In a nutshell

Women in Egypt perform the vast majority of unpaid care work – and marriage is a key determinant of increased time use. Married women spend seven times as much time on domestic work as married men – and this is true whether or not they are employed.

The double burden of paid and unpaid work is an important barrier to women’s participation in the labour force – and it is something that will continue unless measures are taken to reduce and redistribute women’s unpaid care responsibilities.

Expanding decent jobs in the care economy in the private sector can be a major driver of private sector employment growth and women’s engagement in paid work. Expansion of high-quality early childhood care and education services is essential.

Women in Egypt perform the vast majority of unpaid care work, and this consumes a significant proportion of their time – time that could be allocated to paid work, education, leisure, self-care activities or other pursuits. Women’s participation in unpaid care work is almost universal, with 88% of working-age women involved in such work in 2018 compared with only 29% of men (ERF and UN Women, 2020).

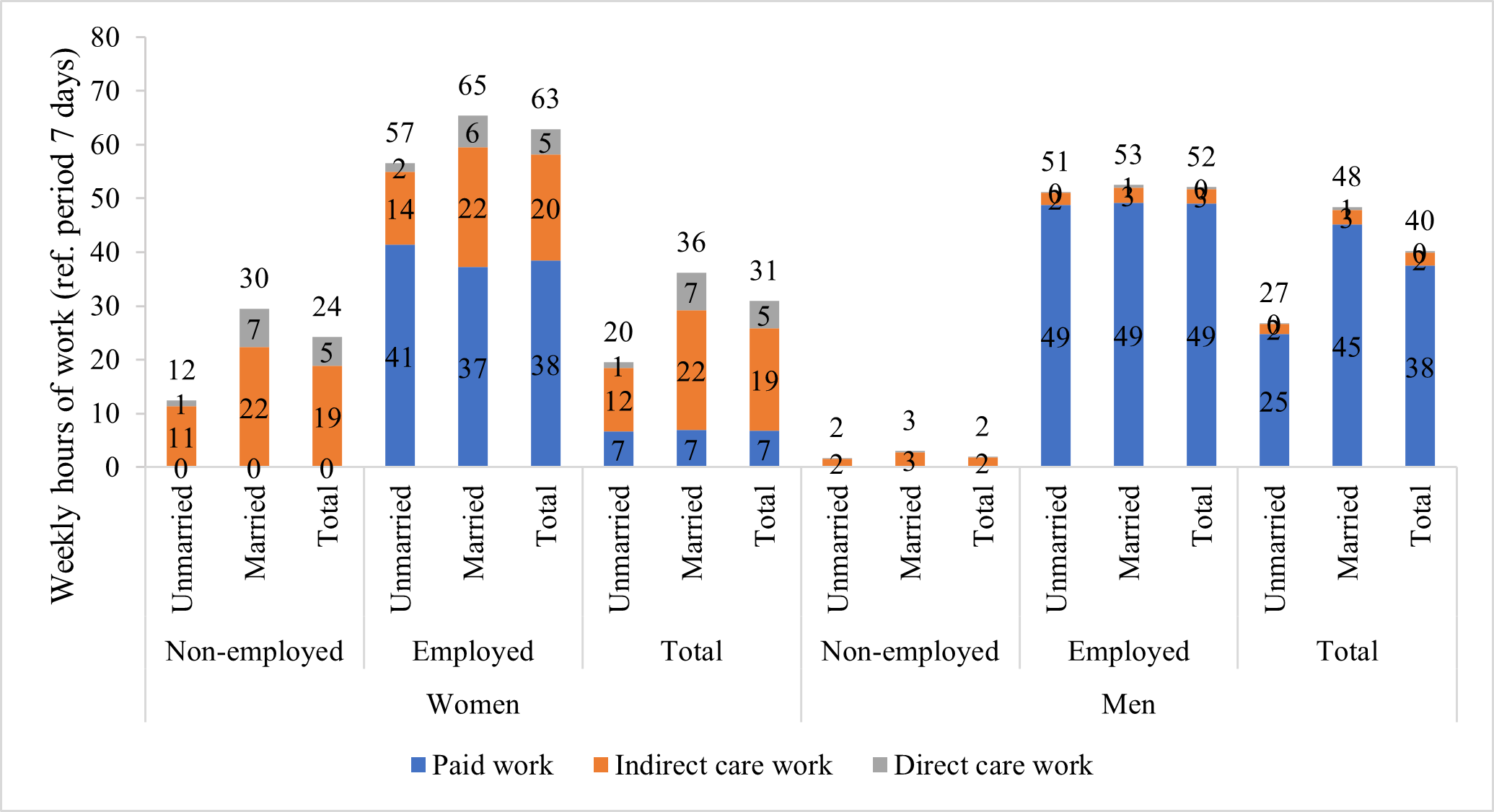

Marriage is the key determinant of how much time women spend on unpaid care activities, with married women spending twice as much time as unmarried women (Figure 1). Married women spend almost the same amount of time on unpaid care work whether or not they are employed. Employed married women perform the highest number of hours per week of total work (paid and unpaid), far exceeding the number of hours of their male peers.

This double burden is an important barrier to women’s participation in the labour force, and it is something that will continue unless measures are taken to reduce and redistribute women’s unpaid care responsibilities. It is thus necessary to implement employment regulations that promote flexible and part-time work arrangements to improve work-life balance, particularly for married women.

Moreover, promoting gender-neutral policies can help to redistribute unpaid care work. Regulations that only apply to women can be costly to employers and tend to discourage employers from recruiting women.

For example, the current labour law stipulates that employers establish a nursery once they hire 100 women workers or more. This policy has probably discouraged many employers from hiring more than 99 women workers, and it may explain why the share of employer-initiated nurseries does not exceed 2% of total nurseries in Egypt.

A reform such as that recently implemented in Jordan, which based the requirements for opening a nursery on the total number of young children of all employees, rather than just women employees, could help to reduce this disincentive.

Care leaves, including paternity or parental leave, constitute an important pillar for any comprehensive approach to care policy. Maternity leaves – which are fully financed by the employer – may also discourage employers from hiring women.

Accordingly, there is room to restructure the financing scheme of maternity leave to move from a system that puts the main liability on employers and reduces incentives for hiring women, to a maternity insurance system. Care leaves and related provisions should be offered to all employees, regardless of gender, to avoid further reinforcing the prevailing norm that care work is ‘women’s work’.

Figure 1: Weekly hours of paid work and unpaid care work (direct and indirect) by sex, employment and marital status, ages 15-64, ELMPS 2012

Source: Authors’ calculation based on ELMPS (Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey) 2012.

Note: Indirect care work consists of tasks that do not involve face-to-face interaction, but that are needed to sustain direct care, including cleaning, cooking, shopping for household items and maintenance work within the home. Direct care work involves personal, relational activities of taking care of another person, such as nursing a baby, reading to a child or helping an elderly person to dress or take a bath.

Family structure and the mismatch between care needs and paid care services in the market

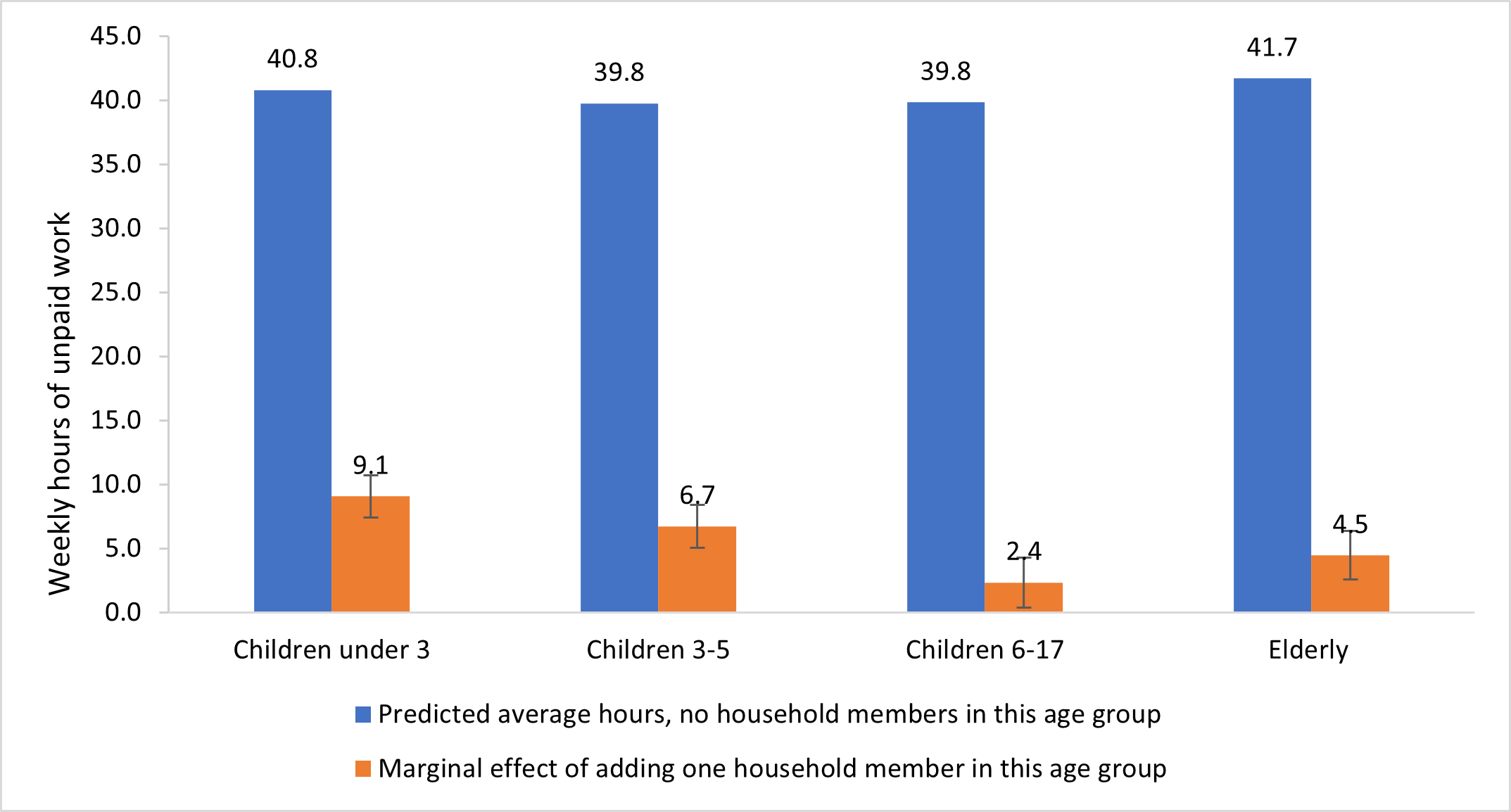

Women’s time spent on unpaid care work also depends on family structure. The largest effect on married women’s time spent on unpaid care work results from having a child aged 0-3 or 3-5 in the household (Figure 2).

At the same time, there is a strong gap in the availability and adequacy of childcare services in the market. For example, in 2017, the number of childcare institutions serving children aged 0-3 in Egypt was limited (20,679 establishments) compared with the number of children aged 0-3 (over 11 million). This contributes to a low enrolment rate (8%) for children in this age group.

Previous research confirms that employed women face difficulties arranging childcare, because high-quality facilities are either not available or not affordable (Constant et al, 2020). It is thus important to expand access to affordable and high-quality childcare options for women, through public policy and private sector engagement. This would serve the dual goals of supporting children’s development and women’s ability to join and remain in the labour force.

Reforms to develop early childhood education must ensure that all children are offered equal opportunities to learn and thrive. This is crucial to reduce gender and social inequalities, since children from wealthier families are six times more likely to enrol in pre-primary education than those from poorer families. This negatively affects both these children’s chances for strong early childhood development and the opportunities of their mothers to engage in paid employment (El-Kogali and Krafft, 2015).

Subsidising quality childcare for the poor is an important area for public interventions to support the outreach of early childhood care and education services to different vulnerable groups. Evidence from Kenya shows that offering subsidised early childcare can positively affect women’s employment and economic participation (Clark et al, 2019). Such interventions could also ensure that reliance on private services, rather than the state, does not exacerbate gender or socioeconomic inequalities.

Public and private provision of elder care in Egypt also requires further development. Information and data about this sector is scarce and often contradictory. Yet it is one of the most important areas of improvement because the elder population will continue to grow considerably in Egypt in coming decades. Without policies to develop adequate elder care services, this expected increase will lead to higher unpaid care responsibilities.

First, it is important to address the falling rates of workers covered by social insurance to ensure a decent level of pension coverage in old age. The New Social Insurance and Pension Act, introduced in 2019, is a first reform to curb the rising proportion of socially uncovered workers.

Second, there is a strong need to expand high-quality residential and non-residential care services for the elderly. This could be achieved by encouraging the private sector to invest in these services through improving the business climate, simplifying tax procedures, and providing access to adequate funding. Another area of action is to encourage and promote professional nursing, so as to increase the availability of quality home-based care services.

Figure 2: Predicted additional weekly hours of care work with one care recipient of different ages in the household, married women age 15-64, ELMPS 2006

Source: Authors’ predictions based on OLS regression using ELMPS 2006.

Note: The grey bars indicate 95% confidence intervals on the estimates of additional time.

The paid care economy: growth at the expense of quality?

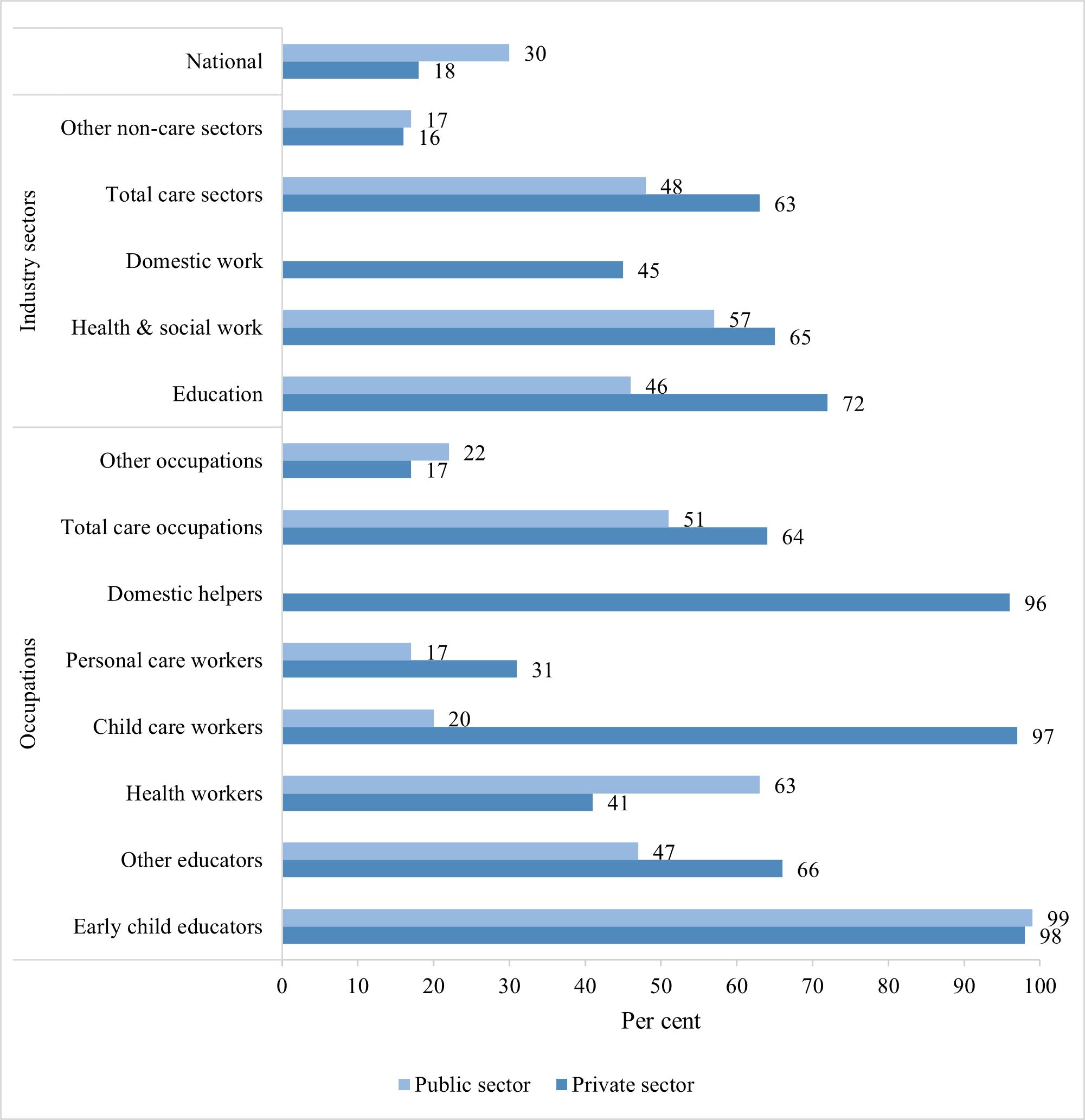

Just as women perform most of the unpaid care work, they are also more likely to perform paid care work. Women were almost four times more likely than men to be employed in paid care sectors (health, education, social work or domestic work) compared with other sectors of the economy (Figure 3).

Most paid care jobs are concentrated in the public sector. Yet, the share of the private sector in paid care employment has grown considerably – from 13% of all care sector jobs in 2009-11 to 25% in 2015-17. Over this period, employment in the private paid care sector grew faster than in other parts of the private sector.

Moreover, over time, the proportion of women employed in the private sector has also grown faster in care sectors compared with non-care sectors. Given women’s weak participation in Egypt’s private sector in general, the care economy can be an important source of expanding job opportunities for women.

Yet while being the largest employer of women and the one with highest formality rates, the care sector has experienced deteriorating job quality – captured by rising informality. Thus, any expansion of the paid care sector must focus on job quality. Efforts to reverse the trend of declining job quality are needed to encourage the expansion of decent care jobs.

There is also a strong association between working conditions in paid care jobs and the quality of service provided. While there is little information on the quality of early childhood care and education services and elderly care services, worsening job quality may indicate heightened quality issues in provision as well.

Figure 3: Proportion of women, by industry sectors and care occupations compared with other sectors/occupations and by institutional sector, LFS 2015-17

Source: Authors’ calculations based on LFS 2015-17.

Why is the re-emergence of the missing middle a welcome development?

Another development is that the proportion of married women in the expanding private paid care sector has fallen. This is either because labour market regulations lead to higher costs to employers when they recruit a married woman than an unmarried one, or because married women abstain more from the labour market as they fail to find formal jobs in the private sector.

Thus, reforms should be centred around how to improve private sector working conditions and job quality – including working hours, care provisions, social security benefits and safety of workplaces – to make such work more hospitable to women, and reconcilable with domestic care responsibilities and social values.

It is crucial to fix the structural problems of the labour market – namely deterioration of the business climate, high taxes/social security contribution rates, and limited access to finance that micro, small and medium-sized enterprises suffer – as these types of enterprises are likely to constitute the majority of nurseries and elder care facilities.

Without proper investment in the paid care economy, gender imbalances in both unpaid care work and paid work will continue, taking their toll on human capital, social justice and economic growth.

Further reading

ERF and UN Women (2020) Progress of Women in the Arab States 2020: The role of the care economy in promoting gender equality.

Clark, S, CW Kabiru, S Laszlo and S Muthuri (2019) ‘The Impact of Childcare on Poor Urban Women’s Economic Empowerment in Africa’, Demography.

Constant, L, I Edochie, P Glick, J Martini and C Garber (2020) Barriers to Employment that Women Face in Egypt: Policy Challenges and Considerations, RAND Corporation.

El-Kogali, SET, and C Krafft (2015) Expanding Opportunities for the Next Generation: Early Childhood Development in the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.