In a nutshell

An Egyptian education policy change that reduced compulsory schooling from nine to eight years provided an opportunity to estimate the impact of maternal education on three FGM outcomes: mothers’ attitude, intention to perform, and actual practice.

The evidence indicates that maternal education only has a favourable impact in reducing supportive attitudes towards the practice; this limited protective role could be explained by poor quality schooling and the power of traditionalism versus education.

Reducing school dropout rates and increasing years of schooling could have a beneficial effect in changing attitudes that support FGM.

Female genital mutilation (FGM, also known as female circumcision), defined as partial or total removal of the external genital organ of young girls and women for cultural or non-medical reasons, is a violation of human rights. There is extensive medical evidence that FGM has short-term and long-lasting adverse health effects, both physical and psychological, on circumcised women and their children (Berg and Denison, 2014).

In recognition of the importance of ending FGM, the United Nations has included it as one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets to be achieved before 2030. Target 5.3 of the (SDGs) calls for ‘Eliminating all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation.’

Egypt has the world’s highest number of circumcised women (28 Too Many, 2017). The practice has been a tradition in the country since the Pharaonic period. According to the 2014 Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), around 92% of Egyptian women aged 15-49 had been circumcised.

Statistics also show that Egypt is not on track to reach the SDG target of eliminating FGM. Compared with the rate of decline in the past 15 years, progress would need to be about 15 times faster to stop the practice by 2030 (UNICEF, 2020).

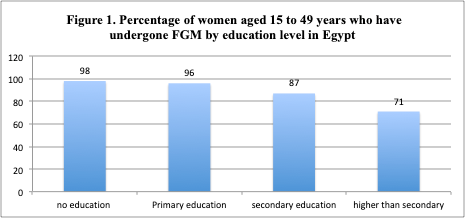

Statistics reveal that the prevalence of FGM is high across many population groups in Egypt. But the practice is more prevalent in rural areas, in less wealthy households, and among girls and women with less education (UNICEF, 2020). Figure 1 displays that FGM is highly prevalent among women with lower levels of education.

Source: UNICEF, 2020.

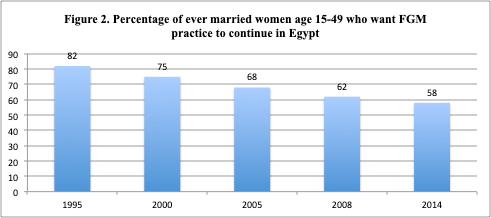

Figure 2 shows a declining trend in ever-married women’s support for the FGM practice where the proportion of women who believe that FGM should continue in the future declined from 82% in 1995 to 58% in 2014. Nonetheless, the percentage of women who support the practice is still substantial.

Source: EDHS, 2014.

Even though FGM is outlawed in Egypt, it is expected that more than half of daughters aged up to 19 will be circumcised in the future based on mothers’ reported intentions (EDHS, 2014).

Article 242 of the Egyptian Penal Code criminalises the act of FGM. According to Law No.126 of 2008, FGM is considered a misdemeanour with a penalty of imprisonment for three months and two years on practitioners who commit the offence.

In 2016, an amendment was undertaken to article 242, strengthening the penalty, in which individuals committing FGM will be punished with a period of imprisonment of between five and seven years. The new amendment extended the punishment to individuals who accompany the victim girls to the perpetrators with imprisonment for between one and three years and up to 15 years’ imprisonment if the practice of FGM leads to the victim’s death or a permanent deformity.

Although FGM is outlawed, there is evidence that the prohibition laws are not adequately enforced. This motivates the search for policy instruments, other than the legal ones, to discourage the practice.

Education has been consistently considered a protective factor that can reduce girls’ exposure to risky health practices such as FGM. There is a substantial body of evidence in epidemiology and public health examining the impact of education on FGM in a non-causal fashion (Dalal et al., 2010; Tamire and Molla, 2013).

Nonetheless, these studies have largely ignored the potential endogeneity of maternal education when examining its impact on FGM, resulting in biased estimates. Their results should be interpreted as correlation rather than causal. Also, although research is abundant with studies investigating the impact of education on the actual practice of FGM, studies that explore the causal impact of education on attitudes toward FGM and the intention to perform FGM remain sparse.

Changes in compulsory schooling legislation are natural policy experiments and are commonly used to instrument education. For example, Dinçer et al (2014) and Güneş (2015) used Turkey’s 1997 education law that increased compulsory schooling from five to eight years to study the effect of maternal education on women’s fertility, reproductive health and empowerment, as well as their children’s health.

Starting from the school year 1988/89, the Egyptian ministry of education reduced the number of years of primary schooling from six to five years, thereby switching to an eight-year instead of a nine-year compulsory education system. All students born on or after 1 October 1977 were exposed to this policy reform in the education system.

Our research uses this exogenous change in the length of compulsory schooling to estimate the causal impact of maternal education on mothers’ attitudes toward FGM, the actual practice of FGM, and their intention to perform FGM on their daughters in the future.

The same education reform that reduced the length of primary school in Egypt has been used by several earlier studies to estimate the causal impact of maternal education on several health and labour market outcomes with mixed findings regarding the effect of education (see, for example, Ali and Elsayed, 2018; Ali and Gurmu, 2018).

We used a representative sample of 16,572 ever-married women aged between 15 and 49 from the 2008 Egypt’s Demographic and Health Survey and a fuzzy regression discontinuity framework to estimate the causal impact of maternal education on the three FGM outcomes; attitude toward FGM; the actual practice of FGM; and the mothers’ intention to perform FGM on their daughters in the future.

The merit of the analytical framework is that it allows us to account for the cohort effect by exploiting a narrower cohort variation in exposure to different compulsory years of education. The identification strategy compares women born just before October 1977 with women born just after this date.

Our results show that maternal education has no statistically significant effect on the actual practice and the intention to perform FGM in the future, while it has a statistically significant positive impact in reducing supportive attitudes towards the practice.

Figure 3 shows women’s attitude toward the continuation of the FGM practice by maternal education level. It is evident that support for the continuation of the practice decreases with the education level.

Source: EDHS, 2014.

A key policy message based on our findings is that reducing school dropout rates and increasing years of schooling could have a beneficial effect in changing attitudes that are supportive of FGM. This would supplement other policy measures implemented to discontinue the FGM practice.

The limited protective role of education in curbing the actual practice of FGM could be explained by the poor quality of schooling in Egypt and the power of traditionalism versus education.

Further reading

Ali, FRM, and MA Elsayed (2018) ‘The effect of parental education on child health: Quasi‐experimental evidence from a reduction in the length of primary schooling in Egypt’, Health Economics 27(4): 649-62.

Ali, FRM, and A Gurmu (2018) ‘The impact of female education on fertility: A natural experiment from Egypt’, Review of Economics of the Household 16(3): 681-712.

Berg, RC, and E Denison (2012) ‘Effectiveness of interventions designed to prevent female genital mutilation/cutting: a systematic review’, Studies in Family Planning 43(2): 135-46.

Dalal, K, S Lawoko and B Jansson (2010) ‘Women’s attitudes towards discontinuation of female genital mutilation in Egypt’, Journal of Injury and Violence Research 2(1): 41.

Dinçer, MA, N Kaushal and M Grossman (2014) ‘Women’s education: Harbinger of another spring? Evidence from a natural experiment in Turkey’, World Development 64: 243-58.

Güneş, PM (2015) ‘The role of maternal education in child health: Evidence from a compulsory schooling law’, Economics of Education Review 47: 1-16.

Sharaf, MF, and AS Rashad (2021) ‘Does Maternal Education Curb Female Genital Mutilation? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper.

Tamire, M, and M Molla (2013) ‘Prevalence and belief in the continuation of female genital cutting among high school girls: a cross-sectional study in Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia’, BMC Public Health 13(1): 1-9.

UNICEF (2020) ‘Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt: Recent trends and projections’.

28 Too Many (2017) ‘Country Profile: FGM in Egypt’.