- or part-time jobs in 2014 compared with the unemployed TVE graduates. Indeed, unemployment for TVE graduates seems to be a precursor or a last resort before leaving the labour market all together. Close to 50% of the unemployed in the TVE group in 2009 end up leaving the labour market by 2014. This is twice the proportion of the unemployed college graduates who end up leaving the labour market in 2014. In addition, compared with TVE graduates, college graduates are more likely to join the labour market after few years out of the labour force. This is explained by earlier findings that marriage and childbearing responsibilities are limiting women’s opportunities in the labour market.

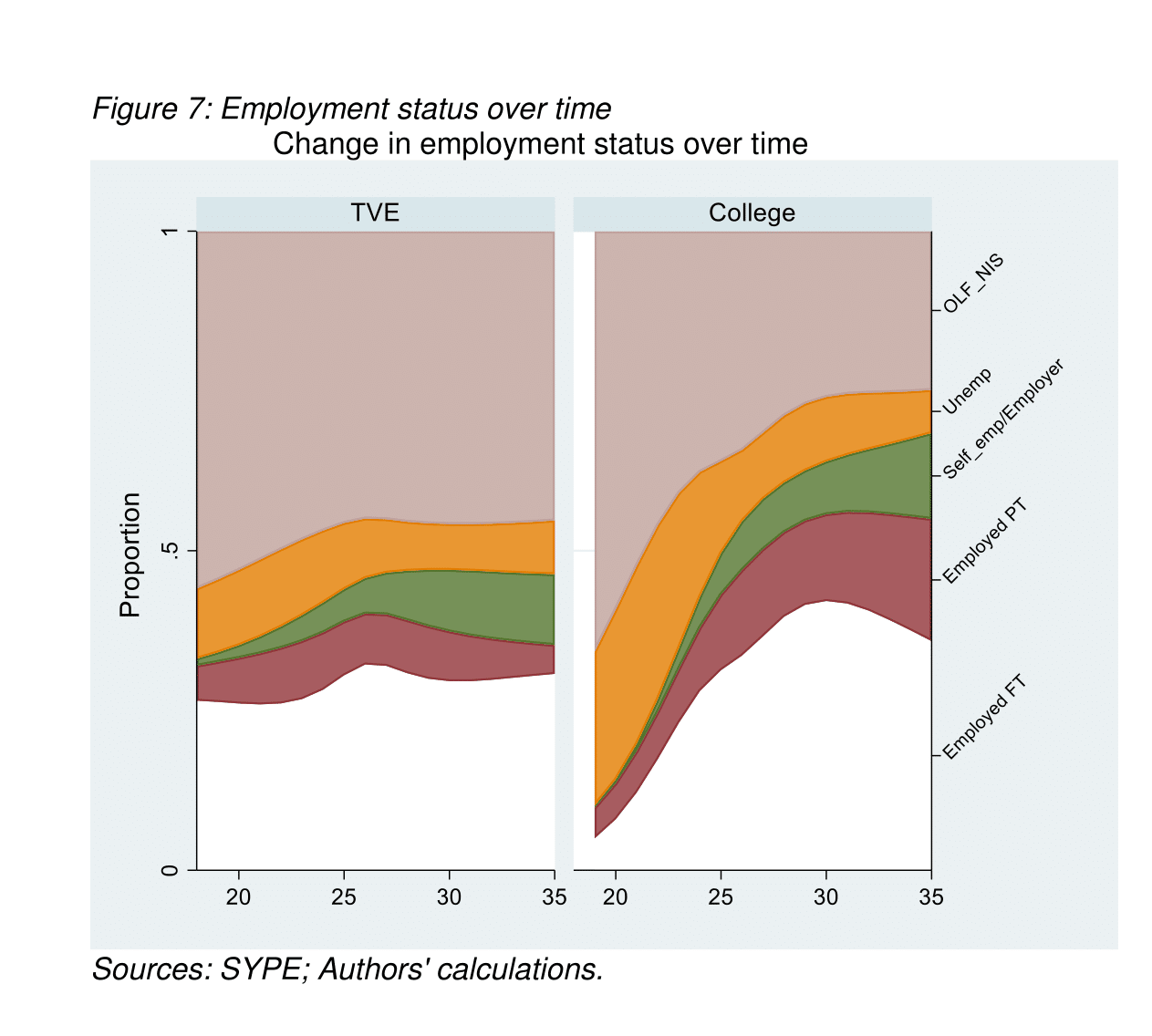

b. Figure 7 reveals that the probability of having a full-time job increases with age and then declines for both groups of graduates, but this transition is more pronounced for college graduates. The likelihood of engaging in full-time employment rises up to age 27 for TVE graduates, and up to age 30 for college graduates.

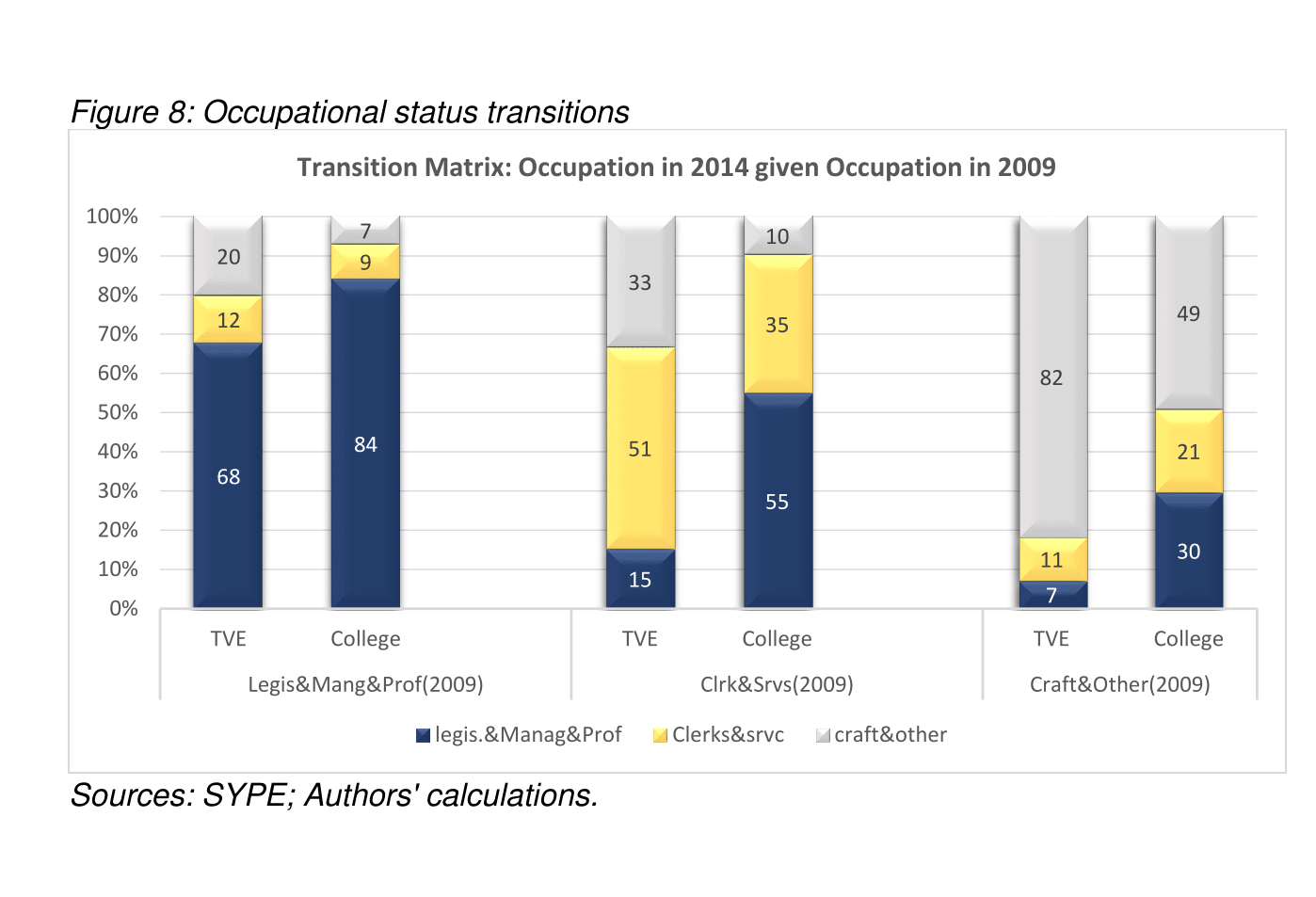

c. Figure 8 shows vertical movements along the hierarchy of occupations, broadly classified as:

- Category 1, the highly skilled group, which includes legislators, managers and professionals, and Technical & Associates (full-time, stable and respected occupations that require at least a college education).

- Category 2, the semi-skilled group, which includes clerks and service workers, and requires at least a high middle school degree.

- Category 3, which includes crafts, machine operators and elementary occupations, which do not require any skill or education and represents unskilled groups.

Figure 8 shows that over 50% of college graduates who start with a job for which they are overqualified are more likely to upgrade to a higher skill occupation compared with TVE graduates. Similarly, a little over 50% of college graduates working in unskilled occupations in 2009 moved up to skilled and semi-skilled occupations in 2014. Yet, only 18% of TVE graduates upgraded from unskilled occupations in 2009 to semi-skilled occupations in 2014, and 32% lost prestigious jobs they once held in 2009.

Figure 8 also shows a small minority of TVE graduates successfully upgraded to skilled occupations for which they have no matching qualifications. There are two possible explanations:

- First, additional years of labour market experiences, compared with recent college graduates, may play a factor.

- Second, the lucky minority of TVE graduates are probably the highest achievers of their class, who are replacing poorly performing college graduates.

Recommended policies

The current initiative of partnership between the government and the private sector is a step in the right direction. But media coverage has ignored the issue of the quality of TVE. Implementing a system of accreditation that is tied to quality assurance for TVE providers is a practice used in developed countries. Teachers, curriculum developers and the media should all be involved as well.

It is also essential to map the demand for and supply of skills in different economic sectors, including cognitive, technical and non-technical (social and behavioural) skills. Tools such as the World Bank Skills toward Employment and Productivity (STEP) survey, which is underway in some countries in the region, would be of great value for policy-makers.

Together with a comprehensive database, this should ultimately provide:

- A searchable data platform to compare employability and salaries across types of degrees and institutions, as well as providing information about the quality and cost of programmes.

- Information about the labour market and the right incentives for students and employers – for example, policies to ensure that technical jobs are filled with graduates of technical schools.

- A platform to facilitate direct connection between graduates and employers.

- Varying dissemination outlets – internet, community town halls, schools, job fairs, etc. – to maximise outreach efforts.

Further reading

Amer, Mona (2007) ‘Transition from Education to Work’, Egypt Country Report, ETF working document.

Assaad, Ragui, and Caroline Krafft (2014) ‘Youth Transitions in Egypt: School, Work, and Family Formation in an Era of Changing Opportunities’, Working Paper 14-1, Silatech.

Barsoum, G, R Mohamed and M Mona M (2014) ‘Labor Market Transitions of Young Women and Men in Egypt’, ILO.

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), Cairo (2016) Statistical yearbook.

Jemmali, H, and F El-Hamidi (2018) ‘Does it Still Pay to Go to College?’, forthcoming.

Roushdy, Rania, and Maia Sieverding (2015) Summary Report: Panel Survey of Young People in Egypt 2014 – Generating Evidence for Policy, Programs, and Research, Cairo: Population Council.

Said, M (2015) ‘Policies and Interventions on Youth Employment in Egypt’.