In a nutshell

Demographic transformations create a window of opportunity to achieve faster economic growth in middle-income economies, but the window lasts approximately for one generation only.

Without major investments in skills across North Africa, the demographic transformation may fail to live up to its promise in a world of rapid technological change.

To meet the demand for high-skilled jobs in the domestic economy policy-makers must equip workers with the right skills; this applies to both young graduates and mid-career workers that may need support with retraining.

Many emerging markets are currently undergoing fast demographic transitions that will have profound effects on how their economies function in the near future.

Only ten years ago, countries where labour force growth outpaced population growth accounted for 90% of emerging market economies’ contributions to GDP. In sharp contrast, by 2040, labour force growth is expected to exceed population growth in only 20% of emerging markets (see EBRD, 2018). This means that a given rate of productivity growth will translate into lower per capita income growth.

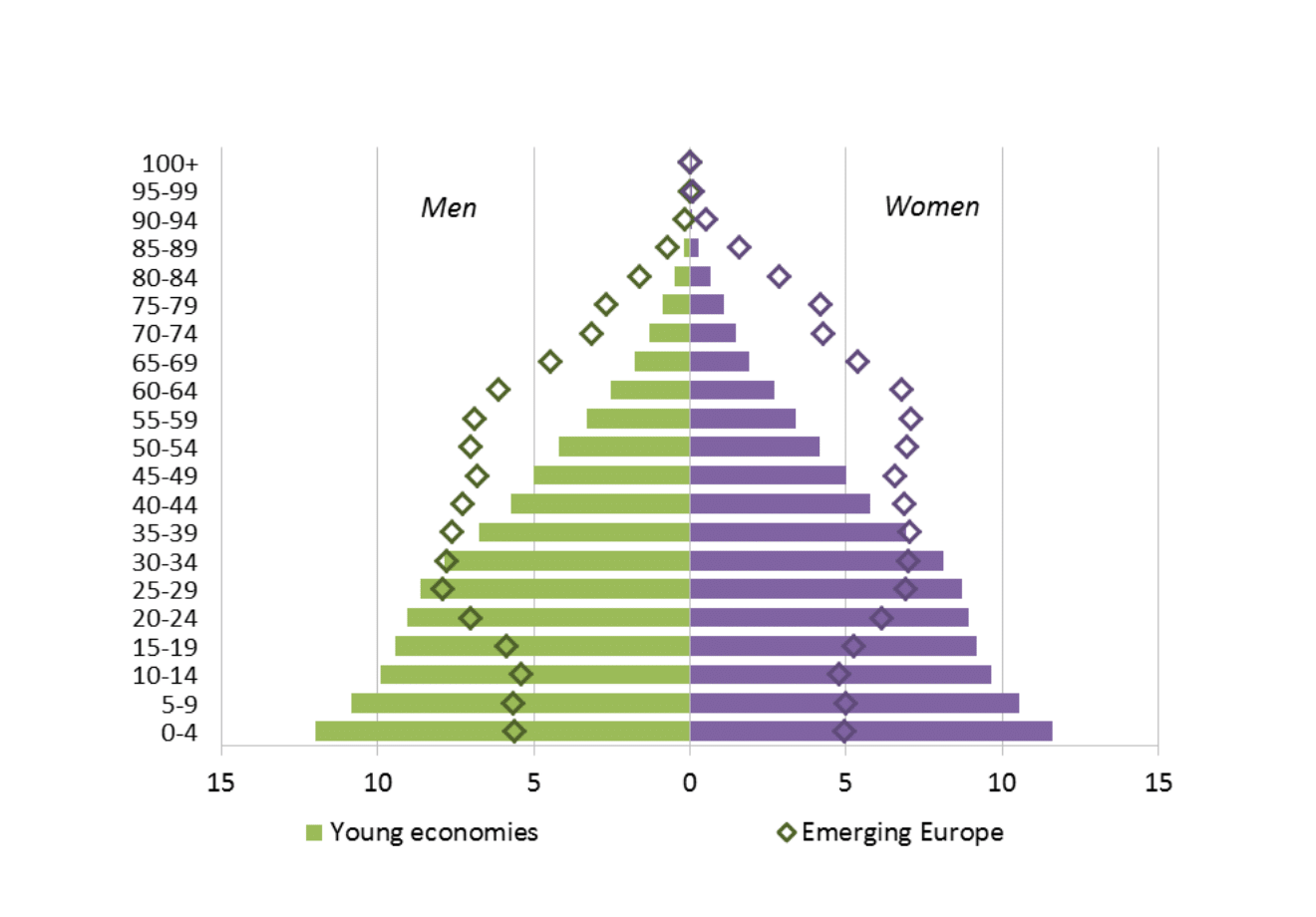

By the standards of middle-income economies, Turkey, North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean are very young. This can be seen in Figure 1, which contrasts the population profiles of these countries with that of ‘emerging Europe’, the fastest-ageing region among emerging markets.

The North African ‘youth bulge’ gives the region a window of opportunity: a chance to achieve faster per capita income growth on the back of its coming demographic transformation. In the past, economies in South East Asia and East Asia have strongly benefited from such demographic tailwinds. Can Turkey, North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean benefit in the same way?

Figure 1:

The youth bulge: the economies of Turkey, North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean (‘Young economies’) have much younger populations than emerging Europe

Source: United Nations and authors’ calculations.

Note: Based on data for 2017 or the latest year available. Young economies aggregate consists of Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia and Turkey.

The key to taking advantage of the region’s demographic profile is substantial investment in skills and education. Because of the rapidly evolving nature of technology, which increasingly polarises jobs into low-skilled and high-skilled occupations, the need to focus public policy on education and ‘upskilling’ is much greater and more urgent than in the past.

Indeed, the demographic window of opportunity may be shorter than policy-makers assume. For example, Turkey’s old-age dependency ratio is projected to rise from around 12% today to 25% in 2040.

From demographic dividend to demographic burden

As low-income countries develop, they can reap so-called ‘demographic dividends’ (Bloom et al, 2003). As incomes rise, life expectancy improves and the birth rate tends to fall. In the early stages of economic development, this results in the working-age population growing much faster than the number of young and old people.

In addition, labour force participation among women tends to increase as the birth rate declines (although trends vary in accordance with prevailing social norms). Strong labour force growth, in turn, raises the growth rate of per capita income for any given rate of output per worker.

As improvements in the standard of living and healthcare gradually translate into rising life expectancy, individuals, firms and governments also start to save more in anticipation of the need to finance future retirement. This increased savings rate enables an economy to sustain higher investment rates, thus boosting the stock of physical capital per worker and, in turn, labour productivity.

Empirically, an even stronger effect arises due to investment in human capital. Greater life expectancy raises lifelong returns to education, while lower fertility rates enable both parents and the state to commit more resources to educating each student. In the words of Becker and Lewis (1973), a decline in the number of children translates into an increase in their quality.

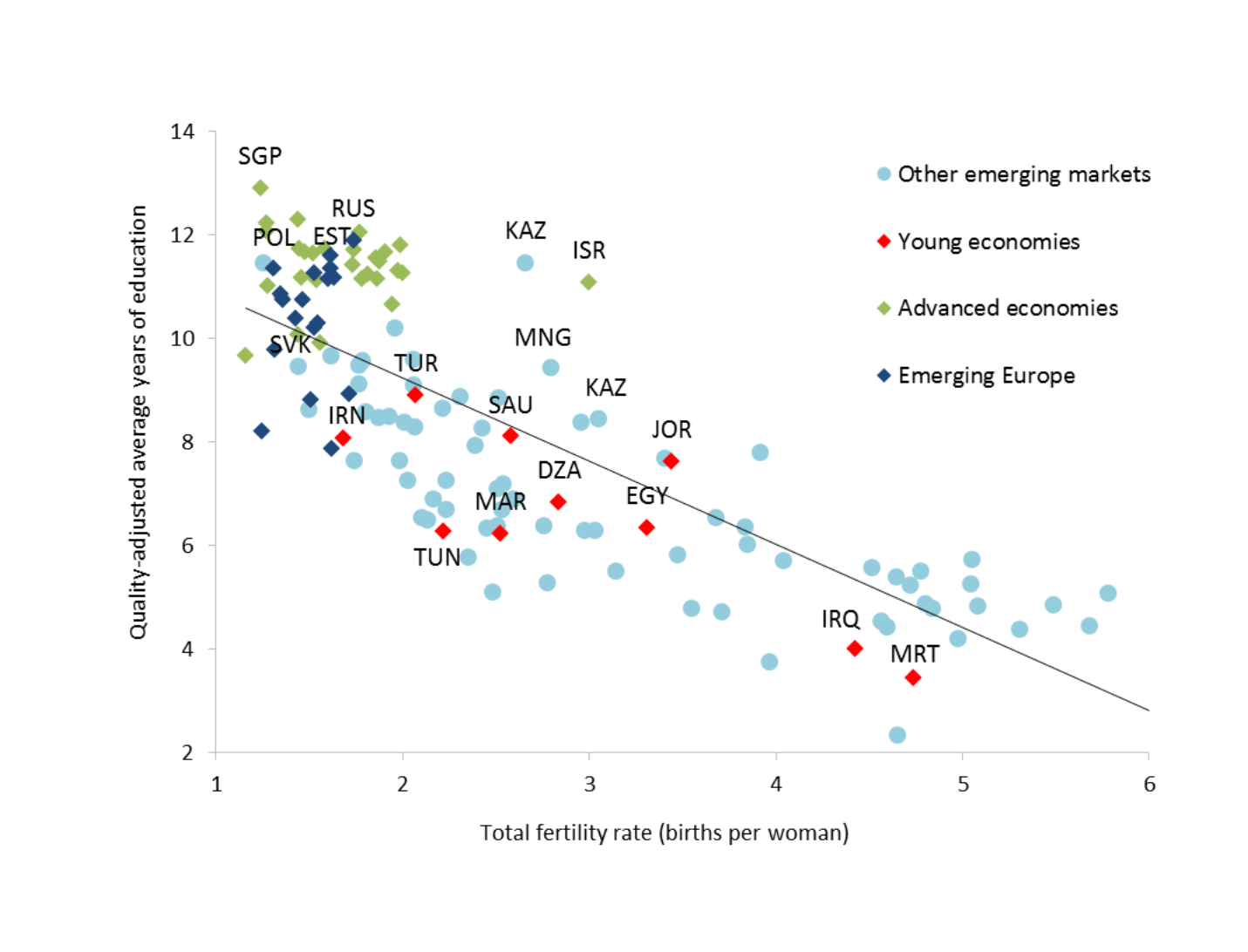

Figure 2 shows a strong relationship between higher average years of education and lower birth rates. This faster accumulation of human capital further boosts productivity growth.

Figure 2:

Average years of education increase as the total fertility rate declines

Source: World Bank, United Nations and authors’ calculations.

Yet this demographic dividend can quickly turn into a demographic burden. As life expectancy rises and the birth rate falls, a country’s population starts to age. As fewer workers enter the labour force and more workers retire, the ratio of the labour force to the total population starts to decline again. Accumulated pension obligations require higher taxes.

In addition, as the age of the median worker rises, it becomes ever harder to retain and update the skills of the labour force. In sum, demographic transformations create a window of opportunity to achieve faster economic growth in middle-income economies, but the window lasts approximately for one generation only (World Bank, 2015).

Leveraging the demographic transformation while it lasts

As young economies are yet to reap the second demographic dividend, they tend to have lower levels of both human and physical capital per working-age adult. The challenge of boosting physical and human capital in these economies today is somewhat different from a similar challenge faced by developing economies in the past, for example, in South East Asia and Latin America.

Previously, automation that accompanies the accumulation of physical capital mainly created medium-skilled jobs, whether in factories or in accounting and finance. It strengthened demand for the gradual upskilling of the workforce and, in turn, supported such upskilling.

Today, however, automation primarily affects medium-skilled routine tasks. It tends to hollow out the medium-skilled segment of the labour market, while creating demand for low-skilled jobs that cannot be easily automated (such as cleaning) and high-skilled ones (such as software engineering) – see IDB et al (2018).

Making sure that the demand for high-skilled jobs can be met in the domestic economy puts a greater onus on policy-makers to equip workers with the right skills. This applies to both young graduates and mid-career workers that may need support with retraining.

In Turkey, North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean, addressing skills deficits may be a particular challenge. This challenge is often hard to quantify as surveys of skills in these economies are few and far between.

The latest human capital index published by the World Bank suggests that years of schooling are relatively low when adjusted for the quality of education. Turkey, the only economy in the region that participated in the Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies, conducted by the OECD in 2011-14, scores well below many advanced and emerging economies in terms of numeracy, literacy and problem-solving tests across all age groups.

Without major investments in skills across North Africa, the demographic transformation may fail to live up to its promise in a world of rapid technological change. This year’s EBRD Transition Report on ‘Work in Transition’ provides more data, analysis and policy recommendations on how countries can ensure they use the coming demographic transition to their best advantage.

Further reading

Becker, G, and HG Lewis (1973) ‘On the Interaction between the Quantity and Quality of Children’, Journal of Political Economy 81: S279-88.

Bloom, D, D Canning and J Sevilla (2003) ‘The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change’, RAND Monograph MR 1274.

EBRD, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2018) Transition Report 2018-19: Work in Transition, London.

IDB (Inter-American Development Bank), AfDB (African Development Bank), ADB (Asian Development Bank) and EBRD (2018) The Future of Work: Regional Perspectives, Washington, DC.

World Bank (2015) Global Monitoring Report 2015-16: Development Goals in an Era of Demographic Change, Washington, DC.