In a nutshell

While several vaccines are starting to be commercialised and distributed globally, Africa faces uncertainty over the logistical and financing challenges associated with a large vaccination campaign.

Political leaders in Africa and the advanced economies alike may be underestimating the prospects for a delayed but massive spread of the Covid-19 virus on the continent.

This scenario has to be avoided with decisive policy actions, including the temporary suspension of patents rights for Covid-19 vaccines for poor countries.

With the exception of some flashpoints in Northern and Southern Africa, the continent has been largely spared from the direct health effect of the Covid-19 pandemic. But the African economy has been significantly hurt by the economic consequences of Covid-19, which piled on other continuing calamities such as the locust crisis devastating crops across the continent (Evenett and Baldwin, 2021). Economies in the continent are heavily dependent on commodity exports (Arezki and Fan, 2020), foreign direct investment, remittances, aid as well as tourism – a sector which has been devastated by the pandemic and is unlikely to recover quickly.

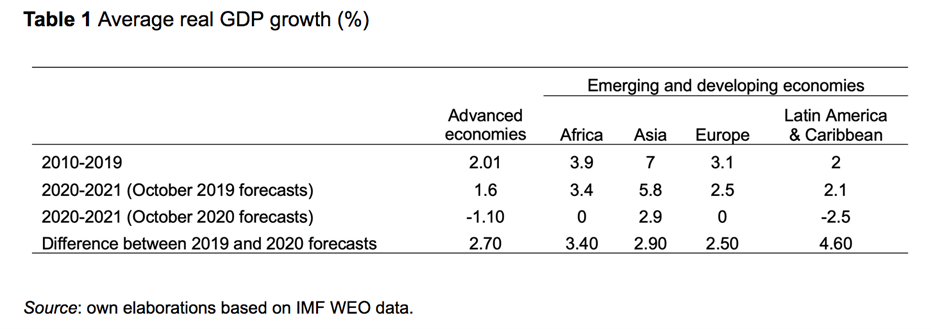

Revised growth forecasts by the African Development Bank and the International Monetary Fund show that Africa is experiencing its first recession in a quarter of a century. Before the explosion of the pandemic, 2020/21 growth was expected to remain close to 3.5%, while the most recent forecasts suggest that the continent will have zero growth over 2020/21. Given the continent’s high population growth, this will lead to a 2.5% contraction in GDP per capita (Table 1).

Table 1 Average real GDP growth (%)

While the impact of the pandemic on GDP growth is similar across world regions (for a discussion of the impact of the pandemic across developing regions, see Djankov and Panizza, 2020), Africa is of particular concern because of its high prevalence of extreme poverty. Recent estimates suggest that the region will be responsible for nearly one-third of the increase in extreme poverty associated with the pandemic (Valensisi, 2020).

A new eBook (Arezki et al, 2021) summarises recent research on the economic effect of the Covid-19 pandemic in Africa covering a wide array of topics focusing on the response of firms, households, governments and international organisations.

Business and household responses

The first part of the eBook focuses on business and household responses. It starts with a comprehensive firm-level analysis by Davies, Nayyar, Reyes and Torres. The authors use surveys conducted by the World Bank Group to study how firms are affected by the pandemic. They find that firms in sub-Saharan Africa report higher degrees of uncertainty and worsened access to government support programmes compared with firms in other emerging economies.

In the second chapter of this section, Djankov and Evans show that there is substantial heterogeneity across firms in Africa. By using simple accounting measures to estimate the share of private manufacturing firms in financial distress under a hypothetical scenario of losing half their sales, they find that larger and older firms tend to be more resilient and that these effects are particularly important in West Africa.

In the next chapter, Byrne, Karpe, Kondylis, Lang and Loeser focus on sectoral heterogeneity. Using high-frequency administrative tax records from Rwanda on firm sales and employment, these authors show that while the initial shock affected sectors in which in-person work was most necessary, the sectors in which face-to-face interactions with consumers are most necessary continue to experience a protracted recovery.

Foreign direct investments (FDI) are a significant source of external finance for many African countries. Chaudhary, Santos-Paulino and Trentini show that the pandemic led to a dramatic decline in FDI flows to Africa as lockdowns slowed existing investment projects and the prospects of a protracted recession led investors to reassess new projects.

Several African economies are characterised by an important presence of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The chapter by Gaspar, Medas and Ralyea suggests that well-run and financially sound SOEs can promote a more inclusive economic recovery. But this positive role of SOEs requires a set of comprehensive reforms aimed at improving the transparency and accountability of SOEs operations and the relationship between SOEs and the government.

Arezki, Froidevaux, Huynh, Nguyen and Salez use big data analysis to explore the effect of the pandemic on tourism in Africa – a sector on which many countries in the continent depend heavily. The authors argue that restarting tourism is a priority for public policy and that investing in travel safety and health standards, including vaccines, will reassure international investors that Africa is open for business.

The last two chapters of this first section focus on households. Furbush, Josephson, Kilic and Michler provide evidence on the evolving socio-economic impacts of the pandemic among households in several African countries. They find that while households are starting to see recovery in income, business revenues and food security, these gains have been relatively modest.

Adjognon, Jeong and Legovini use a panel of household surveys to show that the pandemic did not have a large impact on food security in a group of African countries. The authors argue that a relaxation of lockdown measures and, somewhat in contrast with the results of the previous chapter, a scaling-up of social protection programmes might have offered protection to vulnerable populations and provided a demand stimulus for the rest of the economy.

International financing

The second section of the eBook focuses on access to international finance, patterns in international borrowing and country-specific experiences.

In the first chapter of this section, Arezki explores ways in which international development banks can rethink their role in rebuilding the global economy. He points out that as the balance sheets of multilateral and regional development banks are relatively small compared with the size of the global economy, these institutions quickly encountered limits to their abilities to deploy resources to ameliorate the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Duggan, Morris, Sandefur and Yang compile a new dataset on World Bank lending aimed at comparing the World Bank’s Covid response to its response during the global financial crisis. The authors show that lending commitments have accelerated in 2020, but actual disbursements did not grow by much and that aid remains small relative to the scale of the crisis.

About 20% of public and publicly guaranteed external debt issued by countries in sub-Saharan Africa is owed to China. Brautigam and Acker provide details on the composition of Chinese lending. Chinese loans typically finance infrastructure, with 70% of total lending going to just four sectors: transport, electric power, communications and water.

The pandemic has propelled the issue of debt distress to the forefront of the policy agenda. Bolton, Gulati and Panizza describe Africa’s debt situation and discuss some options for providing temporary legal protection to debtor countries in the event of a global debt crisis.

Hausmann and Goldstein focus on the experience of three countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The authors point out that there are factors that slow down transmission of the infection in poorer countries. But low-income countries cannot rely as much on their healthcare systems when their citizens get sick and their governments have much smaller fiscal space to absorb tax revenue declines or to expand spending in the event of a crisis. The three cases also show the importance of international cooperation, knowledge creation and financial support.

Haidar discusses the case of Egypt, where the pandemic has resulted in a tourism standstill, significant capital flight and a slowdown in remittances. He shows that Egypt responded to the crisis with a comprehensive package aimed at tackling the health emergency and supporting economic activity, but that further steps are needed to tame the virus and return the economy to a growth path.

What’s next?

The world is experiencing another wave of Covid-19 infections. While several vaccines are starting to be commercialised and distributed globally, Africa faces uncertainty over the logistical and financing challenges associated with a large vaccination campaign. COVAX, an international facility, aims at accelerating the production of Covid-19 vaccines and guaranteeing access for every country in the world, with the objective of vaccinating at least 20% of the population of every country by the end of 2021. This 20% target is both ambitious and underwhelming. Ambitious because of the various challenges related to the production, distribution and financing of Covid vaccines; underwhelming because 20% of people vaccinated will not be sufficient to bring back economic activity to pre-crisis levels, even if the target is reached.

Besides the logistical challenges, one key issue relates to the international pricing of vaccines. While a temporary suspension of patents could allow generics to be produced and distributed to developing countries quickly, the global community has so far been unwilling to adopt it.

The slow delivery of vaccination to Africa – and developing countries in general – is worrying. Political leaders in Africa and the advanced economies alike may be underestimating the prospects for a delayed but massive spread of the Covid-19 virus on the continent. Existing data underestimate the prevalence of the disease and the newly found variants of the virus may lead to Africa running into further difficulties.

With the rest of the world taming the disease with concerted efforts, Africa could become the new reservoir. This scenario has to be avoided with decisive policy actions, including the temporary suspension of patents rights for Covid-19 vaccines for poor countries.

Further reading

Arezki, R and R Fan (2020) ‘Oil Price Wars in Time of Covid-19‘, VoxEU.org, 10 March.

Arezki, R, S Djankov and U Panizza (2021) Shaping Africa’s Post-Covid Recovery, CEPR Press.

Djankov, S and U Panizza (2020) COVID-19 in Developing Economies, CEPR Press.

Evenett, S and R Baldwin (2021) ‘Memo to the new WTO Director-General: Never waste a crisis‘, VoxEU.org, 10 February.

Valensisi, G (2020) ‘COVID-19 and global poverty: A preliminary assessment’, in S Djankov and U Panizza (eds), COVID-19 in Developing Economies, CEPR Press.

This column was first published on VoxEU.