In a nutshell

Turkey’s manufacturing sectors post faster growth through backward linkages in global value chains, whereas services sectors do so through forward linkages; agricultural sectors have the lowest participation.

There are significant associations between participation in global value chains and employment creation at the sector level in Turkey.

There are significant indirect effects of participation in global value chains on employment for the manufacturing sectors.

Economies’ participation in global value chains (GVCs) is witnessing unprecedented growth. Integration in GVCs occurs principally through the import of intermediate products used in the country’s exports and/or the supply of intermediate products to third countries’ exports. Several economic indicators are influenced by this integration into GVCs with effects depending on the extent of integration.

Previous research has stressed the significant association between international trade, productivity and employment, among other economic outcomes. For example, my recent study uses the world input-output tables to document a significant association between participation in GVCs and labour productivity at the sector level in Turkey (Mohamedou, 2020).

A study by Feenstra and Hanson (1996) links increasing demand for skilled workers with growth in trade in intermediate products. Banga (2016) shows that integration into GVCs is significantly related to employment in India and that increasing imports of intermediate products used in the country’s exports result in a kind of labour displacement at the sector level. Mohamedou and Tengku (2021), report a significant association between backward linkages, domestic value-added exports and employment at the sector level in Japan.

In this column, we shed some light on the importance of international trade in general and trade in value-added, in particular, for employment formation at the sector level in Turkey. Figure 1 shows trends in GVC participation, backward linkages (foreign valued-added export [FVA]), and forward linkages (Indirect value-added export [DVX]), which appear to be growing from 2001 onwards.

Figure 1. GVC participation, backward and forward linkages for Turkey, 2000-14

Source: Mohamedou (2019)

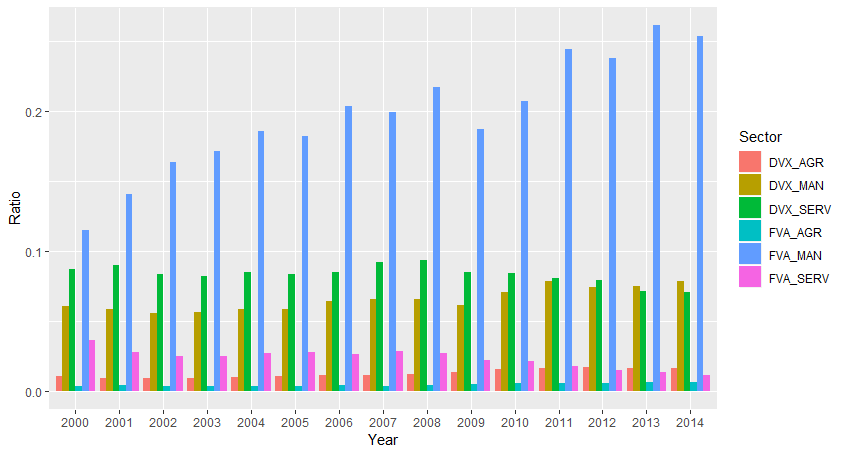

Figure 2 depicts trends in backward and forward linkages for the manufacturing, services, and agricultural sectors in Turkey from 2000 to 2014. The manufacturing sectors post faster growth through backward linkages, whereas services sectors do so through forward linkages. Agricultural sectors have the lowest participation.

Figure 2. Backward and forward linkages change from 2000 to 2014

Source: Mohamedou (2019)

The associations between GVC-related variables and employment in Turkey

Another of my studies analyses the effects of backward and forward linkages on employment for the manufacturing, services and agricultural sectors (Mohamedou, 2019). It shows that backward linkages contribute to the job creation process for manufacturing sectors. This suggests that the imports of intermediate products used in the country’s exports are used in conjunction with domestically produced goods, which stimulate both employment and productivity.

The study also shows that forward linkages are negatively associated with employment in the services sectors. A likely interpretation of this finding is that forward linkages of service sectors into GVCs are associated with significant outsourcing of their inputs internationally.

For example, services firms tend to offshore a significant portion of their inputs overseas. This can be observed in financial services, where financial firms tend to outsource their data management or specialised tasks. Another example is the outsourcing of basic design tasks in architectural services (Heuser and Matto 2017).

Therefore, higher forward linkages might be associated with significant losses in jobs. Finally, the study does not find a significant association between GVC-related variables and employment for agricultural sectors.

Spillover effects of GVC-related variables on employment

My study also suggests that job creation is susceptible to significant effects that arise as a result of the cross-industry input-output interconnectedness, which is captured via the input-output weight matrix concept (Mohamedou, 2019).

The indirect effects are mainly observed for the manufacturing sectors in which high backward and forward linkages in one sector deteriorate employment formation in sectors connected to it via the input-output weight matrix.

A plausible explanation is labour mobility. This suggests a relocation pattern is observed among workers towards sectors with higher participation in GVCs and thus higher productivity and incomes, which leads to a declining number of employees in the sectors.

Overall, my research sheds light on the importance of participation in GVCs through backward and forward linkages for the job creation process at the sector level in Turkey. There are significant associations between GVC participation and employment, as well as spillover effects. It is important for policy-makers to understand the mechanisms through which these spillovers effects take place.

Further reading

Baldwin, Richard, and Anthony J Venables (2013) ‘Spiders and snakes: offshoring and agglomeration in the global economy’, Journal of International Economics 90(2): 245-54.

Balsvik R (2011) ‘Is Labor Mobility a Channel for Spillovers from Multinationals? Evidence from Norwegian Manufacturing’, Review of Economics and Statistics 93: 285-97

Banga, Karishma (2016) ‘Impact of Global Value Chains on Employment in India’, Journal of Economic Integration 31(3): 631-73

Feenstra, RC, and GH Hanson (1996) ‘Globalization, Outsourcing, and Wage Inequality’, American Economic Review 86(2): 240-45.

Grossman, Gene M, and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg (2008) ‘Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring’, American Economic Review 98(5): 1978-97.

Heuser, C, and A Matto (2017) ‘Services trade and global value chains’, in ‘Measuring and analyzing the impact of GVCs on economic development’, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Kummritz, V (2016) ‘Do Global Value Chains Cause Industrial Development?’, CTEI Working Paper No. 2016-01.

Mohamedou, ND, and Tengku, MC (2021) ‘Impact of Backward Linkages and Domestic Contents of Exports on Labor Productivity and Employment: Evidence from Japanese Industrial Data’, Journal of Economic Integration 36(4): 607-25.

Mohamedou, ND (2019) ‘Impact of Global Value Chains’ Participation on Employment in Turkey and Spillovers Effects’, Journal of Economic Integration 34(2): 308-26.

Mohamedou, ND (2020) ‘Inter-Industry Spillovers in Labor Productivity and Global Value Chain Impacts: Evidence from Turkey’, ERF Working Paper No. 1430.