In a nutshell

Understanding the facts about inter-religious inequality in Egypt in the pre-colonial and colonial periods – and how it was altered by postcolonial public policies – is of the utmost importance for an informed public debate on the topic.

The Middle East possesses exceptionally detailed microdata sources on inter-religious socio-economic inequality, which can help to document the evolution of inequality and socio-economic differences across sub-denominations within the same religious group.

In Egypt, the population censuses that extend from 1848 through to 2016 provide an extraordinary microdata source that allows the examination of occupational and educational inequality across groups over time.

Socio-economic inequality across religious groups has been at the centre of public debate in the Middle East for decades. Inter-religious tensions between local non-Muslim minorities and the Muslim majority, and across sub-denominations within Muslims and non-Muslims, were among the major sources of social segmentation throughout the history of the region, reaching the level of civil war in Lebanon over the period from 1975 to 1990.

Such tensions were often ignited by inter-religious conflicts over the distribution of political power and economic sources, and they have made the democratic transition of the region extremely challenging.

Yet understanding the current inter-religious inequality in the region arguably requires a longer historical perspective. Inequality is not simply a consequence of postcolonial policies but rather has colonial and, perhaps more importantly, pre-colonial roots.

But scholarship on the economic and social history of the region in general has been lagging behind its counterparts in North America, Western Europe and even other parts of the developing world such as Asia and Latin America – and scholarship on inequality is no exception.

To be sure, it has been long documented in economic history research that local non-Muslim minorities of the Middle East, including Christians and Jews, enjoyed better socio-economic outcomes in terms of educational and occupational attainment than the Muslim majority. But this body of evidence was, for the most part, qualitative, and it lacked a long-run and detail-oriented perspective that documents the evolution of inequality over time and the socio-economic differences across sub-denominations within the same religious group.

Perhaps due to the sensitivity of the topic and a general ‘perceived’ lack of data sources within both academic and non-academic circles, the basic facts on inter-religious socio-economic inequality have been mostly lacking and were thus left to mere speculation.

Issues as simple as the population share of non-Muslims are often considered taboo. In Egypt, the most populous country in the region, a widely circulated figure of non-Muslims’ population share is 10%, but, to the best of my knowledge, the figure is based on an unknown data source, and apparently is mere speculation.

Nevertheless, contrary to widespread belief, the Middle East possesses an exceptionally long and detailed series of microdata sources on inter-religious socio-economic inequality. In Egypt, the population censuses that extend from 1848 through to 2016 provide an extraordinary microdata source that allows examination of occupational and educational inequality across groups over time.

In Saleh (2015), I provided quantitative evidence on this phenomenon by drawing on a unique data source: two nationally representative, individual-level samples of Egypt’s population census manuscripts of 1848 and 1868 that I digitised with the help of a data entry team at the National Archives of Egypt in 2009-10 (Saleh 2013).

Conducted under Muhammad Ali Pasha, the autonomous Ottoman viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1848, and his grandson Ismail (who reigned from 1863 to 1879), these two censuses are among the earliest pre-colonial population censuses from any non-Western country to include information on all segments of the society, including women, children and slaves.

The census samples reveal that Egypt’s non-Muslims constituted 7% of the population in each of 1848 and 1868. The vast majority of Egypt’s non-Muslims were Coptic Christians (94%), followed by non-Coptic Christians such as Levantines, Greeks and Armenians (4%), and Jews, both Rabbinic and Karaite (2%).

The population share of non-Muslims in the 1848 and 1868 samples is consistent with the subsequent village-level population censuses between 1897 and 1996 and the individual-level population census samples from 1986, 1996 and 2006, albeit with important fluctuations over time.

Notably, there was a temporary surge in non-Muslims’ population share between 1868 and 1947, which was likely to have been due to the influx of Levantine Christians, Armenian, Greek and European immigrants into Egypt, followed by a steady yet slow decline in the second half of the 20th century.

Perhaps more importantly, non-Muslims in 1848 and 1868 were more likely than Muslims to work in white-collar occupations and had higher school enrolment rates. But there were significant occupational differences among non-Muslims: non-Coptic Christians had the highest share of white-collar workers, followed by Jews and Coptic Christians. And whereas non-Coptic Christians and Jews were over-represented in commerce and finance, Copts excelled in state fiscal bureaucracy and artisanship.

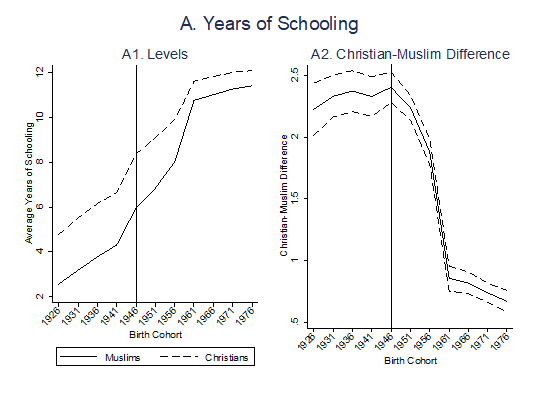

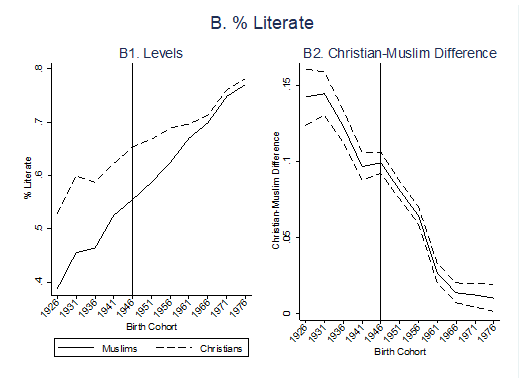

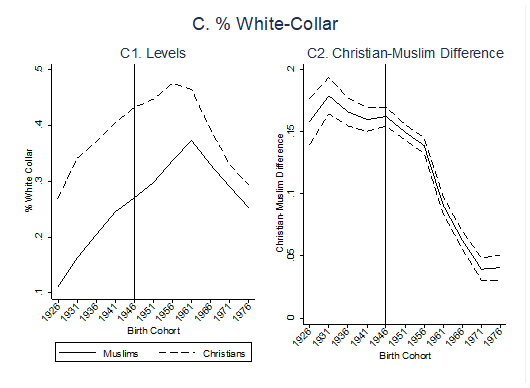

In Saleh (2016), I follow the inter-religious socio-economic gap in the subsequent population censuses during the period from 1897 to 2006, and the individual-level population census samples in 1986, 1996 and 2006 – see Figure I.

The censuses reveal that the gap persisted through the mid-20th century, but it fell towards the end of the century. The reasons for the persistence and the decline of the gap arguably have to do with the growth of European ‘modern’ schools, in which non-Muslim students were over-represented through the 1940s, and the following expansion of public mass primary education between 1951 and 1953, which improved Muslims’ lot vis-à-vis Christians.

The policy of guaranteed employment in the public sector for secondary schools and university graduates that lasted from 1961 until 1983 played a role in occupational convergence. But the occupational gap, measured by the proportion of white-collar workers, did not disappear, probably because of the abolition of the guaranteed employment scheme.

Examining the educational gap in more depth shows that there are persistent important inter-religious differences in specialisation among university students, where Christians are more likely to select into medicine, pharmaceutics and engineering. Muslims on the other hand have traditionally monopolised the high state bureaucracy positions, as well as the judiciary, the military and the police.

Understanding the facts about inter-religious inequality in both the pre-colonial and colonial periods and how it was altered by postcolonial public policies is of utmost importance if we are to have an informed public debate on the topic in the future.

Figure I. Educational and occupational attainment by religion and cohort of birth

Further reading

Saleh, M (2016) ‘Public Mass Modern Education, Religion, and Human Capital in Twentieth-Century Egypt’, Journal of Economic History 76(3): 697-735.

Saleh, M (2015) ‘The Reluctant Transformation: State Industrialization, Religion, and Human Capital in Nineteenth-Century Egypt’, Journal of Economic History 75(1): 65-94.

Saleh, M (2013) ‘A Pre-Colonial Population Brought to Light: Digitization of the Nineteenth-Century Egyptian Censuses’, Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 46(1): 5-18.