In a nutshell

In the aftermath of disasters, breakdowns in infrastructure and specifically failures of basic hygiene, sanitation and/or running water systems, leave populations susceptible to elevated health risks from disease outbreaks.

Disease outbreaks in low and middle-income countries are the main determinant of weakened improvements in maternal mortality and a key determinant of child mortality. Addressing avoidable maternal and child mortality is paramount in disaster mitigation.

Health emergency management – surveillance, response, preparedness, risk communication, etc. – policies can partially absorb the negative effects of health disasters on maternal and child mortality.

During disease outbreaks, surging demand for healthcare to care for the affected, deaths and illness among health providers, destruction of health facilities and disruption of electricity, water and sanitation, and supply chains inevitably jeopardise the provision of routine health services (Kruk et al, 2016).

Depletion and diversion of resources providing routine primary care occurred during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (2014-16) and the Covid-19 pandemic is likely to lead to similar effects. Such testing of the resilience of a nation’s healthcare system disproportionately affects pregnant women and children during and in the aftermath of disasters (Harville et al, 2010).

The current pandemic began at a time when low and middle-income countries (LMICs) had achieved improved maternal and child health, with a 38% drop in maternal mortality and child mortality halved between 2000 and 2018 (WHO, 2020). Yet with less than a decade left to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), progress toward SDG3 – ‘Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’ – has been uneven.

Particularly relevant is the recommendation by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) Report 2019, which asserts directly that strengthening preparedness for health emergencies becomes more urgent as health disasters continue to erode recent gains (GPMB, 2019).

Health impact of disease outbreaks

The United Nations’ Independent Accountability Panel (IAP, 2020) released concerning figures about the impact of the pandemic in January to April 2020:

- First, women, children and adolescents lost access to 20% of health and social services as a result of the pandemic.

- Second, about 13.5 million children missed life-saving vaccinations over the first four months of 2020; such skipping is particularly dangerous in LMICs.

- Third, before the pandemic, approximately 295,000 women died during or shortly after pregnancy in 2017.

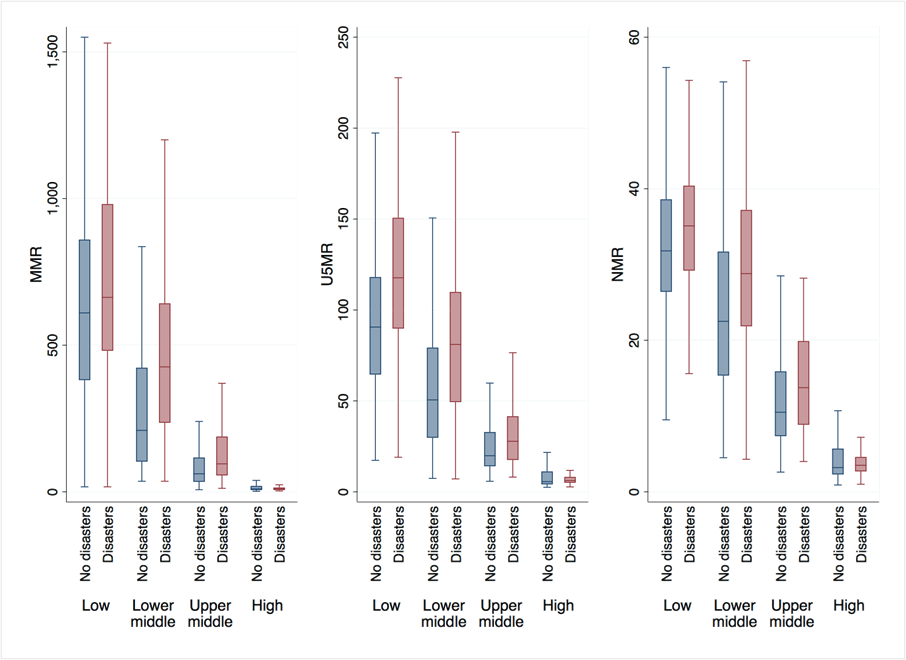

Our recent research, covering 111 countries between 2000 and 2019, of which we consider 93 to be LMICs, suggests that health disasters, in general, have a strong detrimental effect on key health outcomes, specifically maternal mortality ratio (MMR), under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) and neonatal mortality rate (NMR) – see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Maternal mortality, under-5 mortality and neonatal mortality by health disaster occurrence, 2000-19

Note: The figure displays the distribution of maternal mortality ratio (MMR, modelled estimate, per 100,000 live births), under-5 mortality rate (U5MR, per 1,000 live births) and neonatal mortality rate (NMR, per 1,000 live births). The box indicates the interquartile range (the 25th and 75th percentile) and the median. The whiskers indicate the upper and lower values within 1.5 times the interquartile range beyond the 25th and 75th percentiles. Outliers beyond those limits are excluded.

Source: Authors’ computations based on the United Nations Global SDG Indicators database.

The effect is exacerbated in LMICs. Our data show that MMR, U5MR and NMR are, respectively, 14%, 27% and 9% higher on average in low-income countries that experienced health disasters compared with those where no disasters occurred.

The heterogeneity is worse in middle-income countries. In lower-middle income countries, MMR, U5MR and NMR are, respectively, 60%, 42% and 21% higher on average in disaster-hit countries compared with unaffected countries. In upper-middle income countries, MMR, U5MR and NMR are, respectively, 47%, 27% and 19% higher in disaster-hit countries compared with unaffected countries.

Our formal investigation further confirms that health disasters have strong detrimental contemporaneous and long-run effects on maternal and child mortality. In LMICs, health disasters increase maternal, under-5 and neonatal mortalities by, respectively, 0.3%, 0.3% and 0.2% instantaneously.

The magnitude of the long-run effects is much larger. Our estimates indicate that health disasters increase maternal, under-5 and neonatal mortalities by 35%, 80% and 26% after one year, respectively.

How do these results compare with the effects of other determinants of mortality? These determinants include economic status (GDP per capita), health (physician density per 1,000 people, adolescent fertility rate and percentage of births attended by skilled healthcare staff) and education (female primary education completion rate).

We find that the magnitude of the negative impact of health disasters on MMR is the highest and the most significant. But it is GDP per capita, which reflects the economic status of each country, that has the highest impact on under-5 and neonatal mortalities.

This provides novel evidence that over the last two decades, disease outbreaks can be considered the main determinant of the surge or the weakened improvement in maternal mortality and one of the effective determinants of child mortality.

These and other statistics emphasise that addressing avoidable maternal and child mortality is paramount in disaster mitigation.

Mitigating disease outbreaks

Our research shows that healthcare system, macroeconomic, institutional and structural characteristics can mitigate disaster effects.

For example, the stronger the preparedness of healthcare systems, the weaker we anticipate the negative impact of health disasters. The Global Health Security (GHS) index, which assesses and benchmarks health security and related capabilities to prevent and mitigate epidemics and pandemics across 195 countries, shows that sub-Saharan Africa is the least prepared region, with an average score of 31 (out of 100) – see Figure 2.

The heatmap reveals that the Middle East and North Africa region is the second least prepared, with an average score of 36. For South Asia, the average score is 37, in Latin America and Caribbean, 38, in East Asia and Pacific, 40, in Europe and Central Asia, 52 and in North America, 79.

Estimating the role of public health emergency preparedness in mitigating disaster effects, we find that the healthcare system’s capacity to detect, assess, notify, report and respond to public health emergencies significantly mitigates health disaster effects, especially on maternal and under-5 mortalities.

Preparedness is the core system capacity with the highest effect. In LMICs, an increase in the preparedness index by 1 unit is associated with 0.3, 0.1 and 0.01 decrements in the impact of a health disaster on maternal, under-5 and neonatal mortality, respectively.

Risk communication comes second, with an increase in its index by 1 unit being associated with 0.2 and 0.05 decrements in the impact of a health disaster on maternal and under-5 mortalities, respectively.

But we confirm that while public health emergency management plays a significant role in preventing disaster effects, other mitigators, namely health emergency finance, universal health coverage (UHC), education, gender equality and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) coverage, have greater impact.

Figure 2: Global Health Security (GHS) index, 2019

Note: Index ranges from 1 to 100, with higher values indicating better health security conditions.

Source: GHS index database.

GDP per capita comes first as the main mitigator of disaster effects, surpassing all sources of domestic and international health emergency finance in LMICs (official development assistance (ODA), personal remittances and national savings). A 1% increase in a country’s GDP per capita can absorb the disaster effect on maternal, under-5 and neonatal mortalities by 26%, 5% and 0.4%, respectively.

Countries with lower GDP per capita typically face greater difficulty in dealing with disasters due to budgetary restrictions; a government that is cash strapped can hardly mobilise resources to respond to disease outbreaks.

In this context, two results are worth noting:

- Financial inclusion significantly mitigates the disaster effect on maternal and under-5 mortality.

- Channelling resources through remittances significantly mitigates the disaster effect on under-5 mortality.

Healthcare system-related factors come second after GDP per capita as key mitigators of disaster effects. An intuitive result is the significant mitigating effect of physician density on mortality in all settings. In LMICs, an increase in the UHC index by 1 unit is associated with 4.2 and 0.7 decrements in the health disaster effect on maternal and under-5 mortality, respectively.

Education and gender equality come in third place. An increase in the gender parity index by 1 unit is associated with 2, 0.5 and 0.02 decrements in the impact of a health disaster on maternal, under-5 and neonatal mortality, respectively.

Pointing in the same direction, an increase in the women, business and the law index by 1 unit is associated with 1, 0.2 and 0.02 decrements in the impact of a health disaster on maternal, under-5 and neonatal mortality, respectively.

Moreover, an increase in female primary education completion rate by 1% is associated with 1% and 0.03% decrements in the impact of a health disaster on maternal, under-5 and neonatal mortality, respectively.

Estimating the disaster mitigating effects of WASH coverage, we find that increasing access to safe drinking water, safely managed sanitation and basic handwashing facilities by 1% absorbs the adverse effect of disasters on maternal mortality by almost 1%. Drinking water and sanitation appear to have a significant mitigating effect on under-5 mortality, while handwashing has a greater effect on neonatal mortality.

Conclusions and policy implications

The findings of our research provide crucial knowledge that should guide future interventions.

First, health emergency management (surveillance, response, preparedness, risk communication, etc.) policies can partially absorb the negative effects of health disasters on maternal and child mortality in LMICs. Epidemic and pandemic preparedness especially can have substantially high returns through developing public health emergency response plans. Sustained investments in health emergency preparedness will improve health outcomes, build community trust and reduce poverty, thereby contributing to efforts to achieve the SDGs (GPMB, 2019).

Second, creating UHC systems is a priority investment during Covid-19 and beyond. Moving toward UHC can address barriers to healthcare access and alleviate any undue financial burden, with spillover effects on healthcare system resilience to health disasters. Integration of core public health functions into a healthcare system based on primary healthcare with UHC is a pre-condition for preparedness (GPMB, 2020).

Third, improving female education helps make people resilient to shocks and better cope with stresses these shocks bring; this strengthened resilience lessens the direct and indirect impact of disasters on health and wellbeing. Gender equality is an important factor in disaster mitigation efforts. More unequal societies tend to have fewer resources allocated to mitigation as they are unable to resolve the collective action problem of implementing mitigating measures.

Fourth, strengthening the financial infrastructure that supports financial inclusion and remittances can be of particular relevance to mitigating a disaster effect on child mortality.

Finally, the heterogeneity in health infrastructure between countries matters for controlling and mitigating the effect of disease outbreaks. In the aftermath of disasters, especially in LMIC settings, breakdowns in infrastructure and specifically failures of basic hygiene, sanitation and/or running water systems, leave populations susceptible to elevated health risks from disease outbreaks.

Further reading

El-Shal, A, M Mohieldin and E Moustafa (2021) ‘Can disaster preparedness change the game? Mitigating the health impact of disease outbreaks’.

Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) (2019) ‘A world at risk: Annual report on global preparedness for health emergencies’.

Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) (2020) ‘A world in disorder: Annual report on global preparedness for health emergencies’.

Harville, E, X Xiong and P Buekens (2010) ‘Disasters and perinatal health: A systematic review’, Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 65(11): 713-28.

IAP, Independent Accountability Panel for Every Woman Every Child Every Adolescent (2020) ‘Caught in the COVID-19 storm: Women’s, children’s, and adolescents’ health in the context of UHC and the SDGs’.

Kruk, ME, S Kujawski, CA Moyer, RM Adanu, K Afsana, J Cohen et al (2016) ‘Next generation maternal health: External shocks and health-system innovations’, The Lancet 388(10057): 2296-2306.

WHO, World Health Organization (2020) World Health Statistics 2020, May 2020.