In a nutshell

The immediate policy priority for the region is to protect the population from the coronavirus: efforts should focus on mitigation and containment measures to protect public health.

Economic policy responses should be directed at preventing the pandemic – a temporary health crisis – from developing into a protracted economic recession with lasting welfare losses to the society through increased unemployment and bankruptcies.

Now, more than ever, international cooperation is vital if we hope to prevent lasting economic scars.

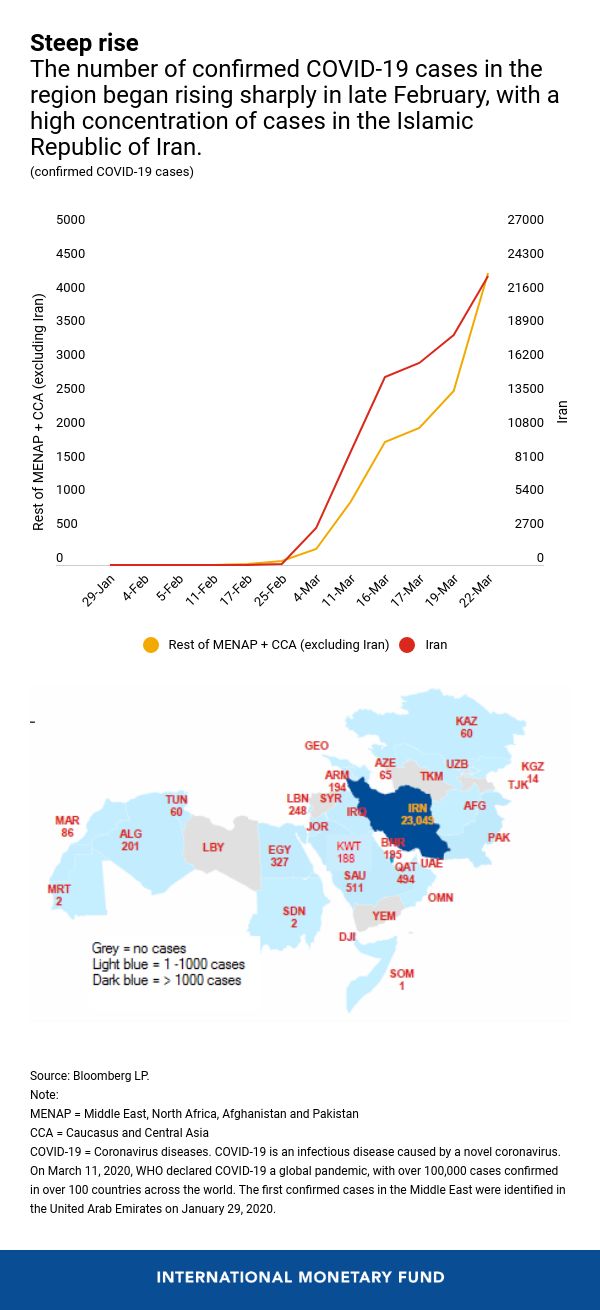

The impact of COVID-19 and the oil price plunge in the Middle East and the Caucasus and Central Asia has been substantial and could intensify. With three-quarters of the countries reporting at least one confirmed case of COVID-19 and some facing a major outbreak, the coronavirus pandemic has become the largest near-term challenge to the region. Like much of the rest of the world, people in these countries were taken utterly by surprise with this development, and I would like to express my solidarity with them as they cope with this unprecedented health crisis.

This challenge will be especially daunting for the region’s fragile and conflict-torn states – such as Iraq, Sudan and Yemen – where the difficulty of preparing weak health systems for the outbreak could be compounded by reduced imports due to disruptions in global trade, giving rise to shortages of medical supplies and other goods and resulting in substantial price increases.

Beyond the devastating toll on human health, the pandemic is causing significant economic turmoil in the region through simultaneous shocks – a drop in domestic and external demand, a reduction in trade, disruption of production, a fall in consumer confidence and tightening of financial conditions.

The region’s oil exporters face the additional shock of plummeting oil prices. Travel restrictions following the public health crisis have reduced the global demand for oil, and the absence of a new production agreement among OPEC+ members has led to a glut in oil supply. As a result, oil prices have fallen by over 50% since the start of the public health crisis. The intertwined shocks are expected to deal a severe blow to economic activity in the region, at least in the first half of this year, with potentially lasting consequences.

Channels of economic impact

Here’s what we know.

First, measures to contain the pandemic’s spread are hurting key job-rich sectors: tourist cancellations in Egypt have reached 80%, while hospitality and retail have been affected in the United Arab Emirates and elsewhere. Given the large numbers of people employed in the service sector, there will be wide reverberations if unemployment rises and wages and remittances fall.

Production and manufacturing are also being disrupted and investment plans put on hold. These adverse shocks are compounded by a plunge in business and consumer confidence, as we have observed in economies around the world.

In addition to the economic disruptions from COVID-19, the region’s oil exporters are affected by lower commodity prices. Lower export receipts will weaken external positions and reduce revenue, putting pressures on government budgets and spilling over to the rest of the economy. Oil importers, on the other hand, will likely be affected by second-round effects, including lower remittance inflows and weaker demand for goods and services from the rest of the region.

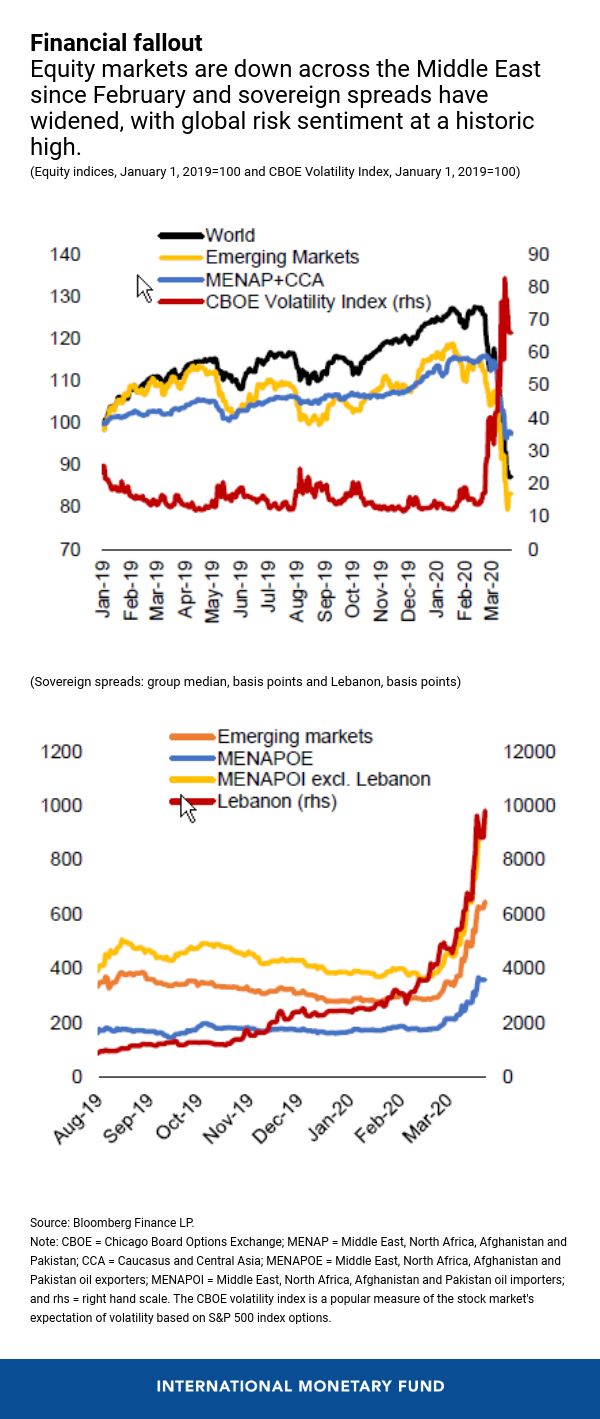

Finally, sharp spikes in global risk aversion and the flight of capital to safe assets have led to a decline in portfolio flows to the region by near $2 billion since mid-February, with sizeable outflows observed in recent weeks – a risk I underscored in a recent blog. Equity prices have fallen, and bond spreads have risen. Such a tightening in financial conditions could prove to be a major challenge, given the region’s estimated $35 billion in maturing external sovereign debt in 2020.

Against this challenging backdrop, the region is likely to see a big drop in growth this year.

Policy priorities

The immediate policy priority for the region is to protect the population from the coronavirus. Efforts should focus on mitigation and containment measures to protect public health. Governments should spare no expense to ensure that health systems and social safety nets are adequately prepared to meet the needs of their populations, even in countries where budgets are already squeezed.

Governments in the Caucasus and Central Asia, for example, are increasing health spending and considering broader measures to support to the vulnerable and shore up demand. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, where the coronavirus outbreak has been particularly severe, the government is ramping up health spending, providing additional funding to its Ministry of Health.

Beyond that overarching imperative, economic policy responses should be directed at preventing the pandemic – a temporary health crisis – from developing into a protracted economic recession with lasting welfare losses to the society through increased unemployment and bankruptcies.

However, the uncertainty about the nature and duration of the shocks has complicated the policy response. Where policy space is available, governments can achieve this goal using a mix of timely and targeted policies on hard-hit sectors and populations, including temporary tax relief and cash transfers.

Temporary fiscal support should consist of measures that provide well-targeted support to affected households and businesses. This support should aim to help workers and firms weather the significant, but hopefully temporary, stop in economic activity that the health measures being implemented to control the spread of the coronavirus will entail.

This support will have to take account of the fiscal space that is available, and where policy space is limited be accommodated by reprioritising revenue and spending objectives within existing fiscal envelopes. Where liquidity shortages are a major concern, central banks should stand ready to provide ample liquidity to banks, particularly those lending to small and medium-sized enterprises, while regulators could support prudent restructuring of distressed loans without compromising loan classification and provisioning rules.

When the immediate crisis from the coronavirus has begun to dissipate, consideration could be given to more conventional fiscal measures to support the economy, such as restarting infrastructure spending, although fiscal space has been significantly eroded over the last decade. Given the nature of the current slowdown, trying to stimulate the economy at this time is unlikely to be successful and would risk eliminating the limited fiscal space that is still available.

Many countries are already introducing targeted measures. For example, several countries – Kazakhstan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, to name a few – have announced large financial packages to support the private sector. These packages include targeted measures to defer taxes and government fees, defer loan payments, and increase concessional financing for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Other countries, particularly the region’s oil importers, have more limited policy space. Lower revenues resulting from lower imports – on top of additional pandemic mitigation spending – are expected to widen fiscal deficits in these economies. And while well-targeted health spending should not be sacrificed, very high debt in many of these oil-importing countries means that they will lack the resources to respond adequately to the broader economic slowdown.

As such, these countries should try to strike a balance between easing credit conditions and avoiding vulnerability to capital outflows, and, where possible, allow the exchange rate to cushion some of the shocks. Sizeable financing needs are likely to arise in some countries.

Support from the IMF

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, we have been in continuous interaction with the authorities in our region to offer advice and assistance, especially those in urgent need of financing to withstand the shocks. The Fund has several tools at its disposal to help its members surmount this crisis and limit its human and economic cost, and a dozen countries from the region have already approached the Fund for financial support.

Work is ongoing to expedite approval of such requests – later this week, our Executive Board will consider a request from the Kyrgyz Republic for emergency financing, likely the first such disbursement since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. A few other requests will be considered by the Executive Board in the coming days. Now, more than ever, international cooperation is vital if we hope to prevent lasting economic scars.

This article was originally published on the IMF Blog. Read the original article here.