In a nutshell

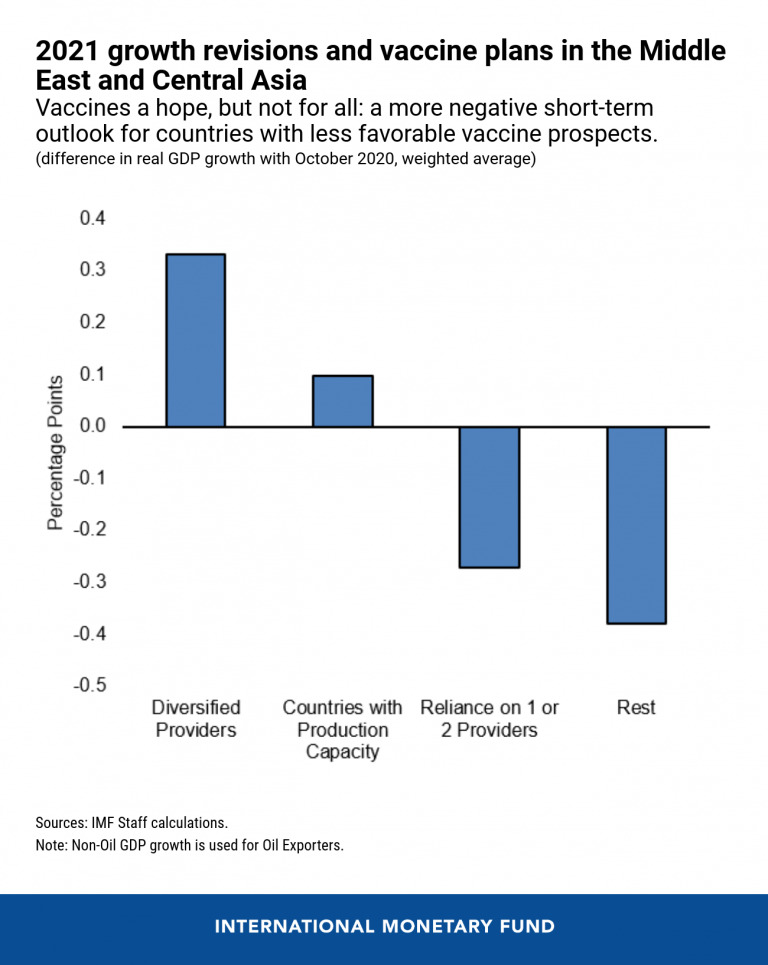

Access to the Covid-19 vaccine will play a critical role in the region’s recovery: countries with diversified vaccine providers and production have more favourable forecasts; the outlook for those with more limited access to vaccines looks weaker.

International and regional cooperation are essential in a world facing an uneven recovery and with vaccine haves and have-nots. Enhancing transparency around vaccine contracts would safeguard access on equal terms.

While much work remains to tackle the immediate crisis, the region must also move swiftly and in parallel on building a resilient, stable, and more inclusive post-pandemic recovery.

The road to recovery for the Middle East and Central Asia region will hinge on containment measures, access to and distribution of vaccines, the scope of policies to support growth, and measures to mitigate economic scarring from the pandemic.

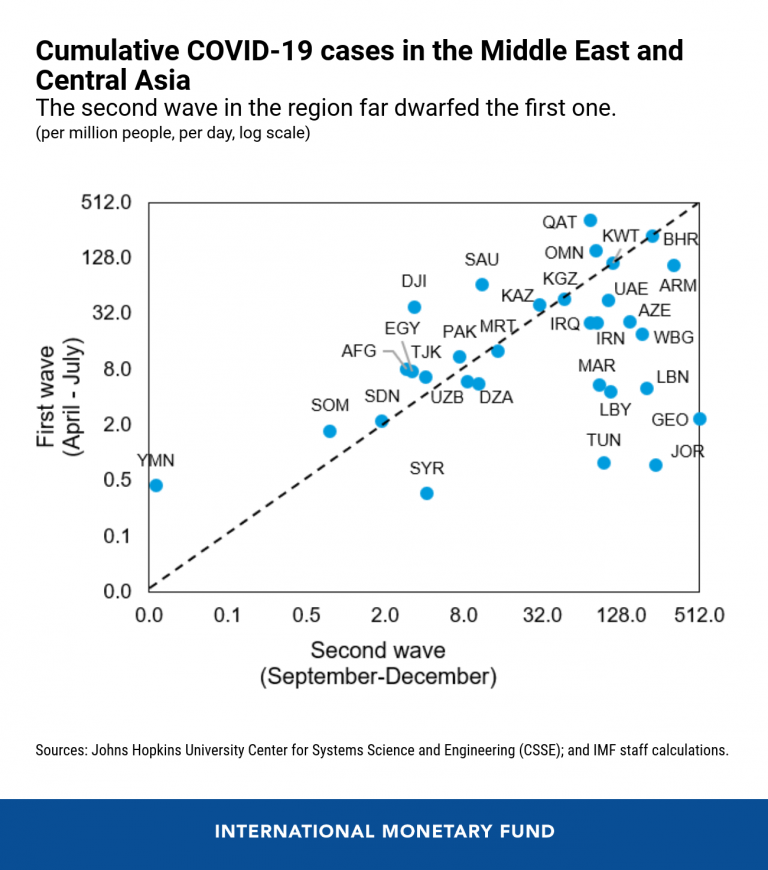

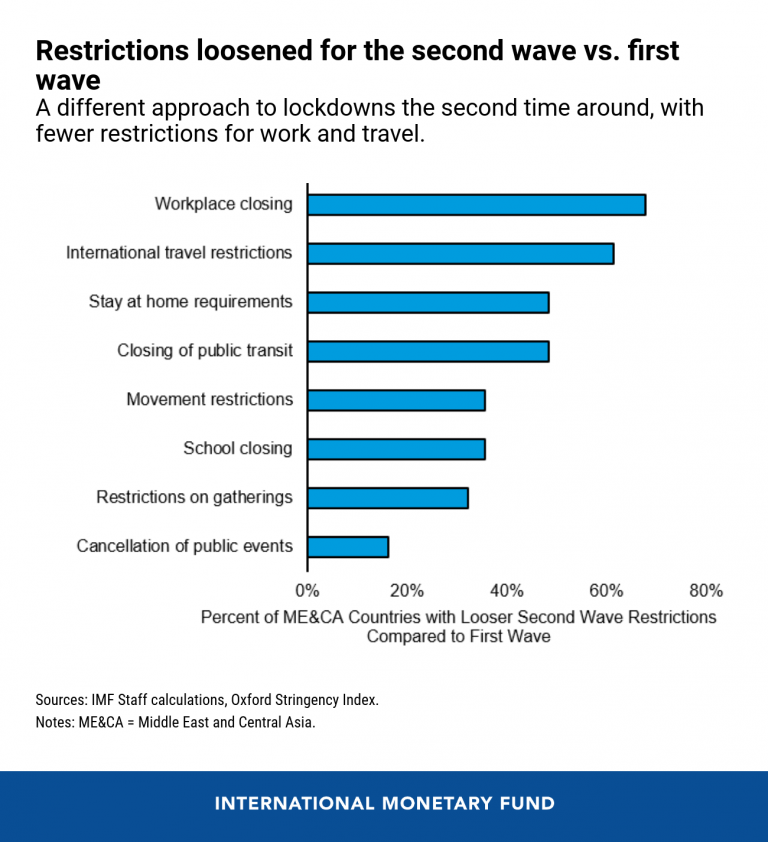

The virus’s second wave, which began in September, hurt many countries in the region, where infection and death rates far surpassed those seen during the first wave. Most countries resumed selective restrictions to help lessen their negative humanitarian and economic impact, while some have started vaccination campaigns.

Uneven access to vaccines

Meanwhile, region-wide disparities on vaccine plans require active policies to avoid prolonging the crisis or uneven recovery:

- Countries in the region with the most diversified vaccine providers (with bilateral agreements covering Chinese, Russian, and western developers) include those in the Gulf Cooperation Council and larger countries with production capacity (Egypt, Morocco, Pakistan). The former have the widest coverage, earliest inoculations, and the most advanced plans, targeting agreements that in some cases include doses in excess of those needed to inoculate the entire population.

- A few other countries, including several in the Caucasus and Central Asia region, also expect to achieve high coverage but are relying on one or two providers, which may delay the speed of inoculations.

- Many countries, however, including fragile and conflict-affected states, remain reliant on the limited coverage of the World Health Organization’s COVAX initiative. Risks facing them are especially high, given their limited healthcare capacity and the underfunding of COVAX, which could delay broad vaccine availability until the second half of 2022.

Divergent recoveries

Since our October Regional Economic Outlook, growth estimates for 2020 have been revised up for the Middle East and North Africa region by 1.2 percentage points, to an overall contraction of 3.8%. This is largely driven by stronger-than-expected performance among oil exporters, as the absence of the second wave in some countries boosted non-oil activity, and the impact of the first wave was lower than expected.

For the Caucasus and Central Asia region, 2020 growth, on average, remains unchanged (a contraction of 2.1%), as some countries’ stronger growth early in the year is estimated to have been offset by weaker fourth quarter activity due to the second wave, while others saw a worse-than-expected impact of shocks throughout the year.

Access to the Covid-19 vaccine will play a critical role in the recovery ahead. For 2021, our projections relative to October are broadly unchanged but reflect significant differences among countries: those with diversified vaccine providers and production have more favourable or broadly unchanged forecasts, while the outlook for those with more limited access to vaccines and those harder hit by the second wave looks weaker.

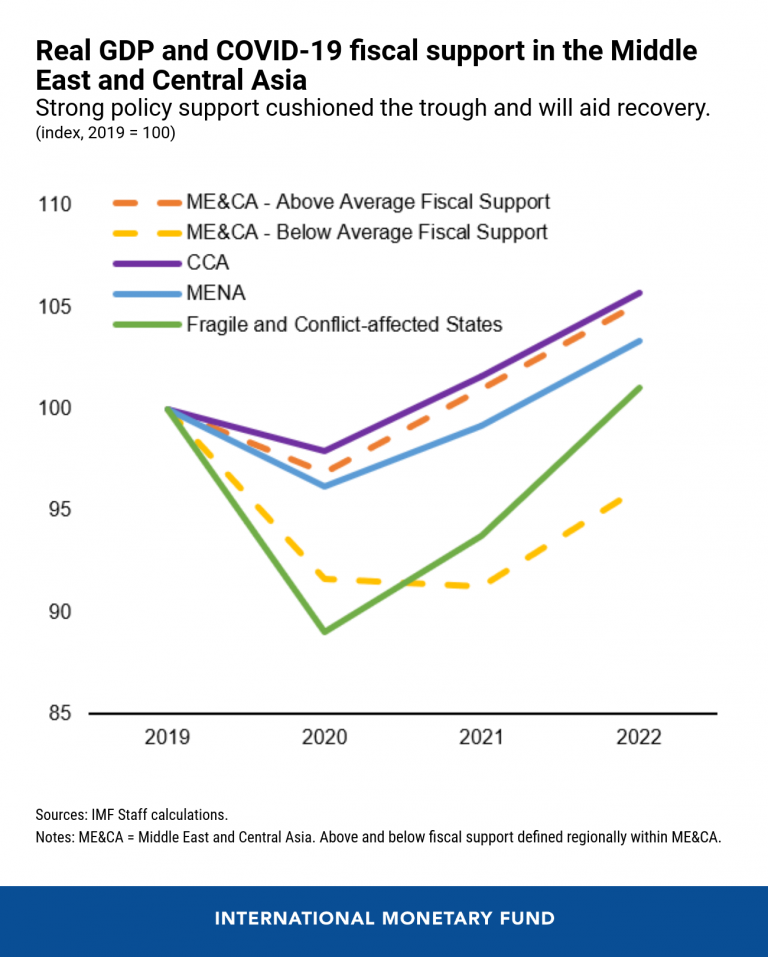

Additionally, countries that put in place stronger fiscal and monetary support in response to Covid-19 are also expected to have a stronger recovery, aided by a shallower trough in 2020. In particular, while Caucasus and Central Asia countries as a group are projected to reach 2019 GDP levels in 2021 – due to their stronger Covid-19 response – those heavily impacted by the second wave will lag behind and not regain pre-pandemic GDP levels until 2022.

Nonetheless, recovery in the Middle East and Central Asia region’s emerging markets is projected to lag that of their peers elsewhere, with most countries not recouping 2019 GDP levels until 2022. Fragile and conflict-affected states will be especially battered, with 2021 GDP levels projected at 6% lower than in 2019.

Sizable uncertainty remains

Risks remain high. Renewed infections could delay recovery in the absence of vaccines and policy space. Recent mutations of the virus could pose additional challenges. Further spending needs could exacerbate debt sustainability concerns in several countries, especially if a sharp rise in global risk premia or higher-than-expected increase in global interest rates tighten financing conditions and raise roll-over risks. Lastly, delays in or mismanagement of vaccine distribution, together with higher vulnerabilities, could rekindle social unrest.

Limited policy space

While vaccines shine a light of hope, the path will be long and winding. In the short term, the main priority remains ensuring that healthcare systems are adequately resourced, including funding vaccine purchases and distribution as well as continuing investment in testing, therapies, and personal protective equipment. People’s health will be critical to anchor the recovery.

Balancing between supporting the recovery and preserving debt sustainability will be challenging for the region, given that fiscal space is limited (fiscal balances worsened by more than 5 percentage points of GDP in 2020 for one-third of the countries) and consolidation will need to resume in 2021 for numerous countries.

If renewed infections endanger the recovery, countries that have some fiscal space (such as Kazakhstan and Qatar) could reinforce temporary support – until wide vaccine availability – through lifelines to vulnerable households and viable firms.

Countries with narrow or no fiscal space, whose debt to GDP reached an average of 72% in 2020 (an increase of 11 percentage points), should maintain or reallocate spending towards targeted policies with the largest social and economic impact, such as priority health spending, investing in youth, and upskilling the labour force. Given narrow fiscal space, to support demand, monetary policy should remain accommodative where inflation and external sustainability are not at risk. In countries with flexible currencies, the exchange rate should continue to act as a buffer when needed.

Cooperation critical to reducing divergence

International and regional cooperation are essential in a world facing an uneven recovery and with vaccine haves and have-nots. Enhancing transparency around vaccine contracts would safeguard access on equal terms.

Supporting poorer countries and countries in fragility or conflict to ensure equitable access is critical, as is the need to bolster funding for COVAX. Regional coordination would facilitate redistribution of excess vaccines from those that have secured surplus (including from domestic production capacity) to those with insufficient supplies. Fragile and conflict-affected states should receive priority to prevent further humanitarian tragedies.

The IMF, which provided sizable financing to the region last year ($17.3 billion), stands ready to continue helping countries tackle the crisis and shift towards recovery through financing, technical assistance, and policy advice.

Accelerating recovery

While much work remains to tackle the immediate crisis, the region must also move swiftly and in parallel on building a resilient, stable, and more inclusive post-pandemic recovery. This requires addressing the uneven labour market impact of the crisis and curbing rising inequality, strengthening social protection, tackling crisis legacies, in particular debt overhang, reforming state-owned enterprises and reducing state footprint in the economy, and fighting corruption. To accelerate the recovery and avoid a lost decade, work should start now on high-quality investment in green infrastructure and digitalisation.

This article first appeared on the IMF blog here.