In a nutshell

When not invested efficiently, aid inflows can cause a drastic change in the structure of the economy, undermining long-term growth.

Aid volatility could be detrimental to economic growth, especially in oil-poor countries with restricted fiscal space, such as Syria and Yemen.

In countries with relatively low quality economic and political institutions, aid could be wasted on ‘white elephant’ projects and clientelism, as happened in Lebanon.

The ability of national authorities in conflict-affected countries such as Syria and Yemen to provide required humanitarian aid and to continue investing in long-term development will be limited, especially if they rely solely on domestic resource mobilisation. Such duality in spending right after civil conflict is essential, but often beyond a fragile state’s fiscal capacity.

For this reason, there is usually a need for additional resources from the international community in the form of concessional loans, donations and bilateral transfers. Collier and Hoeffler (2002) and ESCWA (2019) find that such international aid boosts the growth of recipient economies, at least in the first decade after a conflict. But governments should be aware of the associated macroeconomic issues arising from such inflows and their impact, especially on tradable goods sectors (Aiyar et al, 2005).

There are three key lessons to be learned from countries that have previously experienced civil conflict in order to avoid aid-related economic pitfalls and to enhance the effectiveness of foreign assistance in post-conflict reconstruction.

Aid and the structure of the economy

First, when not invested efficiently, aid inflows can cause a drastic change in the structure of the economy, undermining long-term growth and putting productive sectors at the periphery in favour of non-productive ones through the ‘Dutch disease’ effect. This is a particular problem when aid as a percentage of GDP is significantly high, supply-side bottlenecks are present and aid is provided for a limited time period.

The conventional recipe for post-conflict reconstruction is investing in non-tradable sectors, namely infrastructure, health and education, for which there are pressing humanitarian and consumptions needs.

Yet an excessive disproportionate allocation of aid towards these sectors may harm the competitiveness of exports, especially in the short run through the resource movement and spending mechanisms (Corden and Neary, 1982; Rajan and Subramanian, 2011). That is to say, such spending may drive wages up in non-tradable sectors and prompt factor reallocation, specifically skilled labour, away from the tradable sectors.

In addition, the increase in the relative demand for the non-tradable goods and the spending of higher wages may also induce a real exchange rate appreciation that further impairs the profitability, competitiveness and growth of tradable sectors (Rajan and Subramanian, 2011).

El-Badawi et al (2008) and ESCWA (2019) also find that aid inflows adversely affect the real exchange rate in post-conflict economies. El-Badawi et al (2008) argue that although the resulting overvaluation of the real exchange rate is fairly moderate, it may still hamper economic growth.

The existence of sound and developed financial markets may smooth out the effect of aid on relative prices and offset the Dutch disease risk (Donmez, 2005). Nonetheless, this is highly improbable in conflict-affected countries such as Syria, in which a poorly established financial sector, even prior to the war, exacerbates the adverse effects of aid on growth (El-Badawi et al, 2008; ESCWA, 2019).

Moreover, the combination of increased aid inflows and the share of oil exports in GDP, as in the case of Syria, may amplify the exchange rate misalignment (ESCWA, 2019). Generally, foreign aid’s role in fostering growth is curbed in a macroeconomic environment of exchange rate overvaluation (El-Badawi and Soto, 2013).

Aid volatility and growth

Second, aid volatility could be detrimental to economic growth, especially in oil-poor countries with restricted fiscal space such as Syria and Yemen. The fiscal revenues in Syria and Yemen are primarily dependent on taxation, particularly taxes on corporate and personal incomes.

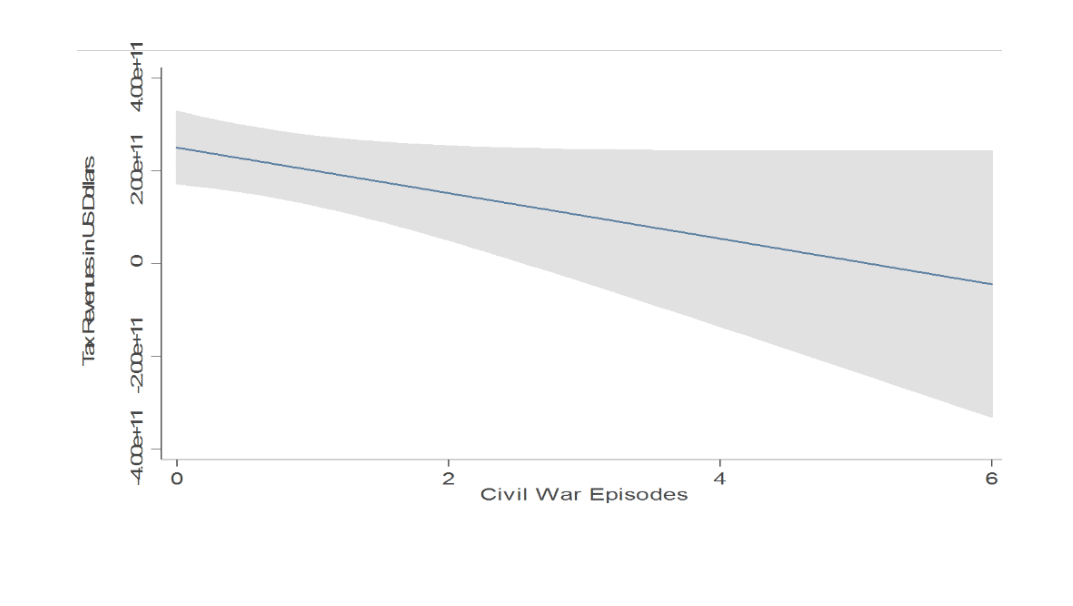

Araji (2017) examines 11 countries that have experienced civil war in the past two decades, and finds a significantly negative impact on tax revenues (see Figure 1). Hence, in the aftermath of the crisis, it is challenging for countries such as Syria and Yemen to mobilise domestic revenues to cope with the reconstruction plan given the shrinking tax base and increasing tax non-compliance, as well as volatility in oil prices. Consequently, fiscal and development planning after the crisis is largely aid-dependent.

As noted in ESCWA (2017), external aid often rises immediately when conflicts end (up to 100% of GDP) and is then followed by domestic subsidies, a pattern clearly that is unsustainable for the entire reconstruction period. A well-established stylised fact is therefore high aid volatility in the post-war period, which affects development planning and spending (Gelb and Eifert, 2005) as well as hampering macroeconomic stability in aid-dependent countries (Bulir and Hamann, 2007).

Aid and institutional quality

Third, in the presence of relatively low institutional quality, aid could be wasted on ‘white elephant’ projects and clientelism (as happened in Lebanon). In this case, aid inflows would be viewed by policy-makers as a substitute for tax revenues. The efficacy of aid is in essence contingent on the institutional framework in the post-conflict period (La Porta et al, 1997; Acemoglu et al, 2001).

ESCWA (2017) particularly emphasises the need for credible and sound public financial management, which maintains transparency about the budget and financial assistance. In a similar institutional context, Boone (1994, 1996) and Burnside and Dollar (2000) accentuate the need for sound macroeconomic policies and management of aid flows. Fiscal, exchange rate and monetary regimes need to be synchronised to reap the economic benefits of aid while minimising potential pressures on inflation and competiveness (ESCWA, 2017).

It is worth noting that post-conflict scenarios all have their own idiosyncrasies, and the key to assessing aid effects and effectiveness is to conduct case-specific analysis and examination of internal conditions, capacity-building needs and priorities.

A lack of coordination with the local community and experts on the reconstruction plan can result in large financial inefficacies and non-fulfilment of projects, as happened with the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq. Donors should therefore tailor their grants to develop economic activity in which the local community is already engaged. This could help to avoid ill-advised policies in post-conflict countries.

In light of these issues, we propose the following options for Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen:

For Syria and Yemen, a stable flow of international aid is required regardless of its size

The optimal option for conflict-affected countries is either to secure a steady flow of aid for the period of post-conflict reconstruction or to look for a secure a flow of domestic revenue mobilisation through taxation, natural resources (to a lesser extent) and/or domestic borrowing while paying due attention to medium and long-term debt sustainability.

In all four countries, international inflows should be targeted toward human capital development (health and education)

In this case, the supply of productive skills and, at the same time, the increase in the supply of non-tradable goods offsets the short-term implications of international aid.

In oil-abundant Iraq and Libya, reconstruction efforts should develop fiscal measures to maintain macroeconomic stability and social stability, as well as promoting structural transformation

Uncertainty in oil revenues is a major challenge. In Iraq, prolonged conflict and low oil prices since 2014 have resulted in a significant loss of revenues, negatively affecting the allocation of resources for development expenditure. Between 2013 and 2015, a larger share of revenues was channelled to military operations and security, and public administration at the cost of social services, education and other development sectors.

While aid is important to maintain economic and social stability, the oil-rich countries should also use oil receipts in sustainable reconstruction in the short term. In the longer term, they need to work out an effective strategy for revenue diversification to reduce their reliance on oil revenues, as a more sustainable economic model.

A focus on reconstructing infrastructure, reactivating pre-war productive sectors and furthering diversification should be a priority in Syria and Yemen

International inflows along with government revenues could be used on reactivating the growth engines of the economy and boost productivity. Governments in such countries can prioritise among sectors based on sector productivity and the potential for employment creation, poverty reduction and gender equality among others.

As for oil-rich countries, this might require the implementation of appropriate fiscal rules (spending and price rules). Prioritisation should consider the short-run environment through urgent consumption and humanitarian needs and the long run through investments in infrastructure, human capital and sector diversification.

In all four countries, major improvement is required in the quality of governance and public financial management

Reactivating fiscal institutions and reforming the institutional and legal settings of the existing fiscal administration can enhance government effectiveness for conflict-affected countries. The post-construction efforts require major legislative and institutional reforms to diversify revenue sources, including through reforms of tax systems and administration, and to improve transparency in government spending.

For the oil-rich countries, such reforms could include the institutional setting of oil and gas revenue management, checks and balances in licensing, national budgeting and transparent management of their sovereign wealth funds.

Further reading

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson and J Robinson (2001) ‘The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation’, American Economic Review 91(5): 1369-1401.

Aiyar, S, A Berg and M Hussain (2005) ‘The Macroeconomic Challenge of More Aid’, Finance and Development 42(3): 28-31.

Araji, S (2017) ‘Fiscal Policy Considerations for Post-war Reconstruction in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Libya, ESCWA Technical Paper No, 14.

Boone, P (1994) ‘The Impact of Foreign Aid on Savings and Growth’, London School of Economics and Political Science: Centre for Economic Performance.

Boone, P (1996) ‘Politics and the Effectiveness of Foreign Aid’, European Economic Review 40(2): 289-329.

Bulíř, A, and AJ Hamann (2007) ‘Volatility of Development Aid: An Update’, IMF Staff Papers 54(4): 727-39.

Burnside, C, and D Dollar (2000) ‘Aid, Policies, and Growth’, American Economic Review 90(4): 847-68.

Collier, P, and A Hoeffler (2002) ‘Aid, Policy and Peace: Reducing the Risks of Civil Conflict’, Defence and Peace Economics 13(6): 435-50.

Corden, M, and P Neary (1982) ‘Booming Sector and De-industrialization in a Small Open Economy’, Economic Journal 92(368): 825-48.

Donmez, A (2005) ‘The Effects of Aid on Inflation: The Role of Financial Market Development’.

El-Badawi, I, L Kaltani and K Schmidt-Hebbel (2008) ‘Foreign Aid, the Real Exchange Rate, and Economic Growth in the Aftermath of Civil Wars’, World Bank Economic Review 22(1): 113-40.

El-Badawi, I, and R Soto (2013) ‘Aid, Exchange Rate Regimes and Post-conflict Monetary Stabilization’, ERF Working Paper No. 751.

ESCWA, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2019) ‘Syria at War: Seven Years On’.

ESCWA (2017) ‘Rethinking Fiscal Policy for the Arab Region’.

Gelb, A, and B Eifert (2005) ‘Improving the Dynamic of Aid: Towards More Predictable Budget Support’, World Bank Policy Research working Paper No. 3732.

La Porta, R, F Lopez-de-Silanes, A Shleifer and RW Vishny (1997) ‘Legal Determinants of External Finance’, Journal of Finance 52(3): 1131-50.

Rajan, R, and A Subramanian (2011) ‘Aid, Dutch Disease, and Manufacturing Growth’, Journal of Development Economics 94(1): 106-108.

Figure 1:

Tax revenues and civil war episodes

Source: Araji, 2017