In a nutshell

The fiscal and monetary policies implemented in Egypt during the first half of 2020, along with the emergency support provided by international financial institutions, are so far helping the country weather the shock.

Private sector firms do not appear to have experienced problems with access to finance due to Covid-19.

The support of international financial institutions was necessary, but without complementary efforts by local policy-makers, such support would not have been channelled to the real economy.

The Egyptian economy proved resilient to the immense human and financial costs caused by the global pandemic. This resilience may be explained by the implementation of the economic reform programme since 2016, which provided more fiscal space to withstand the adverse impact of the Covid-19 crisis. The fact that the Egyptian economy is holding up is also due to the rapid responses to limit the impact of the virus that were implemented by the government from early 2020.

Moreover, the role played by international financial institutions helped Egypt during the pandemic. These actions enabled the country to avoid a full lockdown policy in 2020. Analysis of data from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys highlights that private sector firms in Egypt did not express financial concerns due to Covid-19.

The pandemic has drastically disrupted people’s lives, livelihoods and economic conditions in Egypt. The global shock has resulted in a tourism standstill (Djankov, 2020), significant capital flight (Djankov and Panizza, 2020) and a slowdown in remittances (Nonvide, 2020), resulting in an urgent balance of payments need.

Egypt responded to the crisis with a comprehensive package aimed at tackling the health emergency and supporting economic activity. The Ministry of Finance acted swiftly to allocate resources to the health sector, to provide targeted support to the most severely affected sectors and to expand social safety net programmes to protect the most vulnerable.

Similarly, the Central Bank of Egypt adopted a broad set of measures, including lowering the policy interest rate and postponing repayments of existing credit facilities (Haidar, 2021). A key issue is the experience of firms following these policies. The following draws on evidence from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys conducted in Egypt between December 2019 and July 2020.

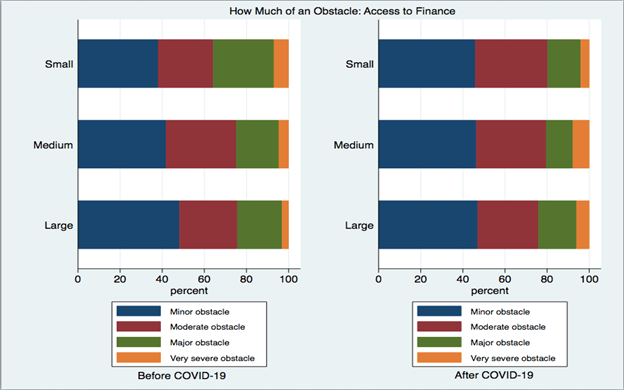

Figure 1a shows that in assessing the degree to which access to finance was an obstacle to business activity, around two-fifths of small firms surveyed before Covid-19 considered it a minor obstacle; around a fifth considered it a moderate obstacle; around a fifth considered it a major obstacle; and around 10% considered it to be a very severe obstacle.

Source: Author’s calculations using World Bank Enterprise Surveys data

This distribution of sentiment more or less held for medium-sized and large firms surveyed before Covid-19, albeit with some adjustments to reflect progressively positive sentiments as firm size increased from medium to large. After Covid-19, firms seemed to adjust their attitudes such that small, medium-sized and large firms were all equally as likely to conceive of access to finance as a minor or moderate obstacle.

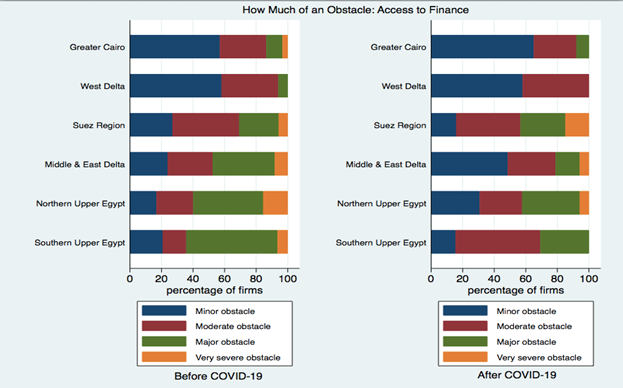

Moreover, access to finance did not seem a major obstacle for firms before or after Covid-19 across geographical regions in Egypt. Figure 1b shows that for firms surveyed before Covid-19 and in the Greater Cairo and West Delta regions, access to finance was overwhelmingly conceived of as a minor or moderate obstacle.

Source: Author’s calculations using World Bank Enterprise Surveys data

For firms surveyed before Covid-19 and in Northern Upper Egypt and Southern Upper Egypt, less than a fifth of firms perceived access to finance as a minor obstacle, and nearly half of the firms cited access to finance as a moderate or major obstacle; this also roughly held for the Suez Region and the Middle and East Delta.

For firms surveyed after the onset of Covid-19, and in the Middle East and Delta region, nearly half of the firms cited access to finance as only a minor obstacle when surveyed after the pandemic, compared with only a fifth sharing the sentiment when surveyed before the pandemic.

Firms in the Northern Upper Egypt region showed some improvements along the same lines, while firms in the Southern Upper Egypt region were much more likely to cite access to finance as a moderate obstacle when surveyed after the pandemic, as opposed to citing it as a major obstacle when surveyed before the pandemic.

In general, perceptions of access to finance seemed to have improved in most regions, except for the Suez region, where perceptions of access to finance seemed to have worsened, with nearly a fifth of firms surveyed after the pandemic in the region perceiving access to finance as a very severe obstacle.

For medium-sized and large firms, the median share of total annual sales paid for after delivery for firms surveyed after the onset of Covid-19 was larger than the median share of total annual sales paid for after delivery for firms surveyed before the onset of Covid-19. For small firms, the medians in both time periods were fairly similar.

Moreover, for small and medium-sized firms, the median share of working capital borrowed from banks for firms surveyed before the onset of the pandemic was similar to the median share for firms surveyed after the onset of the pandemic. For large firms, however, the median share for firms surveyed after the pandemic was nearly 10% higher than for those surveyed before the pandemic.

Most firms, regardless of location and time of survey, reported not having a loan or line of credit because the firm did not apply, not because last application was turned down. This result did not change when dividing firms by industry or size groups, too.

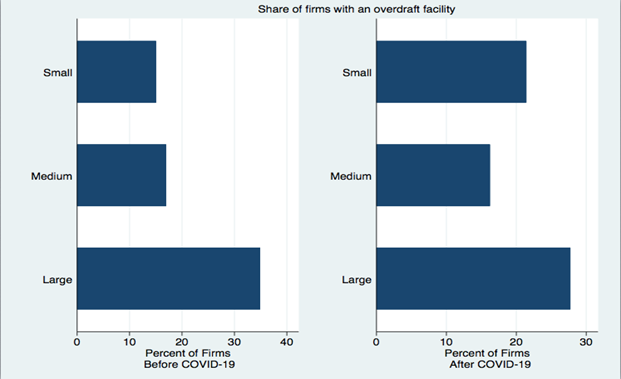

Moreover, prior to the onset of Covid-19, large firms were more likely than medium-sized firms to have overdraft facilities, and in turn, medium-sized firms were more likely than small firms to have overdraft facilities. After the onset of Covid-19, however, the share of firms having overdraft facilities increased in all (small, medium-sized and large) firm-size groups (Figure 2).

Regardless of firm size, the share of firms applying for new loans or lines of credit prior to the onset of the pandemic appeared to be modest. In general, large firms seemed to be more likely to apply for new loans and lines of credit than medium-sized firms, and in turn, medium-sized firms were more likely to apply than small firms.

This pattern loosely held post-pandemic, with medium-sized firms more likely to apply for loans and new lines of credit than small firms, but equally as likely to apply as large firms (Figure 3). Most firms, regardless of size, cite the lack of need for a loan as the main reason for not applying to new loans. This sentiment held for firms surveyed before and after the onset of the pandemic.

The above statistics show that firms did not appear to experience access to finance hurdles due to Covid-19. The support of international financial institutions was necessary, but without complementary efforts by local policy-makers, such support would not have been channelled to the real economy.

Haidar (2021) presents the roles that were played by the Egyptian Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank of Egypt during the pandemic. The fiscal and monetary policies implemented during the first half of 2020, along with the emergency support provided by international financial institutions, are so far helping Egypt weather the shock.

This column has highlighted how private sector firms in Egypt perceived ease of access to finance before and after Covid-19 in 2020. More analysis is needed to understand how firms can expand and create higher quality jobs in Egypt in the presence of the pandemic in the days ahead.

This column is based on ‘How Did Egypt Soften the Impact of Covid-19?’, in Shaping Africa’s Post-Covid Recovery edited by Rabah Arezki, Simeon Djankov and Ugo Panizza, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), 2021.

The World Bank Enterprise Surveys covered a total of 3,075 firms between December 2019 and July 2020 in Egypt.

The survey covered seven regions in Egypt: Greater Cairo, West Delta, Suez Region, Middle and East Delta, Northern Upper Egypt, Southern Upper Egypt.

It spanned firms from 15 industries: Food and Beverages; Textiles and Garments; Leather products; Chemicals and Chemical products; Petroleum products, Plastics and Rubber; Non-metallic mineral products; Basic Metals and Metal products; Machinery, Equipment, Electronics, and Vehicles; Wood products; Furniture, Paper, and Publishing; Other Manufacturing; Construction; Wholesale; Retail and Automotive trade; and Hospitality and Tourism.

It also represented small firms (those with between five and 19 employees), medium-sized firms (20-99 employees) and large firms (100 or more employees).

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah, Simeon Djankov and Ugo Panizza (2021) Shaping Africa’s Post-Covid Recovery, CEPR ebook, summarised at The Forum.

Djankov, Simeon (2020) ‘Reviving tourism in the COVID era: bungs, tax cuts and no more tour buses’, LSE Blog.

Djankov, Simeon, and Ugo Panizza (2020) COVID-19 in Developing Economies, CEPR ebook.

Haidar, Jamal Ibrahim (2021) ‘How Did Egypt Soften the Impact of Covid-19?’, in Shaping Africa’s Post-Covid Recovery edited by Rabah Arezki, Simeon Djankov and Ugo Panizza, CEPR ebook.

Nonvide, G (2020) ‘Policy for limiting the poverty impact of COVID-19 in Africa’, in COVID-19 in Developing Economies edited by Simeon Djankov and Ugo Panizza, CEPR ebook.