In a nutshell

Iran’s middle class – those earning $11-110 a day – has grown over most of the past 50 years. A major exception was the periods coinciding with the revolutionary and immediate post-revolutionary turmoil and the Iran-Iraq war.

The most important channels through which oil rents affect the size of the middle class in Iran are imports, the service sector (including public sector) and overall economic development.

An increase of 35% in oil income per capita leads to an increase of 4% in the size of the middle class share of the population three years after the initial shock. Middle class enlargement is not associated with improvements in the quality of political institutions.

The significance of the middle class in relation to economic development and industrialisation has been underscored by much research as both a driving force and a key consequence of development (for example, Persson and Tabellini, 1994; Easterly, 2001; Banerjee and Duflo, 2008; Kharas and Gertz, 2010).

Given such middle-class preferences as accumulation and stability, a positive relationship between its expansion and political development has also been highlighted (for example, Loayza et al, 2012). Studies probing the development of industrial capitalism and modern democracy in Western Europe and North America (such as Chen and Lu, 2011) have largely described a relationship running from the former to the growth of the middle class and then to the latter.

Reflections on the relationship between the growth of the middle class and political development have been much more qualified in research concerned with late industrialisers and other developing countries (such as Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012). Positive political outcomes have been associated with conditions that are not easily attainable – for example, when the middle class has political cohesion, is not tied down by immediate economic worries or future political instability, and is independent enough from the state.

Concerning the latter, the political establishment may succeed in controlling private economic activities and employ a large number of people to shape the middle class as a state class (Elsenhans, 1996). Such circumstances have been described for the case of the middle classes in Middle Eastern countries (Diwan, 2013; Bjorvatn and Farzanegan, 2013).

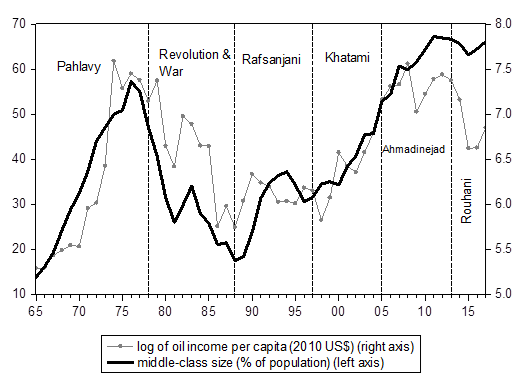

Iran’s middle class has experienced persistent expansion since the 1960s, excluding the period coinciding with the revolutionary and immediate post-revolutionary turmoil and the Iran-Iraq war. This growth appears to have been influenced by the country’s oil income (see Farzanegan and Markwardt, 2009; Farzanegan and Alaedini, 2016; Farzanegan and Habibpour, 2017). This is shown by the co-movement of the middle class size and oil receipts in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Iran’s middle class as a percentage of total population and oil income per capita

Note: Middle-class variables estimate and provide forecasts of the number of people living in households earning or spending between $11 and $110 per person per day (2011 $ purchasing power parity (PPP) prices) and are taken from Kharas (2017).

The Iranian middle class had grown to more than half of the population a few years before 1979. Yet it appears to have been negatively affected shortly before the revolution, which might have contributed to its dissatisfaction with the previous regime. The middle class shrank gradually but significantly during the 1980s as a result of economic turmoil and stalled growth exacerbated by an oil slump and the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88).

The size of the middle class shrank to its lowest level in the late 1980s. A relatively large number of white-collar government employees were fired, bought out or retired in the same period. Yet they were eventually replaced by the revolutionary cadre, who might have experienced upward mobility from the lower to the middle class.

Once the war ended, the size of the Iranian middle class began to recover. It grew slowly during Mr Rafsanjani’s presidential terms (1989-97) and the post-war reconstruction activities. This expansion gained additional speed during Mr Khatami’s presidential tenure (1997–2005), probably as a result of reduced economic instability, higher rates of economic growth and a degree of political openness affecting the opportunities of the civil society and the middle class. Urbanisation and increased access to urban services also continued to expand in this period.

By the end of Mr Khatami’s second term in office, Iran’s middle class again comprised about half of the total population. It continued to grow through most of Mr Ahmadinejad’s populist presidential tenure (2005-13) and the ensuing oil boom. Yet the trend seems to have stalled after 2011 – which is likely to be due to the intensification of sanctions as well as economic mismanagement and more recently an oil price slump.

That said, the declining trend was halted in 2016-17 under Mr Rouhani’s administration in association with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (an agreement reached in 2015 between Iran and the permanent members of United Nations Security Council plus the European Union and Germany), which temporarily reduced the international sanctions imposed on the Iranian economy.

These observations call for a rigorous analysis of the relationships between oil revenues, the size of the middle class and political development in Iran. In a recent study, we examine the effect of oil revenues on the absolute as well as relative measures of the middle class, the transmission channels of the impacts, and the consequences in terms of political development (Farzanegan et al, 2021).

Using annual data from 1965 to 2017, we have tested the following hypothesis: the response of Iran’s middle-class size to positive oil-income shocks is positive, ceteris paribus. We control for possible transmission channels by considering per capita GDP, per capita imports, private sector investment in urban areas, total fertility rate and the quality of political institutions. We also control for Iran’s 1979 revolution and its eight-year war with Iraq.

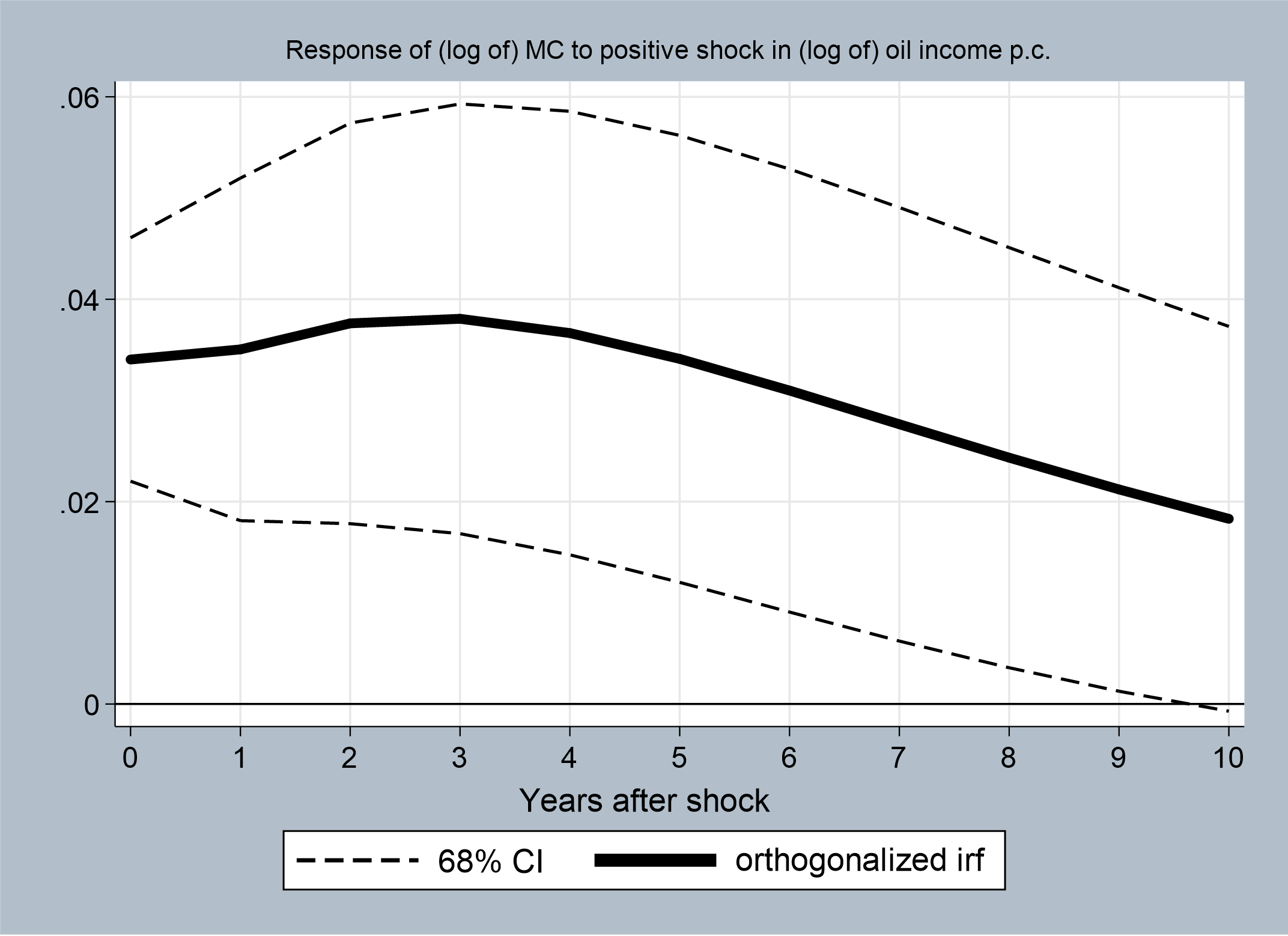

Our main results show a positive response of the size of middle class in Iran to a positive shock in oil rents. Figure 2 indicates that an increase of 35% in oil income per capita leads to an increase of 4% in the size of the middle class share of the population three years after the initial shock.

Figure 2. Response of Iran’s middle class to positive oil income per capita changes. (For Notes, see Farzanegan et al, 2021).

Our study shows that the most important channels through which oil rents may affect the size of the middle class in Iran are imports, the service sector (including public sector) and overall economic development (captured by real GDP per capita). Finally, we show the lack of a significant relationship between the size of the middle class and the quality of political institutions.

Conclusion

Using both absolute and relative measures, our study has examined the effect of oil earnings on the size of the middle class in Iran. While Iran’s middle class has experienced a number of ups and downs over the past 50 years, it has continued to grow since the end of the war with Iraq in 1988.

According to our findings, the response of the middle class to positive oil shocks is positive and significant. This is to be expected, as many in the middle of the society benefit from the country’s oil income. The main transmission channels between oil-income shocks and the size of the middle class in Iran are imports, the service sector, and the overall economic development.

The simulation analysis has not shown any significant interaction between the middle class and the quality of political institutions. This is likely to be due to the significant dependence of this part of society on the government’s distribution of oil rents.

Further reading

Acemoglu, D, and J Robinson (2012) Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, Crown.

Banerjee, A, and E Duflo (2008) ‘What is middle class about the middle classes around the world?’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 22: 3-28.

Bjorvatn, K, and MR Farzanegan (2013) ‘Demographic transition in resource rich countries: a bonus or a curse?’, World Development 45: 337-51.

Chen, J, and C Lu (2011) ‘Democratization and the middle class in China: The middle class’s attitudes toward democracy’, Political Research Quarterly 64: 705-19.

Diwan, I (2013) ‘Understanding revolution in the Middle East: The central role of the middle class’, Middle East Development Journal 5.

Easterly, W (2001) ‘The middle class consensus and economic development’, Journal of Economic Growth 6: 317-35.

Elsenhans, H (1996) State, Class, and Development, Radiant Publishers.

Farzanegan, MR, and P Alaedini (eds) (2016) ‘Economic Welfare and Inequality in Iran: Developments since the Revolution’, Palgrave Macmillan/Springer Nature.

Farzanegan, MR, P Alaedini, K Azizimehr and MM Habibpour (2021) ‘Effect of oil revenues on size and income of Iranian middle class’, Middle East Development Journal (in press).

Farzanegan, MR, and MM Habibpour (2017) ‘Resource rents distribution, income inequality and poverty in Iran’, Energy Economics 66: 35-42.

Farzanegan, MR, and G Markwardt (2009) ‘The effects of oil price shocks on the Iranian economy’, Energy Economics 31: 134-51.

Kharas, H (2017) ‘The unprecedented expansion of the global middle class: An update’, The Brookings Institution.

Kharas, H, and G Gertz (2010) ‘The new global middle class: A cross-over from West to East’, in C Li (ed.) China’s Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation, Brookings Institute Press.

Loayza, N, J Rigolini and G Llorente (2012) ‘Do middle classes bring about institutional reforms?’, Economics Letters 116: 440-44.

Persson, T, and G Tabellini (1994) ‘Is inequality harmful for growth?’, American Economic Review 84: 600-21.